The stifle joint plays an important role in overall health and performance. Often coined the most complex joint in the horse’s anatomy, it is akin to the human knee, serving a myriad of roles including shock absorption, propulsion and weight support.

The stifle joint’s complexity subjects it to a variety of pathologies that range in severity from a decrease in performance to crippling lameness. Understanding this important joint — and how shoeing affects it — can help farriers prevent and treat stifle conditions when they arise.

Understanding the Joint Structure

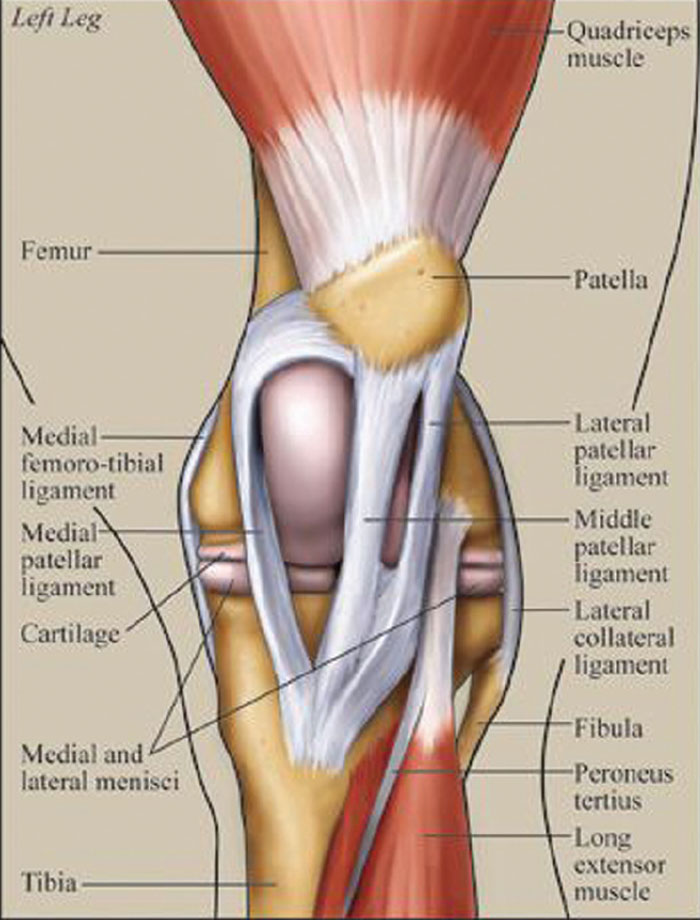

The stifle is comprised of bone, cartilage and soft tissue structures, according to Trent Bliss, DVM, professional services veterinarian at Boehringer Ingelheim. All totaled, three bones, three smaller joints and 14 ligaments work in tandem.

“In the past, we’ve primarily been concerned with the bones and cartilage,” Bliss says. “As we’ve evolved as a veterinary profession and the tools we use for diagnostics have improved, our understanding of anatomy has become more well-rounded. We know more about biomechanics than we ever have, and that’s changing the way we look at the stifle joint.”

The femur, tibia and patella are the three bones found in the stifle joint.

“The femur extends down from the pelvis and rests on top of the tibia,” Bliss explains. “The patella is like a human kneecap, sliding along the femur when the joint flexes. The patella, bottom of the femur and top of the tibia are all covered in cartilage.”

Bliss says three distinctive joint pouches are also found in the stifle — the medial femorotibial joint, femoropatellar joint and lateral femorotibial joint.

“I want to protect the trim with a shoe in stifle cases…”

“The medial femorotibial joint is the biggest joint pouch and it’s located on the inside or medial aspect of the stifle,” Bliss says. “The middle pouch is known as the femoropatellar joint and is associated with the patella. The third and final joint pouch is the lateral femorotibial joint and is located on the outside or lateral aspect of the stifle.”

Two menisci, known as the medial meniscus and lateral meniscus, are cartilage pads that help absorb shock within the joint. Lastly, 14 ligaments including the medial and cranial cruciate ligaments, caudal and cranial cruciate ligaments, femoral patellar ligaments and meniscal ligaments work with the patellar tendon to ensure stability within the stifle joint.

Common Ailments

Because of its complexity and workload, the stifle joint is a common source of problems in both recreational and performance horses. Although it can be affected by single-event traumas like a kick, fencing mishap, or rotational injury, Bliss says most stifle conditions are the result of repetitive stresses absorbed by the joint over time.

“What we see most commonly in the stifle joint are injuries caused by wear and tear,” he says. “The best analogy I can use to explain it is this: you have two 1-ton dually trucks. They’re the same, except one truck has 36,000 miles on it and the other has 136,000 miles. You expect to see more problems in the one that’s gone down the road more and that’s true in all the joints and soft tissue structures of the horse.”

Shane Westman, the University of California, Davis, farrier agrees, noting that most wear-and-tear injuries occur in performance horses that rely heavily on their hindquarters — including many Western performance horses, working cow horses, reining horses and jumpers.

Takeaways

- Although there can be genetic and conformational influences, most stifle injuries are caused by repetitive stresses on the joint over time.

- Signs of pain can range from subtle changes in gait and limb asymmetry to outright lameness, depending on the degree of severity.

- A 4- to 5-week hoof-care schedule is important to care for stifle injuries to keep the lever forces in check. These forces tend to add to wear and tear.

“In my experience, these injuries aren’t isolated to any one discipline,” Westman says. “There can be genetic or conformational influences, but the majority of the stifle pain we see at the hospital is the result of stress endured by the joint through the course of a horse’s performance career.”

In most cases, stifle pain caused by repetitive stresses can be successfully managed with regenerative joint care therapies or steroid joint injections, coupled with a period of rest for the horse.

In addition to repetitive traumas, Bliss says certain breeds of horses are prone to osteochondrosis dissecans (OCDs) of the stifle. OCDs are considered an orthopedic disease and occur most commonly in the hocks, stifles and fetlocks of growing horses.

“OCDs are fairly common in Quarter Horses and warmbloods,” he says. “In some cases, an OCD is in an area that doesn’t communicate with a joint directly and can be pretty benign. On the other hand, some OCDs cause significant lameness and may require surgery for the horse to be sound for riding or performance — it’s a matter of location and severity on a case-by-case basis.”

Although rare outside of miniature horses, Bliss says upward fixation of the patella is another condition that occasionally causes problems in riding horses. This occurs when the medial patellar ligament hooks over the trochlear ridge of the femur, locking the limb in extension.

The Equine Stifle Joint

“Upward fixation is a neat thing every horse can do,” he explains. “They can lift their patella and set it on the medial trochlear ridge of the femur. It locks the leg in a fixed position so it can rest while standing without any muscular effort.”

When a horse is unable to control the locking and unlocking of the patella over the medial trochlear ridge, it can cause limb asymmetry or lameness in varying degrees. Upright stifle conformation and poor rear hoof angles can contribute to upward fixation of the patella, but Bliss says the most common culprit is poor fitness.

“Proper conditioning develops the muscles that support the stifle joint,” Bliss says. “When they’re experiencing that fixation it’s because they lack the quadricep strength to pick the patella up and return it to its normal position. The increased muscle tone developed through exercise allows the horse to remove the patella from the trochlear ridge. This is one of those situations that is easy to manage because the prescription is usually just more exercise — stall rest and immobility do more harm than good.”

Tell-Tale Signs of Pain

Signs of stifle pain may range from subtle changes in gait and limb asymmetry to outright lameness depending upon the degree of severity.

“Symmetry is a big indicator for me, so I always start there,” Bliss says. “Is the horse symmetrical from side to side? Is there equal muscle mass? Is there any obvious joint effusion? These are things a farrier and owner can be aware of.”

Toe wear is another way farriers and owners can monitor stifle health.

“It’s not fail proof because there are horses that are just lazy and drag a toe,” he cautions. “But anytime there is a new wear pattern in the toe, squared toes, or a lot of unnatural wearing at the toe, it’s worth investigating — these can all point toward a potential stifle issue.”

Learn More Online:

Gain more insight about the stifle by reading:

- “The Critical Importance of the Horse’s Stifle and Hock in Movement,” in which Dr. Deb Bennett details how the hind limb reciprocating system coordinates motion and economizes the required effort.

- “Horse’s Stifle Anatomy Integral for Rest and Snoozing While Standing,” in which Bennett details how the hoop-and-lock system allows equids to lock and unlock the hind legs.

Westman agrees and encourages farriers to be observant of these and other potential tell-tale signs of stifle pain during routine farrier visits.

“Farriers are in a unique position to see small issues before they develop into big problems,” he explains. “When we trim or shoe a horse, we are putting the leg in a similar position to what the vet uses when flexing a horse’s stifle during a lameness exam — and we’re asking the horse to hold that position for a prolonged period. So, we’re often the first to experience discomfort in the stifle.”

A horse that resists holding its leg in this position or tries to draw the leg back after it’s been picked up may be experiencing stifle pain.

“I’ll think of the stifle right away, especially if the horse has generally been good to work on and suddenly starts resisting,” Westman says. “I have the luxury of working in a veterinary hospital where I always have access to a vet, but if I didn’t, this would be where I would recommend the owner have their horse evaluated. As farriers, we are on the front lines — and that puts us in a unique position to catch problems while they’re still small.”

Shoeing the Stifle

While Westman says there isn’t a one-size-fits-all formula for shoeing for stifle health, there are certain techniques he’s successfully implemented over the years.

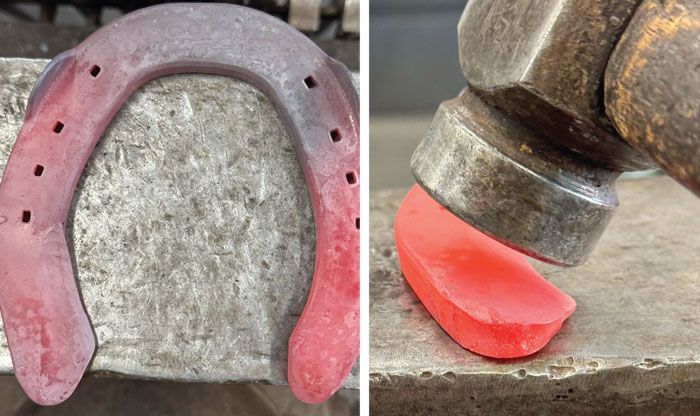

“A lot of what I see in the hospital is medial patellar ligament issues,” he says. “These horses like to come off the inside of their toe, so you want to roll the toe — not straight in with the foot, but from the mid-toe over to the mid-quarter, or from the middle of the toe around to the second nail hole.

“If I’m trimming, I can trim it in, but without the shoe, it’s unprotected and will wear itself incorrectly,” Westman continues. “For that reason, I want to protect the trim with a shoe in these cases. Normally, the goal is bony column alignment, but this is one of those situations where I’ll fudge it to help the horse out a little by leaving the lateral heel high and tipping it toward the inside.”

In severe stifle cases, Shane Westman widens the lateral heel and rolls the medial toe. The University of California, Davis, farrier will also sometimes swell it so it’s taller. “I usually use widths and try to manipulate the foot that way — it seems to be less impactful on the foot than wedging one side.” Photo by: Shane Westman

In more severe cases, Westman advises widening the lateral heel of the shoe in addition to rolling the medial toe.

“If I have to, I’ll even swell it so it’s a little bit taller,” he explains. “I usually use the width of the shoe web and try to manipulate the foot that way — it seems to be less impactful on the foot than wedging one side.”

Bliss cautions farriers should also be aware of how traction affects stifle health.

“The traction on your shoeing package should always consider the type of work the horse is doing,” he advises. “A buggy horse traveling on the pavement needs more traction than a reining horse. If we put that much grip on a reiner, we would see a tremendous amount of stifle injuries. So, we put sliders on a reining horse and rasp the nail heads flat and sometimes add trailers. These help combat the torsional stress that the horse undergoes.”

Maintaining a routine farrier schedule will prevent and catch stifle issues early.

“In my general practice, I see horses at a maximum of 6 weeks,” Westman says. “If a horse has a known stifle issue, a tight schedule becomes more important. I see a lot of horses in the hospital every 4 to 5 weeks because it allows me to keep in check the lever forces that tend to add to wear and tear. Good management is key in these cases.”

Communication is Key

Achieving optimal results in horses with stifle issues requires cooperative care between the horse’s veterinarian and the farrier. While Bliss acknowledges communication can present unique challenges on both ends, he says it’s important that vets and farriers collaborate on behalf of the horse.

“There needs to be good two-way communication in place,” he says. “I need to be able to communicate to the farrier what I think needs to happen and then I need to have enough respect for that professional to let them do their job.”

Photo by: Shane Westman

Bliss refrains from making suggestions about how to best shoe a horse. Instead, he educates the farrier about the horse’s problem and the end goal, then allows the farrier to determine the shoeing.

“Lameness medicine is part science and part art and the same is true of farrier work,” Bliss says. “Good farriers are artists and it’s amazing what they can do when they combine that talent with a good understanding of science and biomechanics.”

Westman agrees that a good working relationship between the veterinarian and farrier is an integral part of the horse’s management.

“The dynamic between the vet and farrier is so important because communication influences the success of the shoeing prescription,” he explains. “In a best-case scenario, the vet makes a diagnosis, discusses the goals with the farrier and then allows the farrier to come up with an individualized plan.”

A good relationship with the veterinarian also allows for troubleshooting problems when necessary.

“Farriers tend to like working alone,” Westman admits. “We don’t always like to collaborate, but there’s a definite benefit to developing a team of professionals who respect each other, work well together and can tackle problems when they arise.”

Managing Client Expectations

The need for good communication extends beyond the veterinarian-farrier relationship, Westman says.

“It’s easy to overlook the importance of communicating with clients, so we have to be vigilant about that,” he says. “Open communication between the farrier and the client sets the stage for a good working relationship with the free exchange of information going both ways.”

Good communication also allows farriers to manage client expectations realistically.

“I’m never overly confident with the owner about my shoeing package,” Westman explains. “I always want to leave the door open for it not to work and I want the client to feel like that’s a conversation I’ll welcome. I don’t ever want the client to feel like they can’t come back to me with a problem.”

Because shoeing to manage stifle issues doesn’t work on a one-size-fits-all basis, Westman says it’s important that clients understand that it may take more than one try to find the shoeing package that best fits the individual horse.

“Horses don’t read the books, so it’s vital the farrier and owner don’t get hung up on one approach,” he says. “We have to be willing to listen to the horse and make adjustments, so I always have a plan for the next step — and that’s something I make sure the client knows. If plan ‘A’ doesn’t work, I have two or three more ideas already in mind.”

Post a comment

Report Abusive Comment