What would be your first reaction if I were to tell you that during laminitis the coffin bone cannot, does not, and will not rotate? Ever!

Not being one to shy away from an argument, I’m going to start off by throwing some gasoline on the fire. Namely, bones never rotate. Why should the coffin bone be so special? Can the cannon bone rotate? The skull is a bone. Can it rotate? Bones articulate at their joints during movement, but never at any other time.

With a laminitic horse there cannot be — nor is there — rotation of the coffin bone. We have always been taught that the coffin bone in a laminitic horse rotates downward, and our concept of shoeing the laminitic horse is based on that idea: to support the bony column in an attempt to stabilize the so-called rotation.

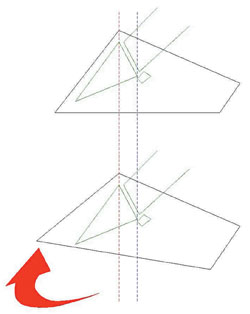

Bones don’t rotate, but the hoof capsule can be displaced and thereafter distort (Figure 1). Mike Wildenstein, FWCF hons, CJF, the resident farrier at Cornell University’s School of Veterinary Medicine, first introduced me to this concept of upward displacement of the hoof capsule. At that time, I could not or would not allow my mind to fully grasp the concept. It went against everything I had ever been taught or read. I did extensive research and found little or no information to support this theory. Since I love to think outside the box, I began to reason it out logically. Interestingly, it took a very painful experience to make it all click.

Ah-Ha! (And Ouch!)

My “Ah-ha” moment came when I whacked my thumb while driving the last nail into a heart bar shoe for a laminitic warmblood. The horse zigged, I zagged, and my thumb suffered. After finishing the hoof, I teetered out to my truck and after I had my wits about me again (following a trip to the drill press to drain the blood that was rapidly gathering under my thumbnail), it occurred to me that I had induced a case of laminitis (albeit mechanically).

The trauma to my finger had created inflammation in my laminae. The extent of the damage eventually caused the nail to begin sloughing off (which it did the following day). In essence, I was forced to “resect” my fingernail in order to drain the contained blood and serum. Thankfully, we don’t have to bear our weight on our phalanges.

FIGURE 1. Upward displacement of the toe results in downward displacement of the heels. The bones don’t rotate.

At this point I realized that if I were to have radiographed my finger — with a marker placed on the nail wall while placing considerable downward pressure on the tip of the finger — it would appear that the bone in my finger was rotating away from the nail. I knew full well that there was no possible way that the bone in my finger was moving. It would have to mean that, in fact, the fingernail was displacing upward as its connection to my nail bed was lost. The nail was moving, not the bone.

Why then are we so quick to use the phrase “rotation of the coffin bone” when we refer to laminitic horses? While my proposal to change the terminology is a reversal of conventional thinking, the treatment of the laminitic horse isn’t being questioned. Instead, if anything it is being verified and justified.

Alternative Viewpoint

However, by viewing the pathology from this alternative point of view, we can more easily set a treatment protocol by applying the concept of ground reaction forces to the laminitic hoof. I do not buy into shoeing fads, so I prefer to base my work on facts. There are no magic shoes or trims, just those that work. I am not going to tell you about some mysterious, cure-all way to shoe a horse. Rather, I’m going to present my research and some ideas that I have found useful.

Shoeing to modify ground reaction forces is a sound modality that is easily identified and proven. As such, I don’t care what shoe you use to accomplish the goal. I’m asking for understanding of the how and why, not the what.

It is also important to note that, historically, whenever we take a lateral radiograph of a hoof, it is at least partially weight bearing. If we were able to instead radiograph the distal limb out of weight bearing (which would lessen the degree of upward displacement of the hoof capsule), we would see that the bony column was in fact straight and that the illusion of bone rotation was being caused through movement of the hoof capsule when loaded.

In addition, make certain that any radiographs that are taken have markers on both the dorsal wall and frog. It doesn’t matter where the marker is placed on the frog as long as both you and veterinarian know exactly where it was placed.

Getting A Closer Look

To get a better idea of this, I have to thank Allie Hayes at Horse Science-Horse Sense for allowing me to use some of her photographs of both acutely and chronically laminitic hoof models. The concepts I am describing here and using her models to illustrate are based on my research and don’t necessarily reflect her views on laminitis.

FIGURE 4. This is an acutely laminitic hoof in which the bony column has maintained alignment. However the relative displacement of the hoof capsule was severe enough that the tip of P3 has prolapsed through the sole.

FIGURE 3. In this acutely laminitic foot, the bony column alignment hasn’t changed, but the distance from the dorsal wall to the dorsal edge of P3 has.

FIGURE 2. This normal hoof has uniform hoof wall thickness. Note the spatial relationship of the bony column to the hoof wall.

As these limbs are no longer attached to the horse, they clearly show that in the absence of weight bearing, only the hoof capsule is affected, not the angle of the bone.

The first specimen (Figure 2) is of a ”normal” hoof. Note the uniform thickness of hoof wall, but more importantly the apparent spatial relationship of the bony column to the hoof wall. If we don’t know what normal looks like, we can never hope to recognize abnormal. Too many of us cannot identify important structures within the hoof, nor can we properly read radiographs. As with forging, you need to practice, ask for help and stick with it. Without a working knowledge of basic anatomy we are merely shoeing hooves and not horses.

This second example (Figure 3) is an acutely laminitic hoof. There is hardly any difference in the alignment of the bony column, but there is a difference in the distance from the dorsal wall to the dorsal border of P3. The hoof wall has displaced upward. The bone has not rotated.

Next (Figure 4) is a much more severe case, but the bony column is still perfectly aligned. However, the relative displacement of the hoof capsule was enough to allow the coffin bone to prolapse clear through the sole.

Next (Figure 5) we have a case of chronic laminitis. The bony column is perfectly aligned, however owner neglect, unskilled farriery or simply ignorance has allowed the hoof capsule to severely displace. If a horse like this were referred to my practice, we’d have taken radiographs and a long trimming session would have ensued. You’d be amazed with feet like this what a difference you can make via trimming alone.

FIGURE 7. While this hoof may appear to show rotation of P3, the author points out that the tip of P3 shows significant bone loss and the hoof also displays many other pathologies that indicate this is a chronically foundered and poorly managed hoof.

FIGURE 6. Another example of chronic laminitis, displaying severe upward displacement of the hoof capsule.

FIGURE 5. This is a case of chronic laminitis. Note that the bony column remains perfectly aligned, however the hoof capsule is displaced.

Being conservative is essential in cases like this, as the excessively long hoof wall can be hyper vascular. This means it can develop a blood supply which an aggressive farrier might get into, causing serious bleeding. I have never encountered such a case, but I’m always one to err of the side of caution. Nippers are essential; a hacksaw isn’t.

In Figure 6, we have another chronically laminitic hoof. We still have alignment of the bony column, but there is severe upward displacement of the hoof capsule. In this case, it would appear someone did use a hacksaw to shorten the toe.

I know what you’re thinking after looking at Figure 7; that it “clearly” shows the rotation of the coffin bone. But take a closer look at the tip of P3. There is a lot of bone loss in this hoof. Also look at the color, thickness and consistency of the extensor tendon, as well as the shape of the navicular bone. Most importantly, look at the distal interphalangeal joint capsule spacing and note the dorsal hoof wall.

This is not a fair example and should not be compared to the other photos. At this point with this hoof, we aren’t just looking at upward displacement. This shows several different pathologies and would be — in my opinion — a terminal situation. There is significant damage to the common digital extensor tendon, as well as the bone loss and upward displacement of the hoof capsule.

The bone in this case would like to fall out of the hoof from probable sepsis of the joint capsule and erosion of the tendon. The hoof capsule appears to be beginning to slough off. There is nothing you can do for a horse like this other than bury it. This article is focused on horses we can help. Once there is significant bone loss and necrosis of tendons, it is another game entirely.

An Ethical Dilemma

The Figure 7 example is a chronically foundered and poorly managed hoof. This image does bring up the ethical topic of how far we should push the horse and owner. When you see a hoof that looks like this in radiographs, should the veterinarian even mention corrective shoeing to the owner? Should a farrier work on this horse knowing that the outcome is almost always death? Is it fair to the owner? What about the horse? Once there is bone loss it doesn’t come back. This horse will never be sound.

More Visual Comparisons

The next group of images (Figure 8) are examples of horses with acute laminitis. There is no evidence of bone rotation in any of the photos, just upward displacement of the hoof capsule. Most show remodeling of the tip of the coffin bone.

FIGURE 8. These are more examples of acute laminitis. Again, there is no evidence of bone rotation, but there is upward displacement of the hoof capsule. Most show remodeling of the tip of P3.

In Figure 9, we are looking at more cases of chronic laminitis. While there may be bone loss and severe remodeling of the coffin bone, the bony column is in alignment. Even in a chronic state, there is no bone rotation.

A Realistic Approach Is Needed

There is only so much you can do in laminitis cases. The owner must be realistic both financially and emotionally. If the horse owner can barely afford hay or grain, he or she certainly can’t afford to have you shoe the horse every 4 weeks and get new radiographs each time. If owners are so emotionally invested that every time the horse flinches, they start crying and beg you to stop because you’re hurting their baby; you’re not going to be able to do much.

FIGURE 9. These are more examples of chronically laminitic hooves. Despite severe coffin bone remodeling, there is no bone rotation.

And there really is only so much you can do. Some horses respond really well, and quickly. Others take months or years and never fully recover. To borrow a saying from a friend of mine, some things are, “outside my circle of influence!”

Expect Setbacks.

Owners also need to be encouraged not to lose faith if lameness returns after a period of seemingly great improvement. It is not uncommon for abscesses to occur 3 to 6 months after the acute phase has passed. Once through this period, things often look up rather quickly. Unfortunately, these setbacks often lead owners to euthanize an animal, contributing to elevated failure rates.

As the hoof wall at the toe displaces upward, the hoof will actually stretch (elongate) at the toe (Figure 10). We would not see this if the bone were merely rotating. This stretching is why — after a period of time — we run into the distended laminae at the toe. We see excessive heel growth for a couple of reasons, but mainly due to downward displacement of the hoof capsule caudally.

Note that the heels don’t really grow at an accelerated rate. They simply grow faster than the toe due to the compromised blood supply at the toe. All of the upward displacement of the coffin bone has to be judged as occurring around the center of articulation of the coffin joint.

FIGURE 10. As the hoof wall at the toe displaces upward, the hoof will actually stretch at the toe. The heel will grow faster than the toe because the heels get a better blood supply.

The circumflex artery relates to hoof growth at the toe, but the hoof has a secondary blood supply that nourishes the caudal portion of the hoof supplied by the paracuneal artery. This artery as of yet appears to be unaffected by laminitis.

In a similar vein, the need to ease the strain on the deep digital flexor tendon (DDFT) is not due to any increase in tension on the DDFT. What we want to do is ease the normal tension on the DDFT in order to minimize the lamellar tearing at the toe. We are not remedying a lesion in the DDFT, but rather creating an imbalance through trimming and shoeing in order to correct the more severe issue in the laminae.

Ground Reaction Force Principles

Ground Reaction Force (GRF) as it applies to farriery can be defined as the forces reacting with the hoof as it acts on the ground. These forces are equal and opposite of one another. The greater the web width of the shoe, the greater the GRF and vice versa. Remember we are talking about the width, not the thickness of shoe. Thickness of shoe stock has no bearing on GRF. Also realize that increased wearability of the shoe relates to width and not thickness as well.

There are two major principles of GRF modification.

1. Increase GRF when treating soft tissue lesions. An increase in GRF increases flotation of the shoe over soft ground and thereby prevents elongation of soft tissue (tendons and ligaments) that increases compression of joint capsule spacing.

2. Decrease GRF when treating bony lesions. A decrease in GRF allows penetration into soft ground, thereby allowing elongation of soft tissue (tendons and ligaments) that decreases compression of joint capsule spacing.

Soft tissue lesions will, over time, ossify and develop into bony lesions.

GRF Principles And Laminitis

So how do we apply GFR principles to the treatment of laminitis? First, it’s important to understand what is occurring.

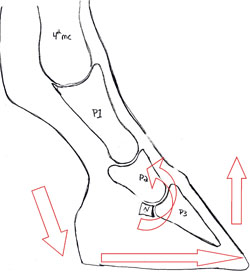

- In laminitis, the dorsal hoof wall and the dorsal border of the coffin bone are suffering from a compromised attachment. These are both bony lesions. As such, we want to decrease GRF at the site of the lesion. We can do this by narrowing the shoe’s web width at the toe.

- The DDFT’s normal force on the coffin bone is increasing the separation of the laminae at the toe. This is a soft tissue issue and therefore we want to increase GRF at the site of the lesion. (Remember that it inserts at the semi-lunar crest of the coffin bone.) So we want to widen either the width of web of the shoe at the heels, or provide another means to do that.

Dave Duckett’s Contributions

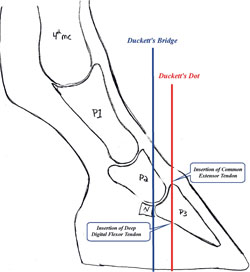

Duckett’s Dot and Duckett’s Bridge (Figure 11), first identified by farrier David Duckett, can be viewed as the foundation for most every shoeing or trimming modality around today. Duckett’s principles give us an unchanging set of landmarks by which to evaluate every hoof, regardless of breed, age, pathology or discipline.

Duckett’s Dot: This is an imaginary dot located approximately 3/8 inch behind the point of the trimmed frog that locates the center of P3. If a hole were drilled through this point, it would bisect P3 from the semi-lunar crest (the attachment location of the DDFT), to the extensor process (the attachment location of the extensor tendon). The Dot indicates the location of the center of mass of the coffin bone (center of weight-bearing when the limb is loaded).

FIGURE 11. This diagram shows the location of Duckett’s Dot and Duckett’s bridge, important landmarks that can be used to guide trimming and shoeing.

Duckett’s Bridge: This is another imaginary location, indicating the center of articulation of the coffin joint (distal interphalangeal joint). It occurs somewhere between 3/4 to 1 inch behind Duckett’s Dot. This is seen as the center point of a well-trimmed and shod hoof.

Ideally, the measurement from the toe to the bridge should be equal to the measurement from the bridge to the heel bulbs. Radiographically, this would be directly below the center of rotation of the distal end of P2 and directly below the junction of the navicular bone (distal sesamoid) and P3. Dave Farmilo, an Australian farrier makes a tool called the Dave Farmilo’s Hoof-Line that can be of a huge assistance here.

Burney Chapman And The Heart Bar

The late Burney Chapman is credited with reintroducing the heart bar shoe after finding it in Dollar and Wheatley’s A Handbook of Horseshoeing. However, this book does not specifically indicate the heart bar should be used for laminitis. In fact, the shoes that it does indicate for laminitis are very different than the heart bar and are — by GRF standards — useless.

Chapman actually deserves more credit than he’s typically given, because he didn’t simply open the book and have a ready-made answer. Instead, he applied a shoeing protocol for one type of pathology to another with great success.

The reason the heart bar has enjoyed such great success, at least in the hands of those skilled enough to use it, is that it fulfills the requirements of ground reaction force modification for a horse suffering from upward displacement of the hoof capsule. Simply stated, there is more metal and more shoe distal of Duckett’s Dot than there is forward of it.

In essence, it decreases GRF at the toe, allowing the hoof capsule at the toe to penetrate into soft ground, while increasing GRF within the caudal region, allowing for flotation of that region. This helps to lessen the upward displacement of the toe, while reducing strain on the DDFT, thereby stabilizing the hoof capsule.

Non-Laminitic Displacement

It is worth mentioning that the hoof capsule can be displaced in a multitude of ways unrelated to laminitis. Upward displacement of the hoof wall at the toe almost always relates to laminitis (but can also be seen radiographically in club feet). Jim Poor, the Midland, Texas, farrier, has said that treatment of a club foot is the same as that of a laminitic hoof and I tend to agree with his assessment.

Downward displacement of the hoof capsule at the toe is also seen in cases of negative palmar angle. The hoof capsule can also be upwardly or downwardly displaced both medially and laterally. Again, the bones within the hoof capsule aren’t rotating, but rather the hoof capsule, due to trauma or imbalance, is remodeling around them.

Whenever there is displacement of the hoof capsule there will be unequal joint capsule spacing as well as tension shifts among soft tissue (tendons and ligaments) during weight bearing.

Other Laminitic Treatments

The heart bar shoe is by no means the only treatment for laminitis. With the advent of new hoof pour and packing materials, it can be highly beneficial to use other means to support the caudal region of the hoof in laminitic horses. There are also different means of attaching a shoe to the hoof to consider.

Nailing provides a secure attachment of the shoe package to the hoof, but can be difficult due to the pain it causes for the horse. Glue-on shoes reduce the pain issue, but create their own problems since they can be difficult to keep on in some climate and weather conditions. The most beautiful, beneficial shoeing package in the world does no good when it is buried under 3 feet of mud.

The shoes developed by Rob Sigafoos and marketed through Sound Horse Technologies are quite beneficial if you are comfortable working with them (I’m speaking of the Series II with a treaded wedge plate being modified for a laminitic horse). In the future, I think we’ll be using more of these types of shoes than we will heart bar shoes.

Since most laminitic horses are placed on stall rest in stalls with deep bedding, the hooves are often subjected to wet, urine-soaked shavings. This can quickly lead to a product failure with most adhesives. I do not feel stall rest is necessary or warranted when pain medication is not being utilized. Pain is nature’s way of limiting the amount of movement the horse will attempt. Medicating a horse can create a dangerous situation. A tranquilized horse may feel better, overexert itself and create more trauma to its feet.

There is also no need to load the frog when the hoof is not weight bearing.

Types Of Frog Support

Active Frog Support: Active frog pressure (or support) is when the frog is always loaded, whether the foot is weight bearing or not. I like this form of frog pressure the least, as I feel it can do the most harm.

Passive Frog Support: Passive support of the frog means the frog is only loaded when the hoof is weight bearing. There are many ways to accomplish this:

- A frog plate that is parallel to the frog, but just shy of touching it when the hoof is unloaded. I’ve heard some people refer to this as having the frog plate “kissing” the frog.

- Using some sort of frog-support pad.

- Utilizing a hoof pour or impression material on the hoof.

It should be noted that when using either active or passive frog support, no pressure should be applied forward of Duckett’s Dot. If you use a rigid frog plate, the edge of the frog must be visible all the way around the plate. You don’t want to crush and destroy the circumflex artery. That artery already has issues. Don’t make more.

Also remember that you don’t need to create frog pressure as much as you need to support the caudal portion of the hoof.

And — if the horse is lying down — you don’t need frog pressure anyway.

What About The Toe?

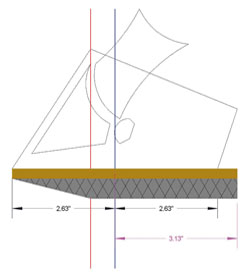

When shaping shoes for these horses, you can all but ignore the toe. You are shaping a symmetrical shoe to fit the caudal aspect of the hoof. It’s likely that you will be dressing back large amounts of dorsal toe wall, setting the toe of the shoe back and nailing behind the widest part of the hoof (Figure 12). So shape your shoe from the heels forward, and dress the toe off after clinching.

FIGURE 12. This diagram includes a rolled toe to ease breakover and added support for the caudal aspect of the hoof.

It’s also advisable to shape your shoes from heel to toe, rather than toe to heel.

Applying the principles of ground reaction forces doesn’t detract from the basic need for:

- Avoiding the creation of sole pressure at the toe.

- Placing your nail line in relation to the white line.

- Balancing the hoof capsule.

- Using the smallest size and number of nails necessary.

- Easing breakover as much as possible while still protecting the hoof. Consider large rolled toes or rocker toes or open toes, or maybe adding side breakover, etc. We want the hooves to breakover easily and where they want to breakover, not where we think they should.

Two Options To Consider

I’ve had success recently with a pair of shoeing options.

First is a narrow-webbed half-shoe, (in the case of Figure 13, a St. Croix 000 Lite Rim) attached to a Grand Circuit Flapper pad. I apply impression material under the pad from approximately Duckett’s Dot to the heel.

This particular shoe would then fit a 0 sized hoof. The narrow web of the toe would allow ground penetration, while the pad would prevent the caudal portion from penetrating the ground through increased floatation. Between the pad and the impression material, you have provided passive frog support. The increased floatation of the caudal aspect will also have the benefit of increasing the height of the heels in soft ground, in weight-bearing, with about a 2-degree lift.

FIGURE 13. This shoeing treatment includes a St. Croix Lite Rim shoe and Grand Circuit Flapper pad.

This shoeing package has helped horses I have used it on, but there is a possibility of sole pressure created by the rigid front of the pad which, in most cases, would be forward of Duckett’s Dot.

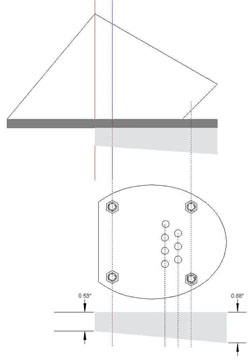

A new idea that I’ve been kicking around is to fit the hoof with the narrowest webbed shoe that I can find. I’ll fit the shoe to the hoof and mark the location of the Dot and the Bridge on a branch. Going back to my drill press, I’ll drill and tap four holes to receive a modified aluminum wedge hospital plate (Figure 14). I’ll then drill holes in the plate over the frog to hold my impression material.

Unlike a traditional hospital plate, this one only attaches to the shoe from about the widest point back, leaving the toe uncovered.

Conclusion

I’m not going to suggest a particular shoe, pad or packing for treatment. I’m not going to suggest that we can go out and fix every horse with a problem. What I am asking is that you look at these problems from another point of a view. Think outside the box.

FIGURE 14. This shoeing treatment involves a narrow webbed shoe combined with a modified aluminum wedge hospital plate that would attach only from the widest part of the shoe back. Impression material would be placed over the frog.

While this article, hopefully, proved to some of you that bones can’t and don’t rotate, others will disagree and probably send me hate mail. I’m not saying that I’m right and everyone else is wrong. Instead I am merely suggesting that by approaching laminitis from the point of view that the hoof capsule is moving rather than the coffin bone rotating, makes shoeing protocols easier to access.

If people didn’t stop and question the conventional norm, the world would still be flat, and the Earth would still be the center of the universe. Don’t be afraid to have an opinion, just be ready to back it up.

Finally, a good permanent marker is an invaluable shoeing tool. Don’t just trust your eye. Mark the hoof structures important to your shoeing methods. Make corresponding marks on the shoe. Think of it as measure twice, nail once! Also try to take digital photographs of the radiographs so you can always have them handy.

Post a comment

Report Abusive Comment