J.D. Downs shapes a shoe at a ranch along the Colorado Front Range. The farrier from Frederick, Colo., north of Denver, says shoeing in the high, dry climate means dealing with hard, dry feet.

Late spring is a beautiful time of year along the Colorado Front Range, an hour or so north of Denver. It seems as if there are horses in almost every field along the highway and plenty of billboards advertising rodeos and horse shows.

It looks like a good place to be a farrier and do some Shoeing For A Living.

One such farrier is James “J.D.” Downs. The Frederick, Colo., shoer is starting this particular Shoeing For A Living Day by getting a second opinion — and it’s one that doesn’t cost his client a dime.

Downs meets his mentor, and still once-a-week shoeing partner Neil Miller, for breakfast before heading out to his first call. Downs wants to get Miller’s input on a horse he’ll be shoeing that day.

Downs has been shoeing full time since 2006. He was originally a schoolteacher, but completed the horseshoeing program at Colorado State University in Fort Collins, Colo., taught by Steve Mellin. Downs figured that horseshoeing might make a good part-time and summer job, but as things have worked out, it’s become his primary employment.

Downs’s practice includes a lot of reining horses, but the one he wants Miller to look at with him is a hunter. The trainer — a regular client of Downs — has asked him to look at the horse after it developed some problems.

Downs hasn’t shod this particular mare before. He’s been told that the horse was moving well when shod with steel bar shoes and pads. But when a change was made to open-heeled aluminum shoes, her movement hadn’t been what the trainer wanted. Still, she didn’t want the horse to go back to the steel bar shoes because of the added weight.

9:30 a.m. When they arrive, Miller and Downs look over the horse together. They agree that, possibly due to the removal of the bar shoes, the horse is back on her heels a bit. Downs thinks that in the softer dirt of the arena, the heels may be sinking in more than they were with the bar shoe. He thinks this could cause some tendon stretching, resulting in mild lameness.

Neil Miller hands J.D. Downs a shoe and pad combination. Miller, a shoer with over 35 years of experience, is one of Downs’s mentors. Downs asked him to join him for his first horse of the day to give him some advice. The horse, a hunter, had some navicular issues.

They both believe that adding 2-degree bar wedge pads to aluminum bar shoes will help correct the pastern angles, and still save weight over the steel bar shoes.

Miller’s second opinion basically confirmed the approach Downs was already considering, but he says he’s still glad he asked Miller to look at the horse.

“I really think it’s important not to make the mistake of thinking you’re all alone out there,” he explains. “You don’t want to get in over your head. Get help when you need it.”

Downs apprenticed with Miller and the two still shoe together at least one day a week. They also cover for one another when one is away, or when a shoe needs to be tacked back on.

Miller says that from the first time Downs rode with him, he showed a willingness to work and an eagerness to learn that has paid off for him.

“He’s earned my trust and respect,” says Miller of the younger farrier. “He’s the only guy I’ll let touch the feet of my big reining clients.”

Miller mentions that not long ago, he’d cut his hand and was unable to shoe for a few days. The reiners of one of his bigger clients were due for shoeing. Miller called the owner and told him he wouldn’t be able to do the shoeing himself, but had arranged for someone else.

“He right away asked, ‘Who’s coming?’ I told him J.D., and he relaxed. ‘That’s fine,’ he said,” recalls Miller.

9:47 a.m. Downs trims the feet and checks the shoes. He and Miller concur that the horse should be in a size larger shoe — but they also note that it isn’t going to be a matching pair.

Downs points out that one of the fronts is noticeably larger than the other. That’s something that needs to be taken into consideration in shoeing the horse.

“The smaller foot is probably going to sink into the ground differently than the larger one,” he says. “That can cause labored movement, particularly in a jumping horse.”

While Downs preps the feet, Miller trims the wedge pads, drills them out and attaches them to the shoe with copper rivets. With Miller standing by to hand him the shoes as well as the next tools he uses, the shoeing goes quickly.

Miller and Downs agreed that the horse would probably do better with wedge pads to correct its pastern angles. Miller drilled the shoe and pads while Downs trimmed the feet.

10:08 a.m. Downs finishes up the shoeing by applying Gus’s Hoof Dressing to the feet. It’s a pine-tar mixture developed and marketed by Denver, Colo., farrier Mike Joshua. The high elevation, relatively dry climate and hard ground mean Downs is usually working with hard, dry feet.

Downs points out to the trainer that the heels of the new shoes extend back more than the ones that were removed. He explains he needed the extra length to provide more support to the back of the foot, and suggests that the horse be fitted with bell boots to help keep the horse from stepping on the heels.

Following the shoeing the hunter does seem to be moving better, but Downs says they won’t know for sure until the horse has done some work. He tells the trainer to stay in touch and let him know how the horse does.

The hunter’s finished feet. Downs also extended the heels of the bar shoe past the heel buttress and recommended bell boots to help keep the horse from stepping on the heels of the shoe.

10:17 a.m. Once the horse is done, Miller and Downs part company and Downs drives toward his next stop. He mentions that the one-horse stop he just made is unusual for him.

“I like a three-horse stop,” he says. “There’s enough work to justify your set-up and tear-down time, and you can get into a rhythm. But it’s not so much work that you wear yourself out.”

He wasn’t always able to limit his work that way, he acknowledges. When he started shoeing, he had to take whatever work he could find. He does feel that by working with some good shoers, such as Miller and Craig Quinn of Castle Rock, Colo., he was able to build his practice more quickly than some novice farriers.

Still, he says that this is the first year since he started shoeing that he’s begun taking one day off a week. He’s also scheduled a vacation.

Downs will still take on new clients, but he also has some prerequisites that are another indicator of how his practice has grown. He recently turned down a prospective client who had just one horse that needed trimming. The barn was about 45 minutes from his usual area, and he didn’t have any other clients nearby. He explained to the horse owner that the stop simply didn’t make financial sense for him, and suggested she seek a farrier who was closer to her home.

10:23 a.m. Downs arrives at his next stop, GLG Performance Horses. While his shoeing book includes quite a variety of horses, as well as disciplines, he has a special affinity for reining horses. He even has a sliding plate tattoo above his right biceps.

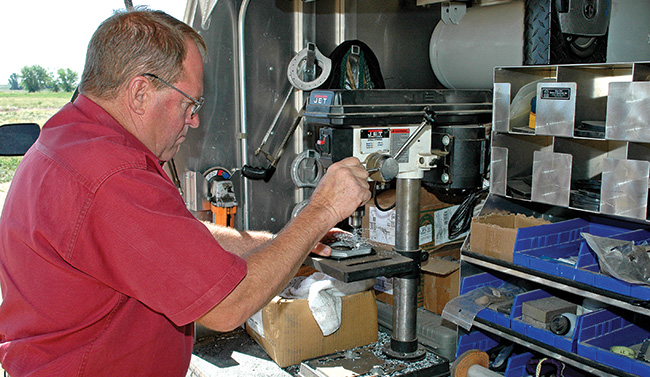

Downs touches up his hoof knife at the grinder mounted on his shoeing rig. A big part of the farrier’s shoeing book consists of reining horses — as you might expect from the reining plate tattoo.

Downs sets up his shoeing area quickly and then walks to a nearby corral, where Gabriel “Gabe” Lee Garrison, owner and trainer, is putting a reiner through its paces.

Garrison takes a brief break, remaining in the saddle, as Downs double checks his shoeing list to determine if there are any changes to it. Once they’ve conferred, Downs returns to the barn to get started, and Garrison continues his training.

10:48 a.m. First up is Lexie, a 4-year-old mare Quarter Horse, but looking at her feet, you probably wouldn’t realize it.

“Her foot is more the size of a yearling’s,” Downs explains. “I have to shoe her with a triple 0, then I have to file the shoe down”

Downs explains that he usually has a picture in his mind of what a Quarter Horse foot looks like, but says it’s important not to believe that one pattern fits all Quarter Horses. Lexie is a good example.

“She has more of a Thoroughbred foot,” says Downs of the horse. “Down in the heel and forward a little in the toe. You have to shoe her for her work as well as for her conformation.”

10:56 a.m. But her unusual foot doesn’t seem to affect Lexie’s performance. She competes at a high level.

For the most part, Downs says he doesn’t trim a reiner’s feet differently than he does any other horse. He may leave a little more sole on a reiner’s hind feet than he does on the fronts, where he wants more of a cup for improved traction.

Downs shapes a reining plate at his anvil. Downs enjoys his forging work and also competes. He won the Division 2 Live Shoeing contest at the 4 Corners Contest the weekend before these photos were taken.

His choice of front shoes will depend on the needs and action of the particular horse. With some horses, he uses aluminum shoes.

“A steel shoe may give you a little too much knee action, a little too much lift, in some cases,” he says. If an aluminum shoe is appropriate for a reiner, he likes to use Kerckhaert Triumphs.

For the hinds, Downs most often uses Anvil Brand blanks, which he then shapes and punches for nails.

“I like to punch my nail holes a little further forward than they typically are on manufactured shoes,” he explains. “By putting the nails a little more forward, I’m putting them in the strongest part of the hoof wall. I can also punch them a little coarser because of that. I think it also keeps pressure off the heels.”

Downs usually uses blank sliding plates and punches his own nail holes after shaping the shoes. He likes to keep the nail holes forward in the shoe, feeling this helps relieve pressure on the heels.

He mentions that he plans on trying Kerckhaert Pride sliding plates soon.

When possible, he prefers to use a 5 plater special nail.

11:38 a.m. Downs thinks it’s important for anyone who is interested in working with reiners to attend competitions and watch what the horses go through, as well as the differences in surfaces they compete on.

He points out that while reiners are probably best known for their spectacular sliding stops, that’s only one of the required maneuvers, all of which must be run as part of a pattern. Circles, spins, rollbacks and backups place much different stresses on the horse than the stop. A farrier has to be able to come up with a trimming and shoeing formula that enables each horse to perform at its best.

Sliding plates extend past the heels of the hinds. Downs finds that is important to line up the shoe in the direction of travel for the horse. If a horse has a tendency to toe in or out, he lines up the shoe more with the hock and direction of travel than the foot. This not only enhances movement, it helps prevent pulled shoes.

“There are a lot of things to take into consideration,” says Downs. “To shoe reiners well, you have to put in a lot of time studying. It’s important to shoe every foot with a purpose. You need to have an idea of what you want to accomplish in trimming and shoeing each foot.”

There also can be a big difference in arena footings. He mentions that after walking in an arena where an upcoming Reining Futurity will be held, he’ll probably put reiners in a thinner sliding plate, due to the hardness of the ground. The arena surface, combined with how a particular horse moves will also affect how he shapes a slider.

“A slider is a little like a snow ski,” he says. “A rounder toe will go through the snow more easily, while a narrower toe will allow you to change direction better. The same is true of slider toes and dirt.”

11:48 a.m. Downs emphasizes that, as with any shoeing, a good trim is vital.

“My first objective is to balance the foot properly, then fit the foot into the shoe,” he explains. “Particularly with a small foot like this, I want to get rid of flares and address the bull nose before I’ll nail on the slider.”

Garrison earlier told Downs he wants Lexie to be able to “skate” or “float” more in the slides, so Downs puts her in a size larger sliding plate.

12:02 p.m. As he finishes up the shoeing job, Downs points out that at first glance, the slider appears to be off center. But he says that’s deliberate.

“The slider is lined up with the direction she travels,” he explains. “It lines up with the way she toes out. That’s another thing I learned from Neil Miller.”

Downs nails on a sliding plate.

Downs does say he probably doesn’t shoe any other reiner he works on quite the same way he does Lexie, due to her unusual conformation and mismatched feet.

12:19 p.m. The next horse, an Appaloosa, has much more of the usual Quarter Horse foot. “It looks a bit like a beer can,” says Downs with a chuckle.

Downs says Garrison won the Reining Superstakes at the 2011 World Championship Appaloosa Show in Fort Worth, Texas.

While the horse does have a much more standard Quarter Horse conformation, Downs does have some factors he has to take into consideration. The horse has a relatively long pastern, so he adds 4-degree wedge pads to the fronts to help prevent bowed tendons.

A reiner, shod, tacked up and ready to go to work. At left is Gabe Garrison, owner and trainer of GLG Performance Horses, a regular client of Downs.

12:38 p.m. Downs mentions that he’s very careful about the heel checks on the hinds.

“I want a nice clean heel on the sliders,” he explains. “I don’t want to have to worry about rocks getting caught in there or debris getting trapped.

Downs explains that the direction of the “dump” of the dirt from the sliding plate helps direct the horse.

This is another horse, Downs points out, where he lines up the shoe with the direction of the horse’s movement, rather than the foot itself.

“It looks as if the shoe is a little twisted, but it’s actually the leg that’s a little twisted,” he says.

He also points out that a previous shoer had rasped the heels too much, possibly to fit the shoe, something Downs finds inadvisable.

Sliders, of course, have a lot of extended heel. Downs finds that making sure to line the shoes up with the direction of travel and the hock, instead of just the foot, helps prevent the horse from pulling the shoes.

Downs trims a draft cross at a therapeutic riding center. Downs usually leaves a little more sole on the hind feet of a reiner than he does on the front, where he wants more of a cup for traction.

“For as long as sliders are, they’re probably the shoe that I tack back on the least,” he says.

1 p.m. The final horse at GLG is a 10-year-old Morgan named Disco Kid. The horse is another top performer, having won titles at the 2011 Morgan Grand National & World Championships in Oklahoma City, Okla.

One thing Downs likes to do is make sure he runs his hands over the hoof wall before he starts trimming a foot.

“I think your hands can detect things like the beginning of flares that your eyes might not detect as soon,” he explains.

1:23 p.m. Downs shoes the Morgan’s fronts with Grand Circuit aluminum shoes. As he trims the foot, he points to rasp marks on a heel, noting that the marks are from a different farrier, who probably rasped the heels to help make the shoes fit. It’s not a practice that Downs approves of.

As he shoes the horse, Downs explains that with reiners, palmer support is more important in the slide and stops, while lateral support is more vital when the horse is doing turnarounds or roll backs.

Again, he notes that because the horse will have to do some of each maneuver in every pattern, a farrier needs to keep all the movements in mind.

1:33 p.m. Once he’s finished shoeing the Morgan, Downs packs up his shoeing rig. He checks the feet of a couple of other horses and talks with Garrison about what horses he’ll need to see on his next visit. He writes up his bill, and heads for his next stop.

While driving to the next stop, Downs says his prices are middle of the pack for this area of Colorado. For all the horses he’s seen so far today, he’ll charge from $135 to $165. All the horses were shod all the way round. Adding pads and other charges account for the higher amounts.

He also says he really enjoys working with a client like Garrison.

Downs shares a laugh with a client as he looks over her horse’s feet. The horse is one he needs to keep on a regular schedule. The gelding tends to grow a lot of heel and if he goes too long between shoeings, will develop toe separations.

“Gabe is a real horseman,” he says. “He’s a great trainer and an excellent rider. The health of his horses is very important to him. He takes care of his horses. He’ll use ice, wraps, medication and whatever therapy it takes. He also appreciates what good shoeing and hoof care contribute to good performance.”

Garrison and Downs have developed a good dynamic. They are about the same age and come from similar backgrounds. Both were college baseball players and both are relatively new to their respective trades. They’re both eager to learn as well as to advance their careers.

“I think we relate well to each other because of some of the similarities in our backgrounds,” says Downs. “We communicate well and are both willing to try new ideas and think a little outside the box.”

2:43 p.m. The next stop is at Hearts and Horses, a therapeutic riding center. The first horse Downs works on there is a gelding named Skittles. The horse has a pleasant personality, but it’s safe to say he’s not anywhere near the same class as the horses at GLG Performance Horses.

Skittles has had some laminitic episodes after he was placed in a stall with wood shavings that — unknown to the owners — included some black walnut.

Downs picks up one of Skittle’s feet and points out that there’s no definition to the white line, and that the horse is crooked-legged as well as crooked-footed.

Downs says he generally can reset sliding plates one time. But in this case, Skittles drags his toes so much that the shoes don’t have enough metal left for resetting.

While Skittles still has some issues, Downs say his feet are looking much better than they did during his last two shoeings, so progress is being made.

He’s careful with his trim, noting that “less is more” in a case like this.

3:43 p.m. After Skittles is back in his stall, Downs does a quick trim on Tex, a pony. It’s almost more of a shaping than a trimming, as the pony’s natural movement seems to keep his feet pretty well in shape. Downs hardly touches the sole, but does shape up the hoof wall a bit with his rasp.

3:55 p.m. The last horse at this stop is a big Quarter Horse. The trim goes quickly. Downs does roll the horse’s toes just a little bit. Again, on the sole, he does little more then clean out flaking dead sole.

“He doesn’t have a lot of sole and the ground here is pretty hard, so I’ll hardly touch that,” he says.

4:17 p.m. Downs’s final stop of the day is at a smaller barn, where he takes care of several horses. Today, he’s shoeing an older, retired reiner, who is still used for lessons and trail rides.

The horse has had some thrush and white line problems. When Downs nails on the shoes, he used copper-coated nails from Horseshoes Unlimited. He thinks they have an effect on fungal problems, although he emphasizes that he’s also careful to deal with any balance issues or other problems that might cause wall separations that give organisms a pathway into the foot.

4:49 p.m. Downs wraps up his day by checking the hinds of Shiloh, a gelding. Shiloh has a show in 2 weeks, and Downs tells the owner the horse will need to be reset before then.

Downs keeps an eye on Shiloh and tries to keep him on a strict schedule. The gelding grows a lot of heel, and if he gets off schedule, he can develop hoof wall separations in his toes.

He’s shod the horse three times now, and is still in the process of getting the feet to where he wants them, but he does feel he’s getting close.

The day has been a relatively light one for Downs — in part because of his willingness to accommodate an AFJ editor. He’d ordinarily make at least one more stop. It’s a busy time of year for farriers along the Colorado Front Range.

Downs says quite a few farriers work in the area, including many top hands. While there’s obviously competition among shoers, Downs says there are also a lot of horses. He finds farriers in the area very willing to help each other out and says he’s benefited greatly from the willingness of more experienced farriers to help him develop and polish his skills.

Downs regularly attends hoof-care clinics and contests. Just the weekend before, he won the Division 2 Live Shoeing Championship at the 4-Corners Contest. He regularly participates in two-man draft competitions with his partner, Jacob Manning of Roosevelt, Utah. He finds shoeing competitions to be great learning experiences, not just for the forge work, but for the chance to talk and interact with other farriers.

“Everything I know, someone else taught me,” he says. “I feel very fortunate.”

Downs is fortunate, but his willingness to learn and hard work while Shoeing For A Living means that fortune is earned

Post a comment

Report Abusive Comment