Heel pain is a common problem in performance horses. While treating it often requires trial and error, ingenuity and a good foundational trim lead to a positive prognosis for many horses.

Once associated almost exclusively with navicular syndrome, heel pain is now known to originate from a variety of conditions, including dysfunction within the navicular apparatus, underlying inflammation in the internal hoof structures and poor hoof balance.

Blane Chapman, an American Farrier’s Association (AFA) Certified Journeyman Farrier of Vernon, Texas, works with horses competing in a variety of Western disciplines. Through his practical approach to managing horses with heel pain, many of his clients’ horses have been able to return to successful competitive careers.

An Ounce of Prevention

While some horses can be predisposed to navicular syndrome or unspecified heel pain, Chapman says these diagnoses tend to be problems that are secondary to a shared common denominator: a poorly balanced hoof.

Farrier Takeaways

- Heel pain in performance horses tends to be problems that are secondary to a poorly balanced hoof.

- Executing a balanced trim begins with the ability to recognize external hoof distortions and understand how best to restore the hoof to more ideal parameters.

- The correct horseshoe often plays a role in optimizing outcomes.

“When somebody says their horse is heel sore, navicular is usually the first thing we think about,” Chapman told attendees at the 2023 International Hoof-Care Summit in Cincinnati, Ohio. “But with most of the horses that come to me, that’s not the primary problem — it’s generally a secondary response.”

While Chapman says some horses have a confirmed problem in the navicular apparatus, most have incurred months, or even years, of trauma to the internal hoof structures because of a poorly balanced trim.

“Preventing these problems starts with the trim — every bit of it,” he says. “In our work, we deal with normal feet, upright feet, club feet, feet that are broken forward and feet that are broken back.

“What we get into trouble with most of the time in horses with heel pain is feet that are broken back,” he continues. “Horses’ feet grow down, but they also migrate forward — this can leave the broken-back axis we refer to as no or low heel (Figure 1). When we address a horse with heel pain, we have to be able to visualize a normal foot inside all of the mess and take the foot back as close to its normal angle as possible to alleviate stress on the internal hoof structures.”

A low heel with a broken back axis is a common source of heel pain.

Bank on a Balanced Trim

Executing a balanced trim begins with the ability to recognize external hoof distortions and understand how best to restore the hoof to more ideal parameters, Chapman says.

“I begin with identifying the apex of the frog (Figure 2),” he explains. “If you look at most mapping protocols, such as those suggested by William Russell or Mark Caldwell, they are more or less the same. The exception is a study by Cody Ovnicek, which is based on theories by Gene Ovnicek and David Duckett using radiographic imaging that the widest portion of the foot is 1 inch back vs. ¾ of an inch back.”

A balanced trim begins with locating the apex of the frog.

If you can’t find the true apex of the frog, Chapman advises locating where the bars terminate into the sole.

“Where the bars terminate into the sole should be the widest part of the foot,” he says. “That will be an inch back from the true apex of the frog. If you go an inch forward from that, it will be a good indication of where the true apex of the frog is.

“You can also run your hoof knife or hoof pick in the commissures — there will be a ridge there,” Chapman continues. “A lot of horses have a hump right there, too. If you follow that to the peak of the ridge, known as Duckett’s bridge, you can find the widest part of the foot, draw a mark across there, and go forward an inch from that to find the true apex of the frog.”

“Preventing heel problems start with the trim…”

These visual markers also indicate the point where theoretical breakover occurs.

“According to Ovnicek, Duckett and Caldwell, 1¾ inches forward from the widest point of the foot is approximately where the distal end of P3 is located — ¼ of an inch forward from that is where you should find theoretical breakover,” he explains.

Chapman recommends putting these principles into practice to refine skills.

“Get a marker and draw on their feet,” Chapman advises. “Ask questions like, ‘Where is the frog? Where is the widest point of the hoof? Where does it measure from the apex of the frog? Where does it measure from the widest point of the foot?’ They’re not the end-all, but they’re a very good guide, and they will give you a lot of information about how much distortion the horse has at the toe.”

Shoeing for Success

Preventing heel pain may begin with a balanced trim, but Chapman says the right horseshoe often plays a role in optimizing outcomes.

“I have quite a few different shoeing packages I’ll use, depending upon the needs of the horse,” he says. “I shoe a lot of high-speed performance horses, so I often have to balance the therapeutic needs against what the horse needs to perform.

“We live in a convenience store world and most horses aren’t going to get 6 months to swim while they get well,” Chapman continues. “Clients want their horses going down the road right now. When a horse comes to me, I have to figure out what is best for today. I need a shoeing package that is going to let the horse perform to the best of its ability during the process of me trying to get its feet right therapeutically.”

While Chapman says each horse requires an individualized approach, he often relies on heart bar shoes (Figure 3), spider plates (Figures 4a and 4b) and wedge shoes with or without a wedge pad.

A heart-bar shoe is a good option for many horses experiencing pain in the navicular apparatus or unspecified heel pain.

A spider plate provides extra support without adding too much extra bulk on the ground surface, making it a viable option for horses that compete in high-speed events.

“I like the spider plate and heart bar shoes because you don’t have a bunch of extra material on the ground,” Chapman explains. “You have support up against the foot surface and frog where the horse needs it and the foot can still function, so you get the support and stability you need without the extra bulk on the ground surface.”

In addition to choosing the correct shoeing package, Chapman emphasizes the importance of proper shoe placement.

LEARN MORE …

• Reading, “Handling Footcare at the 6666 Ranch.”

• Reading, “Training the Next Generation of West Texas Farriers.”

• Watching, “Mapping the Equine Hoof.”

“There’s a fine line between leverage and support with a shoe,” he cautions. “Going past the heel bulbs can add leverage, primarily in the landing phase of the stride. In horses with compromised caudal structures that are competing in high-speed events, I find a compromise between utilizing a hunter fit and a leisure fit from AFA certification standards often yield the best results.”

Lastly, Chapman encourages farriers to consider the effect that the weight of a chosen shoeing setup may have on a horse.

“I often hear people say, ‘It doesn’t matter because the horse weighs 1,200 pounds,” he says. “But in horses that are performing, it’s important to match the thickness and width of the shoe stock to the horse’s job. It’s especially important in high-speed horses where events are coming down to hundredths of a second, weight plays a big role in deciding what package I’m going to use on that horse.”

Case Study: An Ounce of Prevention

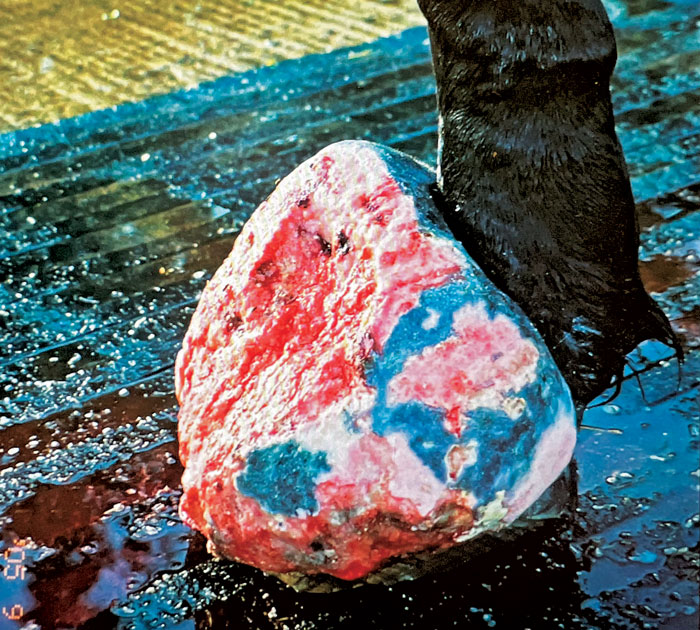

Anytime a foreign object is introduced into a joint space, infection is a risk. Here, an infection in the coffin joint developed post-coffin joint injection, resulting in 14 pounds of granulation tissue.

“Mandy” presented with 14 pounds of granulation tissue as the result of a coffin joint infection obtained post-coffin joint injection. A high-end harness racing horse, Mandy’s owner’s original complaint was heel pain causing lameness and performance problems.

“He kept coming up sore, but they just kept shoeing him the same way,” explains Vernon, Texas, farrier Blane Chapman. “They had his foot strung out in front of him. He is a Standardbred and didn’t have the best feet to begin with, but they didn’t change anything about the way they were taking care of his feet.”

When shoeing didn’t alleviate Mandy’s symptoms, his coffin joints were injected. He improved in the short term, but quickly regressed. After coffin joint injections proved fruitless, his navicular bursae were injected. Again, this relieved his pain temporarily, but the lameness quickly returned.

“They continued injecting his coffin joints and navicular bursae, and he continued to be lame,” Chapman says. “All the while, he kept breaking down because the mechanics were still in play.”

Chapman says Mandy’s case is a prime example of the importance of a balanced hoof.

“Most of the horses that come to me with navicular syndrome or heel pain are experiencing these problems as secondary issues,” Chapman explains. “With Mandy, the heel pain was not the primary issue. This was a mechanical situation early on and preventative maintenance would have quite possibly gotten Mandy a lot further down the road than injections.”

By the time Mandy arrived under Chapman’s care, managing the ongoing heel pain took a backseat to the more pressing issue: 14 pounds of granulation tissue needed to be removed.

Chapman enlisted the help of a veterinarian who was able to successfully remove the mass and work to correct the poor hoof mechanics began. Even though this case boasts a positive outcome, Chapman says Mandy’s story should serve as a cautionary tale for others who are treating heel pain.

“This horse ended up with a secondary infection from an injection site,” Chapman says. “Anytime you start introducing invasive procedures, whether you’re a veterinarian or a farrier, you’re susceptible to trouble. As a result of all this, the granulation tissue was also secondary. Everything stemmed from trying to help the horse with heel pain and this is where we ended up. The injections gave relief, but the mechanics were not addressed. The suspensory apparatus failed and the coffin joint became infected, hence the abscesses leading to granulation tissue. This is a worst-case scenario.

“This horse needed prevention and that comes from trimming balanced feet,” Chapman continues. “It’s a matter of getting the horse’s feet in the proper place where we don’t have these problems. Most of the horses that come to me, unless they have a heel bulb avulsion or an injury, have heel pain that is secondary to poor hoof mechanics. Prevention is key.”

Seeing the Big Picture

Hoof care on a routine schedule is of paramount importance for horses with heel pain. And while it’s not possible for every client, Chapman makes sure to educate each of them about the benefits of consistent farrier care.

“I tell my clients, ‘Hey, this is what we need to do for an ideal outcome. This is what it’s going to cost, and this is what’s going to happen if we do this,’” he says. “If a client doesn’t have the horse done regularly, I can’t control that. Every time I shoe the horse, I strive to see a normal foot inside the one that’s distorted. I try to put the horse’s foot in the best possible position that day because the reality is there’s no guarantee when I’m going to see that horse again.”

Chapman also advises to look at the immediate needs of the horse against the backdrop of the bigger picture.

“My goal is to get the hoof as close to normal as possible without manipulating it to the point where it adversely affects the horse down the road,” he explains. “I have to figure out what I can do best for him today, but not just shoe him for today. I don’t want to shoe him for 6 weeks or even 6 months from today — I want to shoe him for 6 years from today.”

Post a comment

Report Abusive Comment