In my last two articles, I started discussions about lower limb function. Having written about the superficial and deep flexor tendons, I believe it would be a mistake not to bring the suspensory ligament (SL) into this series.

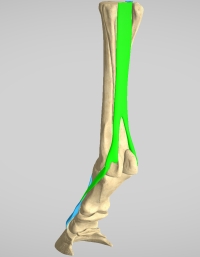

Hoofexplorer.com photo

Figure 1: The suspensory ligament (green structure) begins at the proximal (uppermost) end of the cannon bone. It then extends distally (downward) along the back of the cannon bone and between the splint bones. Approximately where the splint bones end, the SL divides (bifurcates) and attaches to the sesamoid bones.

The SL works hand in hand with those flexor tendons in terms of support and propulsion of any performance horse. It is also the largest ligament in the lower leg. The suspensory ligament in Fig. 1 (green structure) begins at the proximal (uppermost) end of the cannon bone. It then extends distally (downward) along the back of the cannon bone and between the splint bones. Approximately where the splint bones end, the SL divides (bifurcates) and attaches to the sesamoid bones. This attachment is so strong that severe SL strains can actually affect these sesamoid bones.

The branches of the SL then extend down and around the long pastern, joining the common extensor tendon (blue structure in Fig. 1) where they extend distally to the attachment on the extensor process of the coffin bone (Fig. 2). This attachment on the coffin bone means that anything which flexes the coffin joint downward puts more stress on those SL branches below the sesamoids.

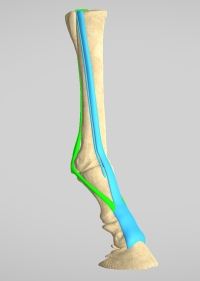

Hoofexplorer.com photo

Figure 2: The branches of the suspensory ligament (green structure) extend down and around the long pastern, joining the common extensor tendon (blue structure) where they extend distally to the attachment on the extensor process of the coffin bone.

Fig. 3 is from Mitch Taylor, owner of the Kentucky Horseshoeing School. This picture is a terrific illustration of the stress placed on those SL branches while the leg is at peak loading within a stride. Imagine what a higher hoof angle would do to those ligaments in this moment.

“The main function of the suspensory ligament is to support and prevent oversettling or hyperflexion of the fetlock,” wrote Doug Butler in Principles of Horseshoeing. “The suspensory ligament relieves stress on the flexor tendons. It absorbs concussion and gives impulsion or spring to flexor tendon movements.”

Suspensory ligaments are not the same size structure on the front and back legs. The front SL is broader and more oval-shaped. It is also a larger structure. The hind SL is rounder and slightly less massive. In her presentation at the 2016 International Hoof Care Summit, Dr. Renate Weller described the hind SL as 20-25 percent smaller than its front counterpart. Taylor, who does as many dissections as anyone, believes that the smaller space between the two splint bones of a hind leg may dictate the difference to some degree. He also adds that while the hind SL is less wide and more round than the front SL, it is slightly deeper front to back.

Photo courtesy Mitch Taylor

Figure 3: The branches of the suspensory ligament (green structure) extend down and around the long pastern, joining the common extensor tendon (blue structure) where they extend distally to the attachment on the extensor process of the coffin bone.

Injuries to the SL can vary. There may be upper suspensory involvement, which occurs above the sesamoid bones in the main body of the SL sometimes referred to as the interosseus muscle. Other injuries are unilateral (one side) or bilateral (both sides) of the extensor branches below the sesamoids. Dr. Vern Dryden, an excellent equine podiatrist formerly from the Rood and Riddle Veterinary Clinic in Lexington, Ky., believes that most extensor branch injuries behind are bilateral where fronts can be either bilateral or unilateral. Dryden added that the pivot, turn, and change of direction opens the door for unilateral extensor branch injuries of the front leg. This situation is, of course, not normally applicable to most racing situations unless they are jumping shadows, avoiding accidents, or being turned sideways for some unknown reason. In racehorses, hind SL injuries are the most common.

When shoeing a horse with SL damage (desmitis), never raise the hoof angle. Look at Fig. 3. It is obvious what a higher heel, or buried toe, would do to those extensor branches that are maximally stretched and then, to a lesser effect, the interosseous muscle above the sesamoids. Lowering hoof angle can ease tension on the SL, but increases stress on the flexor tendons. Dryden suggests extended heels can be helpful depending on the location of the injury within the suspensory structure and recommends not extending the shoe beyond the bulbs of the heels.

Any time the toe sinks deeper into the ground than the heel, that downward rotation increases the tension on the SL. Be careful with the type of shoe used in soft footing. Toe grabs, said Taylor, can actually facilitate this downward rotation of the toe during the slide phase of the stride by plowing deeper into the surface as the hoof slides forward while loading. I personally find this idea very interesting. Having never liked big toe grabs to begin with, I believe there is a safer way to have effective traction for the hind limb.

Dr. Jean-Marie Denoix has developed a series of horseshoes with the basic idea of floating the toe or affected branch via widening the web of that shoe in those areas so that the widened section of shoe will not sink into the footing as much, thus reducing tension on the affected part of the SL.

The SL is quite possibly affected by shoeing more than any other structure in the lower limb. Having a basic idea of what that structure is doing and how shoeing affects it can help to alleviate a bit of the suspense in the suspensories.

Veteran Standardbred farrier Steve Stanley of Lexington, Ky., authors a monthly column for Hoof Beats, the official harness racing publication of the U.S. Trotting Association. The American Farriers Journal Editorial Advisory Board member offers plenty of practical advice that will be of special interest regardless of the type of horses that you work with. Click here to read more from Steve Stanley's Hoof Beats series.

Post a comment

Report Abusive Comment