David Woodward forged and shaped many a horseshoe during his more than 30 years as a farrier. But now the strong hands and arms that once hammered and bent iron and steel to fit and support the hooves of galloping horses are being used to delicately manipulate gold, silver and other precious metals into horseshoe-themed jewelry for the horse set — and hopefully to help Woodward forge a new career following a devastating injury that ended his shoeing career.

“Shoeing horses was something that I loved,” he says. “It was never hard to go to work when the work was shoeing horses.”

So it’s not surprising that as Woodward begins rebuilding his life, he’s exploring career paths that enable him to retain ties with horses. They’re his passion and something he’s been around “pretty much all of my life.”

Building A Good Life

Woodward actually built two shoeing careers. The first was in his native Connecticut, following his graduation from Bud Beason’s Oklahoma Farrier’s College during the early 1970s. He built a good practice, shoeing horses in Connecticut as well as in neighboring New York and Massachusetts. Then in 1989, he and his wife, Ann, took a vacation trip to the area around Southern Pines, N.C.

“We were here for 3 days and we bought our farm,” he says, smiling at the memory. “It took us a couple of years to actually get moved down here, but we fell in love with the area right away.”

DETERMINED AND UNDETERRED. David Woodward still is able to mow the grass at his North Carolina farm. With the help of an old friend, Bobby Worden of Morris, Conn., a hoist was designed and rigged on his tractor. With the help of his wife, Ann, he can get onto the tractor and operate it.

Like any shoer in a new area, Woodward worked hard to build his business. He took shoeing work at a local racetrack to help him get started. He says he was just starting to pick up some accounts when he suffered a broken leg while shoeing a Thoroughbred. He was off work for 6 months while recuperating.

“I pretty much had to start all over,” he says.

But he was determined. He looked for opportunities to help clients along Youngs Road, a well-known North Carolina horse area, where higher performance horses — and consequently higher-paying owners — could be found.

“Once I got my foot in the door, I made sure I stayed,” he says.

As 2000 dawned, life was good for the Woodwards. Dave had a thriving shoeing practice, doing work he loved. Ann was running a small Western-wear shop and their dream home near Southern Pines, N.C., was shaping up the way they’d always hoped.

A Good Life, Interrupted

That all changed on the night of Jan. 20. Ann was away for a few days on a business trip. Dave had gone out to the barn to take care of their horses. But he lost his balance while working in the haymow and plunged 15 feet into a stall, fracturing his neck in three places and breaking his back in two more.

He lay bleeding on the floor, unable to move. He fought to remain conscious, fearful of freezing to death. Somehow he made it through the night and was discovered the next morning by Joey White, his shoeing apprentice, who called an ambulance. Emergency personnel told him later than his body temperature was just 82 degrees when he was found.

HORESHOE BUCKLES. David Woodward displays some of the brass belt buckles he’s made. Since an injury left him unable to shoe, Woodward has explored other careers, that let him take advantage of the tool skills and knowledge he developed during more than 30 years as a farrier.

Dave lived, but he’s been paralyzed from the chest down ever since. He’s in constant pain and he spends his waking hours confined to a wheelchair.

A lot of people who have been through what Woodward has would have been ready to give up. Woodward says giving up may have crossed his mind, but he never let the thought actually take up residence. Ann doesn’t really seem surprised about the way her husband reacted to his injury.

“I think that’s something people can learn from Dave,” she says. “Just because something like this happens to you, it doesn’t mean you can’t go on. You may not be able to go on the same way, but you can go on.”

Ann has kept going on as well. She’s kept the store running and expanded her efforts. She’s been there through the operations and the rehabilitations.

“When you love each other, you’re there for each other through the good times and the bad,” she says simply.

The first years after the accident were tough ones. He had medical insurance at the time of the accident, but his benefits ran out over the course of five operations he had before he regained the use of both arms. Today, he can use his arms to propel his wheelchair. He drives a specially equipped van and has even managed to come up with mechanical hoist that enables him — with Ann’s help — to get into the seat of his tractor so that he can mow the farm’s 20 acres.

Rebuilding A Life

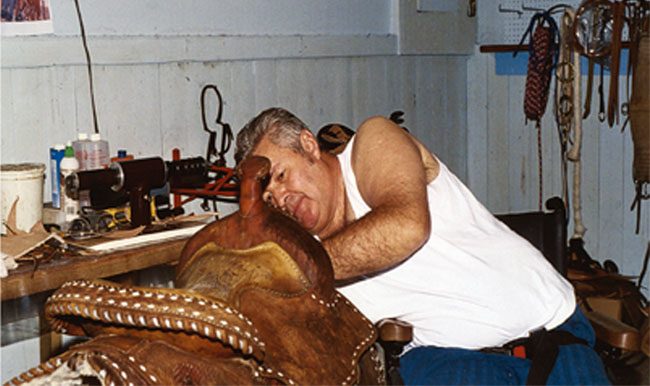

As he regained at least some mobility, he began working again. Donald Jones, a friend and colleague from Pleasant Garden, N.C., built him a custom-made anvil and stand that Woodward could work at while seated in his wheelchair. He opened a leather shop in a workshop in the same building that housed Ann’s shop, which she had expanded to include farrier supplies. He also started making horseshoe belt buckles, a first step on the way to jewelry making.

The first buckles were made from stainless steel. Jones started selling them through NC Tool and Ann offers them in her shop as well. Woodward eventually sent some of the models of the buckles to a firm in Washington State, which copied the buckles and made them available in brass. Woodward plans on coming out with a new style each year.

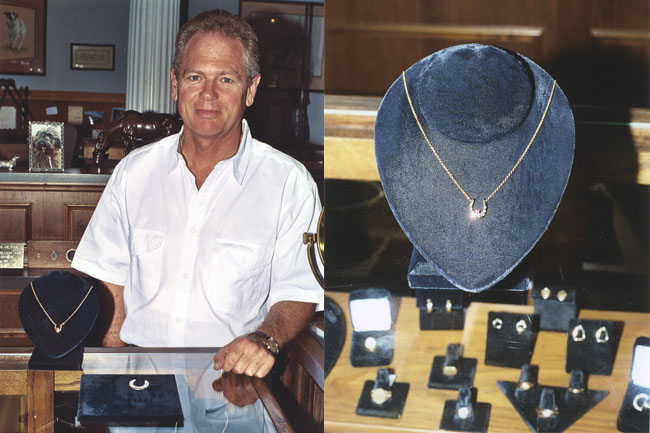

JEWLRY COLLABORATER. Mark Hawkins displays a pendent and sliver belt buckle he and David Woodward made together. Hawkins, a partner in Hawkins and Harkness Jewelry in Southern Pines, N.C., has been a mentor for Woodward in his jewelry-making efforts.

With the help of Mark Hawkins, a jeweler whose shop, Hawkins and Harkness Jewelry, is located in Southern Pines, Woodward has started designing and making horseshoe-themed jewelry.

One of his first big projects was a ring that a Virginia woman asked him to make for her husband, a lifelong horseman. Woodward carved a form in wax, which included a horseshoe on the face of the ring. Hawkins made a mold from the form and poured the gold for the ring into it. Woodward then cut the gold away from the inside of the horseshoe so that Hawkins could mount a turquoise stone inside the shoe. Hawkins welded the stone in place and Woodward finished the ring — with the same care he once used for finishing hooves on show horses — “buffing it up and making it pretty” for the final product.

“It was really a well-made ring and it sold for about $900,’” he says.

Jewelry making involves many of the same skills and similar tools that he used as a farrier — knowledge of bending and shaping metal, using a hammer, tongs and heat — but it is at a much finer level, he says. It’s challenging work that he enjoys. He hopes to eventually have a line of horseshoe-themed pendants, earrings and other forms of jewelry that Ann can sell at the tack shop.

He and Hawkins, who acts as a collaborator and a mentor, recently completed a horseshoe pendent with small gems set in the web. Hawkins has also encouraged him to turn out his belt buckles as well as other horseshoe-themed jewelry in silver, as he believes it would be more saleable as well as easier to work in than steel.

Hawkins does believe there could be a market for the jewelry the two of them are making in this area of horse enthusiasts.

“Horse people are quirky,” says Hawkins, who is a horseperson himself. “If they see something like this they like, they’ll buy it.”

Saddling Up

Woodward’s leather repair business also helps keep him busy. Although he had never actually worked with leather before his injury, he did have an extensive knowledge of saddles and knew how to use tools. He’s reconditioned old saddles and replaced leathers and straps on new ones. While he’s worked primarily with riding tack, he’s also been involved in other leatherwork.

He’s made up some shoeing aprons for farriers and also patched and repaired worn ones. He’s made custom leather coverings ordered by people for their boats. He also designed and made a pair of quick-release harnesses for dogs that local Army Reserve K-9 units were taking along to Iraq.

He’s at his shop Monday through Saturday for at least a few hours each day. There are days, though, when he has to either limit his hours or take the day off.

“Sometimes I’m just so eaten up with pain that I can’t concentrate on my work,” he says.

Pain is something he’s learned to live with. It’s a constant companion, 24 hours a day, he says. He had tried many kinds of therapy and says he had recently gained some relief through acupuncture.

He and Ann have also explored the possibility of experimental stem-cell operations being offered overseas. They believe such therapy offers at least some hope for David to regain more movement and feeling.

A Shoeing Mentor

Although he’s not able to shoe horses himself anymore, it’s clear that his love of the craft is still deep.

“When I was at school, we’d fire up the forges at 6 or 7 in the morning,” he fondly recalls. “We’d work in the forge until 10 or 11 o’clock, then go out on a trip to shoe horses. I thought it was an excellent school and I really got a lot out of it.”

RING BEGINNINGS. David Woodward designed and cut this form in wax as the first step in making a gold ring with a turquoise stone set inside the horseshoe.

A huge shoe board still hangs on the wall of his shop in Lakeview. It’s covered with shoes and braces he forged while going to school in Oklahoma. He also says he learned a lot from shoeing another type of animal in his native New England.

“When I started, I shod a lot of oxen,” he says. “Most of them were used in pulling competitions. I’d actually say that shoeing oxen made me a better horseshoer.”

Woodward still has an ox shoe hanging on his shoe board. A single “shoe” for an ox actually comes in two separate halves, each one fitted to a side of the animal’s cloven hoof.

“Shoeing oxen teaches you to be very good at leveling shoes and making nails count,” he says. “Because you can only nail to the hoof wall.”

Throughout his shoeing career, Woodward has worked on a wide variety of breeds and types of horses that were used in many different disciplines. In the years just before his accident that ended his horseshoeing career, he’d been focusing more and more on shoeing driving horses.

“I was shoeing a lot of the driving horses that were down here practicing for the Olympics,” he says.

Woodward has trained a lot of apprentices during his career. It still makes his day when another farrier will stop by his shop or call him on the phone to ask his advice on shoeing this horse or on shaping a particular shoe. He may not be able to shoe horses himself anymore, but he still possesses a wealth of knowledge, tempered with years of experience. But he says the best advice he can offer young shoers is relatively simple.

“Always do your very best, even if it takes you all day to do it,” he says. “I told all the guys who worked with me that I didn’t care how long it took them to do the job, so long as they did the job right.”

Post a comment

Report Abusive Comment