How many horses in your practice battle palmar foot pain, riding that razor edge between working soundness and days off? Pain originating in the palmar or rearward section of the foot isn’t a very specific diagnosis, but it certainly affects a lot of horses — and thereby a lot of farriers.

And you aren’t alone — veterinarians are often called in to help diagnose the exact cause of palmar foot pain as well. In an effort to improve success rates with these often-difficult cases, the American Association of Equine Practitioners (AAEP) held a full afternoon of presentations on palmar foot pain during its 2006 annual convention (held during December in San Antonio, Texas). Following is a report of that session, which included presentations on palmar foot function, diagnosis of problems, treatment options, and shoeing options. Presenters included:

- Stephen O’Grady, DVM, MRCVS, member of the International Equine Veterinarians Hall Of Fame and owner of Northern Virginia Equine in Marshall, Va.

- Andrew Parks, MA, VetMB, MRCVS, Dipl. ACVS, member of the International Equine Veterinarians Hall Of Fame, professor of large animal surgery and head of the department of large animal medicine at the University of Georgia.

- Kent Carter, DVM, MS, Dipl. ACVIM, professor of internal medicine and a lameness clinician at Texas A&M University.

- Robert Hunt, DVM, MS, Dipl. ACVS, of Hagyard Equine Medical Institute in Lexington, Ky.

Understanding The Palmar Foot

Parks presented a detailed anatomical review of the palmar foot with state-of-the-art computerized imagery from the Glass Horse project www.3dglasshorse.com, and also discussed functional anatomy of the palmar foot.

“The evidence from several studies suggests that the principal function of the heels is to dissipate energy during the impact phase of the stride,” he said. Effective energy dissipation means that forces on the outside of the hoof capsule are translated to internal structures, which in turn shift, stretch or compress to absorb the shock so it doesn’t damage any part of the hoof or limb. If any internal structure can’t handle the stress, damage and pain result.

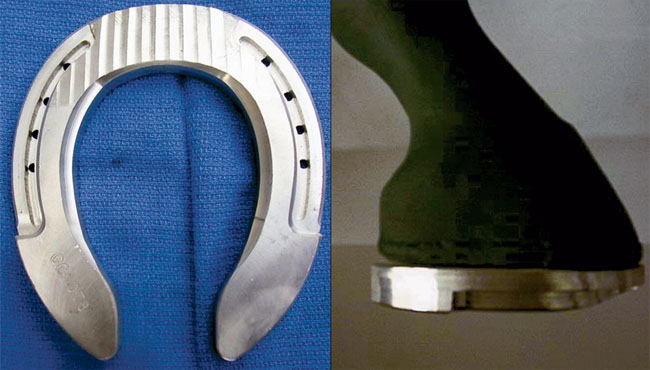

BACKING UP BREAKOVER. This aluminum shoe has the breakover moved palmarly toward the heels.

The majority of energy dissipation associated with impact is absorbed between the hoof and the distal phalanx, through a variety of mechanisms including hoof expansion, said Parks.

“Hoof expansion maximizes about 30 percent into the stride, a little longer than vibrations from impact last,” he reported. “At around 75 percent of the stride, expansion is stable, and at about 85 percent of stride, the heel comes off the ground and the quarters come in a bit.”

Two Views On Heel Expansion

How does hoof expansion work? There are two traditional explanations. “One is that frog pressure pushes on the digital cushion, which expands outward,” Parks said. “The second theory says that middle or second phalanx descent (with weight bearing) compresses the digital cushion, also expanding the hoof.

“But three functional studies show somewhat conflicting results. One suggests that there is no direct relation between frog pressure and foot expansion. Another study suggests that pressure within the frog may actually decrease with foot expansion. The third study indicates that there is a relationship between increased frog pressure and hoof expansion. Additionally, an anatomic study, which examined the structure of the frog, digital cushion and associated venous plexuses provides a hypothesis for a hemodynamic mechanism for dissipating shock (blood pushed out of the foot during loading allows room for structures to shift and dissipate energy).

“Any conformation or imbalance that impairs this natural function is likely to result in disease, because the majority of lameness associated with the heels is related to stress-induced injuries,” Parks stated.

Often A Sneaky Problem

While palmar foot pain can certainly originate from an acute injury, it often has its roots in poor foot conformation that gradually compromises foot health.

“Injury may occur in any horse if the insult is severe enough, but if there is an anatomical predisposition because of abnormal balance or conformation, or a farriery manipulation that focuses stress, then injuries will be more likely to occur at submaximal work,” commented Parks.

O’Grady explained that in many horses, palmar foot pain can be attributed to continuous repetitive overload of the frog, digital cushion and heel base (consisting of the hoof wall, buttress, angle of the sole and the bars) over time.

Whether this is the result of genetically weak feet, unsuitable conditions when the horse was young that prevented the soft tissue structures from maturing or improper hoof care that allowed the heel to grow forward, the result is the same. Instead of the foot being upright and strong, the heels are pulled forward and crushed — and the digital cushion along with them.

Generally, this problem begins with toes that are allowed to grow too long, which throws a greater portion of the horse’s weight onto his heels. The hoof wall is thinner at the heels, said O’Grady, making it more flexible. “This increased flexibility is what allows the normal physiology of the foot in the form of expansion to take place, but in turn, it makes the heels more vulnerable to damage,” he noted.

When the heels are overloaded, they all but stop growing, while the toe continues to grow normally, he explained. This causes the heel angle to gradually get lower and lower until the heels are nearly parallel to the ground and often roll under. This displaces the heels, causing them to roll under and put pressure on the bars; as this occurs, the heels have collapsed and begin to contract.

Now that the heels are all but gone, the palmar foot is no longer able to accept load during weight bearing, so additional stress is placed on internal structures — i.e., soft tissue structures. With no heels, the weight-bearing job falls to the frog, digital cushion and deep digital flexor tendon. They weren’t designed for that; they can’t dissipate the shock of landing effectively without healthy heels. Damage, pain and lameness often result.

“Seldom does one have a case of palmar foot pain without primary or secondary hoof distortion, which might be irreversible,” O’Grady noted.

Diagnosing The Cause Of Palmar Foot Pain

The palmar foot is a complex region consisting of structures common to other parts of the body, such as bones, tendons, ligaments, blood vessels and nerves, and unique structures such as the frog, navicular bone and digital cushion. Thus, evaluating this area to diagnose lameness is an art, and not yet a science.

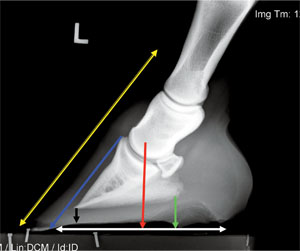

HOOF-PASTERN AXIS. This lateral radiograph illustrates the hoof-pastern axis, center of articulation, sole depth, palmar angle of the distal phalanx, breakover and placement of the shoe. A good set of radiographs is essential for any therapeutic shoeing.

“Evaluation of a horse presented for palmar foot pain is like playing Wheel of Fortune —sometimes you guess it with two out of 10 letters, but some will take nine out of 10,” Hunt commented. “Don’t get in a rush with the evaluation, and remember that there are no absolutes. Some horses may take multiple sessions to arrive at a diagnosis; it can get very costly.”

Hunt suggested a three-fold approach, as follows:

- Take a complete history.

- Complete a thorough physical examination.

- Observe the horse’s gait.

“Try to look at the horse at rest and study him while talking to the owner,” Hunt suggested. “Horses tend to assume a particular stance that can tell you a lot. Have them walk straight, in circles, on an incline and after flexion. For many horses with navicular pain, the common complaint is that they’re getting rough, choppy and/or short-strided going downhill. Usually that’s the first thing to go. You might need to watch them jog or canter with a rider to precipitate some of the problems.

“Clinically we think they have a reduced cranial (forward) phase of the stride because they try to land more on their toes,” he said. “They may unload the (sore) feet, or they may just be rough and choppy, especially if the problem is bilateral (in both front or hind limbs).”

Next, if a veterinarian is involved with the case, comes diagnostic anesthesia —nerve blocks — to try to isolate the pain to a particular region of the foot. “For years, we learned these things were fairly straightforward. That’s not necessarily true,” said Hunt. “Findings are not necessarily consistent. To maximize information from diagnostic anesthesia, several sessions of performing blocks may be required, and the sequence may be determined on an individual case basis.”

Diagnostic imaging guided by physical examination findings is often the last step. Hunt noted that radiographs, ultrasound, nuclear scintigraphy and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) all have a place in evaluating palmar foot pain.

“Every foot needs a radiograph!” Hunt stated emphatically. “I’m a big proponent of following horses and monitoring them, and this provides a world of information to save you. It’s like getting all the vowels in Wheel of Fortune — you might get it right then.

“MRI is the new gold standard of diagnosis and a hot topic of discussion in many meeting sessions, but I think we’re still low, low on the learning curve, he added. There are many false positives and we still don’t have the ability to age these lesions (determine how long they’ve been there). There are usually multiple areas of involvement; deciding which one is most relevant will fall back on us. We have to correlate what we see with the clinical picture.

“As with other aspects of medicine, a joint effort of several diagnostic aids is required to obtain as specific a diagnosis as possible,” he concluded.

Treating Palmar Foot Pain

“There are many therapies for palmar foot pain. When there’s a whole bunch, it’s because none of them work, or there’d only be one!” commented Carter. “But there are a whole bunch of therapies because palmar foot pain is caused by a whole lot of different problems.”

He discussed case selection and treatment of palmar foot pain, noting that a reasonable diagnosis is key. “But you don’t always have one,” he said. “Sometimes you have a presumed diagnosis, and sometimes a wild guess. We need to locate the pain — the source of lameness — so we know what we’re treating.

CENTER OF THE FOOT. A solar view of the hoof with a line drawn across the widest part of the foot and corresponding lines drawn to the toe and the heel. According to Dr. Steven O’Grady, the widest part of the frog should be used as a guideline in shoeing and trimming to make sure the foot in under the center of articulation of the coffin joint.

“Different etiologies (causes of pain) mean different therapies,” he went on. “For example, subsolar/frog bruising, navicular disease and distal deep flexor tendonitis have similar lameness examination findings and response to diagnostic analgesia, but each would warrant a different therapeutic approach.”

Carter discussed the following treatment options for horses with palmar foot pain:

- Corrective/correct shoeing — “In every lameness originating from the foot, the role of shoeing and hoof balance should be considered in the etiology and possible therapy of the lameness,” he said (more on shoeing later in this article).

- Synovial (joint) injections — Carter said these are used when you diagnose or suspect a problem that may respond, or as a therapeutic trial. Options include hyaluronate or hyaluronic acid (HA, to improve joint lubrication), corticosteroids (to reduce inflammation), antibiotics and interleukin-1 receptor antagonist protein to reduce inflammation and promote healing.

- Intralesional tendon injections — This recent approach to therapy consists of using computed tomography, radiography, fluoroscopy, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or ultrasound to guide injection of stem cells, hyaluronic acid or other substances intended to speed tendon healing directly into the lesion. “This method offers promising potential to selected cases,” Carter noted.

- Systemic medications — He described pros and cons of many medications, including isoxsuprine, tiludronate, intravenous HA, intramuscular polysulfated glycosaminoglycans (PSGAG) and systemic anti-inflammatory medications such as phenylbutazone.

- Surgery — Digital tendon sheath arthroscopy can be used to treat areas where the tendon has adhered to its sheath or to cut ligaments that are damaged or causing problems.

- Athletic rest — (controlled exercise and physical therapy) often allows healing of an injury, he noted. “Simply removing their shoes and turning them out for several months is rarely curative, and a more controlled approach to exercise and return to use is preferable in conjunction with other therapies,” he said.

- Shock wave therapy — Carter noted that this option has reportedly good results for tendon injuries, but he has not seen good results for navicular problems.

- Oral nutraceuticals — Carter noted that while some owners report success with oral nutraceutical supplements designed to improve joint health, others do not. He also reported that one study found that while chondroitin sulfate (a common ingredient in these products) was absorbed into the bloodstream of study horses, glucosamine (another common ingredient) was not.

- Neurectomy — “Palmar digital neurectomy (cutting the palmar digital nerve) is a reasonable option to get more use out of a horse when other things don’t work,” he said. “You have to have the right cases and the right owners. Horses that are crippled and get just a little better with a nerve block are not the best cases.”

Complications can include nerve regrowth (with returning lameness), neuroma (a painful tumor at the end of the cut nerve), deep digital flexor tendonitis and possibly rupture, he added.

“Many cases require a combination of corrective trimming and shoeing, intrasynovial medications and controlled exercise/athletic rest regimes,” he concluded. “And remember that replacement therapy is a viable option for some horses.”

Shoeing Options

“Podiatry generally will form part or all of the treatment for foot pain,” said O’Grady. “Our approach to therapeutic shoeing should address three parameters: The visual structures of the hoof complex, the function of the distal interphalangeal (coffin) joint and the areas of pathology confirmed through diagnostics and imaging.” The degree of improvement depends on what structures are damaged and how much, how long the problem has been present, its ability to heal and how much its dysfunction stresses adjacent structures, he noted.

He recommended the following trimming/shoeing guidelines:

- The foot should be trimmed to align the hoof/pastern axis as closely as possible.

- The widest part of the foot is used as a guideline so the foot is under the center of articulation of the coffin joint.

- The heels should be trimmed to or toward the base of the frog if possible.

- Breakover should be moved back to decrease the moment arm (leverage) on the coffin joint and the pressure placed on the dorsal hoof wall.

- Very little sole should be removed.

- F Any shoe should have a wide web, be as light as possible, have good nail placement, use as few nails as possible and use the smallest nails possible to minimize trauma to the damaged foot.

O’Grady and Parks discussed the effects of several aspects of foot and shoe manipulations, and management practices, on horses with palmar foot pain.

“Steel shoes attached with nails are known to diminish the natural (shock) dampening mechanisms of the distal limb compared with unshod feet,” reported Parks. “Specifically, shoeing with plain steel shoes increases the frequency and amplitude (degree) of the oscillations in the ground-reaction force (exerted on the foot by the ground) during the impact phase of the stride and decreases the expansion of the quarters and heels during the stance phase. But certain plastic shoes used with synthetic viscoelastic pads reduce both the frequency and magnitude of the vibrations associated with the foot’s impact with the ground.

GLUE-ON OPTION. This glue-on shoe has heel elevation designed into the package. Glue-ons also involve less trauma to a sore foot than nailing.

“Additionally, finite element analysis suggests that the nails, particularly those placed most palmarly (rearward) in the foot, cause concentration of stress in the wall,” he noted. “This would seem to be an inescapable consequence of nailing on shoes, and is a good reason why the nails should not be put in the rear half of the foot.”

Breakover — We can take some lessons from athletic footwear for humans, said O’Grady. “Look at the breakover in this running shoe,” he told the audience, showing a photo of a running shoe with the toe rolled up off the ground and the heel of the shoe wide and elevated. “It’s good for horses too, to move breakover further toward the heels and have elevation of the heels built into the shoe.”

Heel elevation — “This practice changes joint angles, places more pressure on the dorsal (forward) aspect of joints between the second and third phalanges (the distal interphalangeal joint), decreases heel growth and decreases deep digital flexor tendon tension,” said Parks. “In motion, elevating the heels increases the likelihood of heel-first contact and causes the distal phalanx to roll forward more after first contact before the foot becomes in stable contact with the ground. During the second half of the stance phase of the stride, elevating the heels delays the movement of the center of pressure to the toe at breakover and thus, their unloading.”

Raising the heels with a wedge pad is common, but it is often harmful to place a wedge pad across already compromised heels, said O’Grady.

He noted that the best way to raise heels in these horses is by using a shoe that has some heel elevation built in and has the breakover point (the forward-most point where the shoe’s ground surface touches the ground on a hard surface) moved palmarly (back toward the heels).

This can be easily accomplished with a grinder. This decreases the shoe’s leverage on the heels and avoids damaging them further, while reducing stress on damaged internal structures. Adding impression material or similar soft deformable material to the sole can increase ground surface area on the bottom of the foot, disperse the load more evenly and further cushion the internal structures during impact, he added.

Medial/lateral wedges — If a problem exists in only one side of the palmar foot, one might consider a medial or lateral wedge to lift that area. But that might not be such a good idea. Parks explained, “The dynamic effects of mediolateral wedges are that they move the landing pattern of the hoof and its center of pressure to the higher side.”

Research suggests that a horse will try to land each foot with the coffin bone flat (parallel to the ground), but if he’s wearing a medial or lateral wedge, the high-wedged side of the foot strikes the ground first because his coffin bone is “flat.” The horse doesn’t realize that the hoof and wedge make that side of his foot longer.

“So perhaps we should think of a wedge as not only raising one side of the foot when it is on the ground, but also as extending or lengthening that side of the hoof wall when the foot is in the flight phase of the stride,” he summarized.

Extended-heel and bar shoes — “Studies have primarily examined the effect of egg bar shoes when the horse is standing or moving on a firm, flat surface,” said Parks. “At rest, they move the center of pressure palmarly in relation to the toe; this is considered beneficial for the deep digital flexor tendon and navicular bone but is potentially harmful to the hoof capsule at the heels.”

Bar shoes can be used without damaging the heels, but O’Grady said he prefers straight bar shoes rather than egg bar shoes. Egg bar shoes are often fitted so they extend beyond the heels, thus creating leverage on the already damaged heels, he commented.

Composites/adhesives — Acrylics can be used to rebuild and raise the heels, protect them from further wear, increase mass of the heels so they can be loaded and extend the ground surface of the foot, O’Grady noted. Glue-on shoes can be helpful because they prevent the wear of the heels against the shoe and can be attached without nailing to a sore foot.

Ground surface — “It makes no sense to take a horse with palmar foot pain and work him on a hard surface,” O’Grady stated emphatically. He noted that soft ground surfaces (such as sand) allow the sole and frog to bear some weight, giving the hoof wall a break. They also allow the toe to rotate into the ground, reducing the strain breakover places on tendons, ligaments, and the navicular bone.

Rest — “It’s prudent to think that if the hoof capsule and soft tissue structures are compromised, the horse needs time to recover,” O’Grady said.

It Takes Two

“Podiatry is the only aspect of equine veterinary medicine that requires input from two professionals” — the veterinarian and the farrier, said O’Grady. “A working knowledge of the form and function of the equine foot is essential for equine practitioners and farriers to formulate a shoeing plan and implement the appropriate hoof mechanics.

“The anatomical and medical knowledge of the veterinarian, when combined with the mechanical and technical skills of the farrier, provides a comprehensive team that can only enhance the management of palmar foot pain.”

Post a comment

Report Abusive Comment