While shoeing any type of performance horse, we always consider toe grabs carefully.

Toe grab discussions always involves a conversation about the height of those toe grabs, but there is more to the influence of toe grabs than just how high it sticks up from the shoe. There is also the consideration of leverage from hoof growth and the orientation of a shoe on the hoof. Both can have a significant affect on how the grab serves or hinders the horse. When it’s too far forward, it can have one effect. When it’s too far back, it can have an entirely different effect on gait and/or soundness. The duration of shoeing interval and amount of hoof growth can also change the way a shoe and toe grab affect the lower limb.

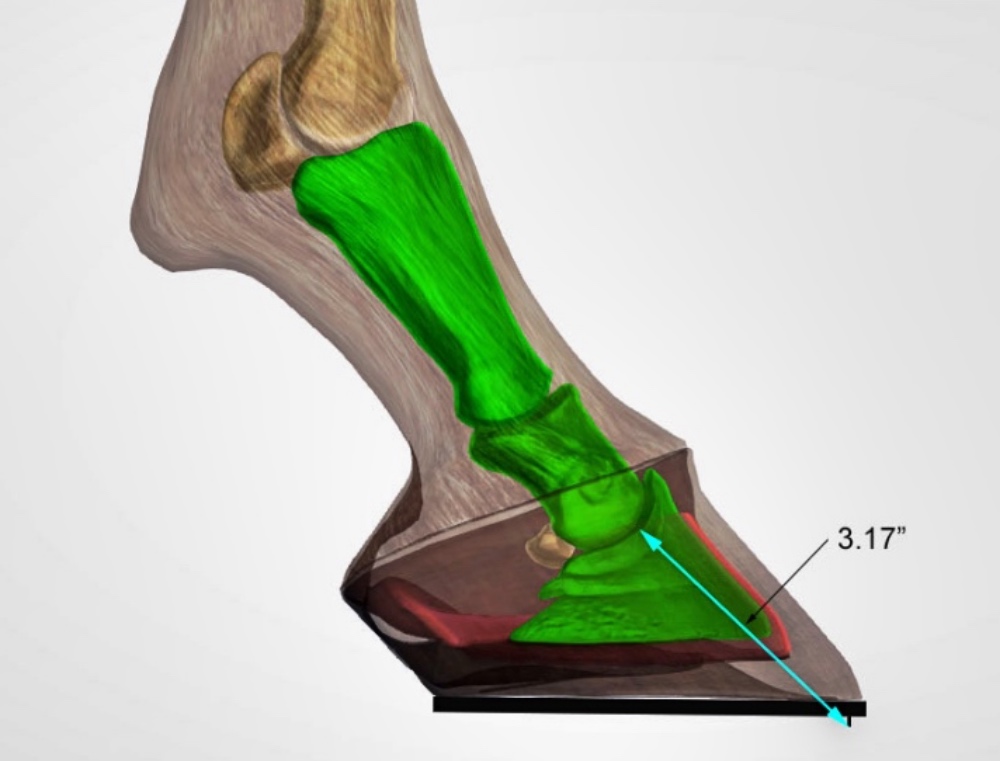

Figure 1 shows a hoof that is freshly shod. The three pastern bones — long pastern, short pastern, coffin bone — are in good alignment in this illustration. The only change to this orientation would be hoof growth and shoe placement. The bones are no longer growing in a mature horse and the coffin bone will not change position within a healthy hoof capsule. The location of shoe placement relative to the coffin joint can have a huge effect on gait dynamics and soundness. Assuming this is true, so too can hoof growth change the shoe/grab dynamic.

When a shod hoof grows it is not the same as barefoot hoof growth. The horseshoe affects hoof growth in two ways.

First, the toe of many horseshoes will create resistance against the natural breakover of the hoof during each stride. This resistance can lead to dorsal (front) hoof wall distortion. This will always be forward distortion. As the shod hoof grows, it tends to grow/distort forward more than a bare hoof would. Dorsal hoof wall migration should be managed by the farrier at every shoeing interval. The second affect from a shoe is that it will eliminate the natural erosion of hoof wall, primarily in the toe area.

Figure 2 shows a hoof shod with toe grab after hoof growth, and yet within the normal shoeing cycle. Notice the changes in distance from the center of rotation at the coffin joint to the toe grab. The toe grab effect does not remain constant throughout a shoeing interval. This happens to every hoof in varying degrees, depending on shoe placement and growth rate of the hoof. It should be taken into consideration when deciding on toe grabs. And will probably merit consideration for “target” races.

Given the mechanical advantage of levers, this is at least as important as toe grab height. It also bears significance to the argument as to whether toe grabs should be as much in younger horses. Agree or not about toe grab use, it’s important to say that any influence from toe grabs is not a static effect that stays the same day 1 to day 30.

We have all seen the horse that is hitting after the toes get long. Hoof growth alone is not the only explanation. The “how” is grab height, the “when” is shoeing duration, and the “where” is relative location to the coffin joint, which is not a constant.

The next time we ask ourselves how, when, and where did this horse start hitting itself, it might be time to re-evaluate toe grabs as well as the hoof growth. To grab, or not to grab, time will tell.

Post a comment

Report Abusive Comment