American Farriers Journal

American Farriers Journal is the “hands-on” magazine for professional farriers, equine veterinarians and horse care product and service buyers.

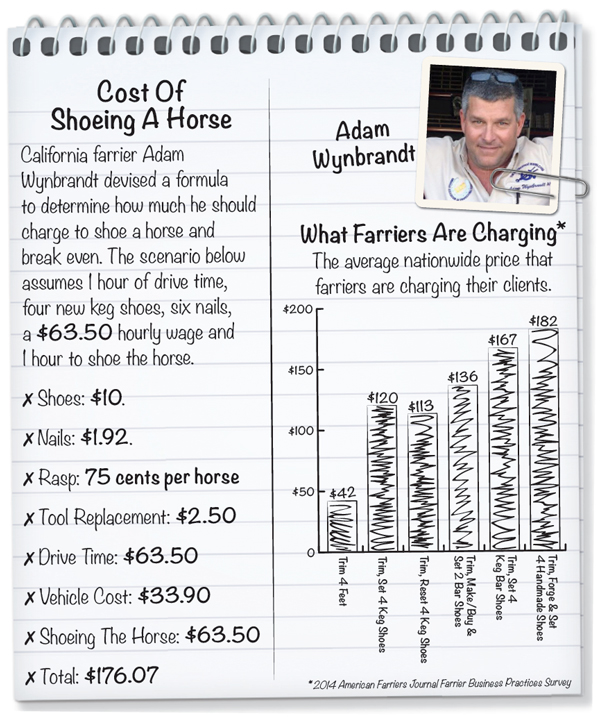

What can you charge?

It’s a question that farriers commonly ask and one that Adam Wynbrandt hears often. His response?

“I tell them, ‘Well, no, the question is, what do you need to charge?’” says Wynbrandt, who has 2 decades of farriery experience and owns The Horseshoe Barn in Sacramento, Calif.

Even veteran farriers struggle with finding a winning formula, but Wynbrandt finds there’s a common mistake.

“Most farriers work off of gross income rather than net,” says the American Association of Professional Farriers board member. “What’s the difference? If you just did six horses for $600, that’s your gross income. That’s all your money. In reality, you have costs, expenses and taxes. The amount of money you have after those expenditures is your net income.”

According to the latest Farrier Business Practices survey conducted by American Farriers Journal, the average nationwide price for trimming four hooves and applying four keg shoes is $120.19. The average charge for trimming and resetting four keg shoes is $113.36. Trim-only prices average $42.06.

|

Those prices might not work for you and your situation, though. Wynbrandt, for instance, shoes horses in California, which has a higher cost of living than most states. Then again, the prices might indeed fit your lifestyle, you just need to budget your income more efficiently. That’s where Wynbrandt found himself just 2 years into his career. Wynbrandt’s practice was thriving, but he was in for a rude awakening.

“I went in to get my taxes done,”…