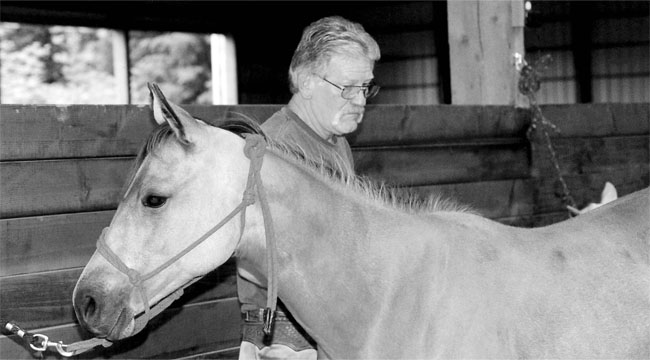

STILL SHOEING. Even though he’s had two hip-replacement surgeries, Russell Stout of Reedsport, Ore., has no range of motion limitations or restrictions. Everything he did before, he can do now, but without the pain.

When Russell Stout went to Oregon State University’s farrier school in 1999, he was no spring chicken. He had just finished 32 years of employment with International Paper Co. and had two daughters who were in their mid-30s. At school, students in their late teens surrounded him. But that didn’t dissuade him. Right away he knew he’d found a profession he would love. “I could kick myself for not doing this when I was a young man,” he says.

After taking both the basic and advanced farrier classes, he was a certified journeyman and jumped right into establishing his new business. Soon, he had clients he liked and plenty of horses to work on. It just couldn’t get any better.

Until the pain started, that is.

He recalls he didn’t want to seem like a whiner as he grewolder. But at night, his hip joints throbbed with so much pain that he couldn’t get much sleep. “I tried to sleep with a pillow between my legs,” he remembers. “But whenever I turned over, the pain would wake me up.”

During the day, it didn’t seem to affect his mobility, unless he worked on a horse that jerked him around. But there was still an element of danger because of his failing joints.

“If I were to walk and stumble, I would probably have fallen, because I couldn’t get my hips to work right,” he recalls.

Bad News

By fall of 2000, Stout knew it was time to face up to the pain and see a doctor. He was referred to an orthopedist who dropped the bomb and told him he needed hip-replacement surgery.

Stout’s first reaction was the same as it would be for most farriers. “There goes my job.” But the more he talked to the doctor, the easier it was for him to make the decision to go ahead with the surgery.

The doctor told him that he could keep doing what he had been doing, after the recovery period. Stout became very positive about the possible outcome.

“My whole attitude was that the reason I was going to have this done was because I was in pain and didn’t want to be laid up,” he says. “I wanted to continue the same kind of lifestyle that I was accustomed to. I’m not a couch potato.”

For most of his adult life, Stout had used packhorses to hunt big game. He had also spent years calf roping and team roping. Fit and active, he wasn’t the type to give up that kind of lifestyle – or his job as a farrier – because of constant pain.

One At A Time

Stout had one hip joint that was worse than the other and causing the most pain. It was bone-on-bone. The doctor suggested that joint be replaced first because doing so would mean an easier recovery than doing both at the same time. The other hip could wait a while. So, in November 2000, Stout went ahead with that first surgery. He chose this time because it was basically off-season. Business was fairly slow and it would be just 8 weeks before he could be under a horse again.

He did have some regular clients who needed their horses worked on during that time. Bobby Bewley, son of Oregon State University farrier instructor Larry Bewley, came to Stout’s aid. “He took care of my clients while I was laid up,” Stout says. “It worked out fine. I didn’t lose any clients at all.”

TAKE IT EASY. Russell Stout takes plenty of time when working with horses. Here, he stands calmly by a yearling filly and strokes her neck.

Before the surgery, Stout made a commitment to his clients. “I told them I was going to have the operation and said, ‘Don’t worry – I’ll have someone who is qualified and certified take care of your horses while I’m laid up.’”

Stout was able to travel with Bewley when he worked on the horses. “I had some clients who liked things done a little different,” Stout says. He told Bewley their preferences. Not only was it successful, but Stout’s clients said that if he was ever laid up again, it would be nice if Bewley could fill in again.

And, Stout was laid up again, in December of the following year, when he had the other hip replaced. But this time, he says, “I was only in the hospital for 2 days. Four weeks later I was under a horse.”

Don’t Put It Off

Stout says he knows a couple of men who should have the surgery done but are afraid they won’t be able to work like they did before.

“They’re hurting. They’re wearing braces. They just try to deal with the pain,” he says. “But my advice is, don’t do that. Get the surgery, because you’ll feel so much better. With modern technology, you’ll be back to work quickly.”

It’s common to find people who dread having this type of surgery, for fear of long lay ups and the pain associated with recovery. Recent years, though, have seen tremendous advances in this type of surgery. Even since Stout had his last surgery in 2002, there have been more advances in techniques that provide an even less invasive procedure and a faster recovery time. The pain associated with the procedure is also even further reduced.

Years ago, doctors made a 12-inch incision for hip replacements. This called for muscle to be removed from the bone, which not only caused more pain, but also required longer recovery times. Recent technology, however, is changing the way hip replacements are done.

Technological Advances

Dr. B. Sonny Bal, an orthopedic surgeon at University of Missouri-Columbia Health Care Center in Columbia, Mo., performed the first image-guided, minimally invasive hip replacement surgery (MIS) earlier this year. This procedure calls for two small incisions, rather than one large one, to implant the artificial hip components. Radiographic markers are used on the bone surrounding the diseased hip. Fluoroscopic image guidance locates the areas in need of repair. None of the underlying muscles or tendons are cut during this new procedure. This leads to faster recovery with less pain.

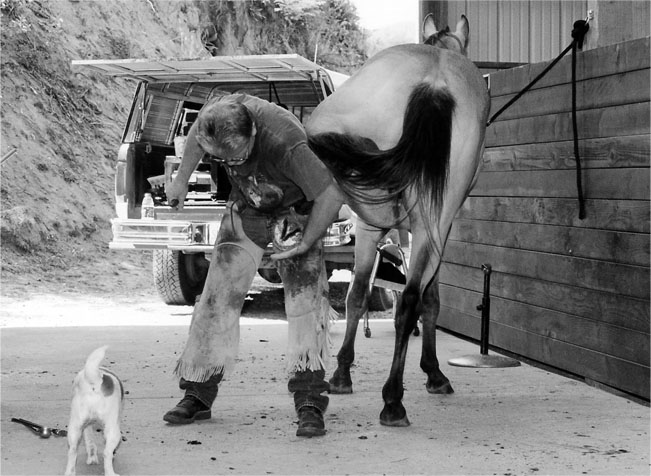

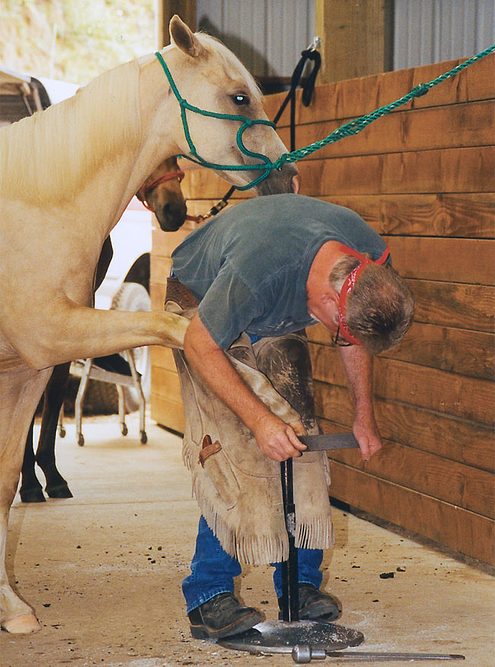

IN CONTROL. Even if a horse resists, Russell Stout has no physical problems handling it. And, with the way he handles horses, the resistance is usually short-lived.

Bal intends to incorporate a similar navigational-guided technique in order to do total knee replacement surgery. This spares invasion of the quadriceps muscle and not only quickens recovery time, but also improves range of motion after the surgery. Bal’s Web site Hip and Knee , has information about the “2-incision MIS hip replacement” and on knee replacement surgery.

Other Reasons To Have Surgery

Patients who put off the surgery not only have to endure continuing pain, they could also be causing further damage to the joints, says Dr. Andrew Shinar, assistant professor of orthopedics and rehabilitation at the Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn.

“When a patient is weighing the pain from arthritis and surgery against having hip replacement, they are doing more harm to the joint,” he says. “Patients are suffering for years when they can have something done to alleviate the problems.”

Stout will be the first to tell you how wonderful it is to be pain free. And, his mind is now calm. Right after the first surgery, however, he was a little worried and cautious. The doctor told him that sometimes, the replacements will “pop out.” Stout thought, “Holy criminy! Pop out?”

But then he realized this happens mostly in elderly people who don’t have the muscle tone to keep the new joints in place. Even though Stout isn’t 30 years old anymore, he says, “I have fairly good muscle tone and shouldn’t be afraid of this.” He says that keeping fit should be on the mind of all farriers, to prevent a number of problems, including back pain.

The surgeon who treated Stout was excited about doing this procedure on a person of his age to see how long the replacements would last. Stout is sort of an “in-betweener.” He was 53 when the first surgery was performed, meaning while he wasn’t exactly young, he didn’t have one foot in the assisted living door, either. Most of the time, these procedures are done on patients quite a bit older than Stout. In the past, replacements lasted only about 10 years before wearing out. But, with new technology, the longevity of the replacements is expected to improve. Some of the components that were originally made of plastic are now being made of ceramic material.

Back On The Job

When Stout went back to work after his first surgery, he vowed he wouldn’t work on tough horses. But gradually, that promise went to the back of his mind. He’s now capably handling anything that comes his way. In fact, he says, “I do a lot of horses now that nobody else will do.”

Because he spent nearly three decades as a horse owner before he became a farrier, he’s got a lot of horse sense. That helps him a great deal with his job. When a horse does react adversely, he figures out the problem, and the resistance is usually short-lived.

“If a horse has been done before with no problem, then acts adversely, there’s a reason for it. He might be sore some place, or have arthritis. Or, he might have been handled rough before,” Stout explains. Not allowing himself to become rushed is one way he keeps things workable, even if a horse is disagreeable at first.

Not Overdoing It

Stout feels that many farriers wear out their bodies with equine wrestling matches and over scheduling. He cautions young farriers against this. Since he’s had his surgery, he reflects often on how he wants to lead a long, active life. He knows if he “pounds his body in the ground” day after day, that’s going to affect his quality of life and shorten the time that he can be productive.

“A lot of the young farriers are driven by big incomes and want to go out and do 15 or more horses a day. Sure, you can make a lot of money that way. But my theory is there’s no reason to work like that,” he says. “If you do, the last five horses at the end of the day are going to look really bad, because you’re tired and worn out. Not only that, but it has a negative affect on the horses you’re doing, because you’re tired and cranky.”

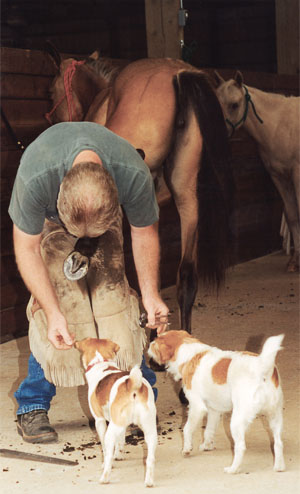

TREAT TIME. Russell Stout takes time to give trimmings to a pair of Jack Russell terriers at Valley View Quarter Horses in Florence, Ore.

The horse senses that the farrier is not comfortable and “It becomes a big wrestling match,” according to Stout. The problems just continue to build. A client who has one of those last five horses is likely to become dissatisfied and can’t understand what’s happening. He or she will wonder, when the farrier did such a good job on this horse before (probably at an earlier time in the day), why the job is so bad this time.

“The client doesn’t put two and two together,” Stout says.

Stout believes in allowing plenty of time to work on the horses he schedules. “I had a theory in my mind that I wanted to do about six horses a day, and only go 5 days a week.” While he’s backed off from that somewhat, he still tries to stay close. This not only gives him some free time, but also saves him from wearing out his body. It also gives him plenty of time to work on each horse, without stressing because he’s due at another barn in a few minutes. That calm attitude helps horses respond in a quieter manner to him.

“Because I’m a little older, I’m also a little slower,” he tells his customers. They know that he’s fussy – a perfectionist who wants to take the time to be sure each foot is balanced. “Most of my clients really appreciate that,” he says. “If a horse has a problem, I can take the time to work on it, and it doesn’t mess up my schedule for the rest of the day.”

Watching Out For Snowballs

He says that farriers who rush and overbook are often hit by stress from the snowball effect. Say that a horse being done in the morning takes longer than anticipated to shoe. “It makes you late for your next appointment,” he says. “Then it kind of mushrooms on you throughout the rest of the day.”

Still The Same Man

Strout hasn't had to change his stance or the way he works, since his surgeries. Another positive is that he is now very aware of how to use his body and time in a way that will allow him many more productive years to trim and shoe a horse. And the best part? He's pain free. He urges other farriers who need this type of surgery to strongly consider it.

Post a comment

Report Abusive Comment