It wasn’t that long ago that a diagnosis of Cushing’s disease — Pituitary Pars Intermedia Dysfunction (PPID) — was felt to mean the horse had less than 5 years to live. The cause of the laminitis in these horses was poorly understood and, therefore, poorly managed. We know better now.

The Equine Cushing’s and Insulin Resistance Group was founded in 1999 by an owner with an atypical Cushing’s mare who wanted to promote the dissemination of correct scientific information. We have followed the research closely, as well as thousands of cases. I can’t think of any situation where it’s more critical for owner, veterinarian and hoof-care professional to be fully informed and working together than in laminitis care.

Defining Acute

We often describe the newly diagnosed laminitic horse as “acute.” What does acute laminitis mean?

With the possible exception of laminitis of pregnancy, few endocrinopathic laminitis (EL) cases are truly acute, where acute means the day before they were normal and the next they were in obvious laminitis. With endocrinopathy, laminitis can be the culminating event at the end of a long road.

It has been 20 years since P.J. Johnson first described occult changes to the laminae of horses with insulin resistance (IR), meaning no obvious clinical symptoms or none reported. Originally ascribed to cortisol excess (pre-Cushing’s; peripheral Cushing’s), this form of laminitis is now understood to be an insulin effect.

“We believe that conditions associated with glucocorticoid (GC) excess (exogenous or endogenous) and IR lead to structural changes in the connective tissues of the hoof-lamellar junctional zone that might be viewed simplistically as a ‘weakening’ effect on the attachment interface. Over time, these changes result in lengthening and attenuation of the primary and secondary dermal lamellae, not necessarily associated with pain, inflammation, or lameness per se.” (Johnson et al. 2004)

When we look under a microscope, whether 24-48 hours after insulin infusion or 3 years into a painful history, the changes in the feet are identical. Variations may apply, with changes once a laminar wedge is apparent, but the basic underlying histopathology of the laminae is the same, whether acute or chronic and whether the horse is in pain.

Takeaways

- The basic underlying histopathology of the laminae remains the same after insulin infusion, regardless of whether it’s acute or chronic.

- The keys to success is to get and keep insulin and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) controlled, with normal levels being the goal for ACTH and as close to normal for insulin.

- The ultimate goal in a healthy hoof is approximately equal distance from the coffin bone to the ground, the edge of the coffin bone to the hoof wall and the tip of the coffin bone to the tip of the toe.

These changes are seen in both symptomatic and asymptomatic horses, in chronic cases, as well as within 48 hours of insulin infusion. Sudden onset is not so sudden after all. It is not an acute problem and it did not just happen. If you are going to successfully attack it, you have to look for the cause via a detailed history.

Signs of Occult Laminitis in the Foot

Early signs can be seen in horses that are not recognized as lame.

- Stretching in the white line.

- Hemorrhage in the white line.

- Dropped/flat soles; thin soles.

- Possibly “rings” in the hoof wall.

The above changes are even more obvious in overgrown feet with long toes. They do not happen overnight.

Signs of Occult or Sub-Acute Laminitis in the Horse

- A stilted, wooden gait: the horse is stiff.

- Rigid head carriage at the walk.

- Less spontaneous movement.

- Reluctance to trot.

- Reluctance to make sharp turns.

- Hesitant on hard ground.

- Tension through shoulders, back and hind quarters.

- Social status will drop when in pain.

- Pain and signs will disappear with blocking of the feet.

Owners are often unaware of an issue because pain is symmetrical — the horse does not limp and there is no head bob. A horse may be more stoic about pain that builds insidiously and the animal is often valued as unusually quiet or gentle.

What Drives Endocrinopathic Laminitis?

It all boils down to insulin. Approximately 90% of horses being seen for lameness caused by laminitis have an endocrinopathy as the cause — either Equine Metabolic Syndrome (EMS) or PPID. (Karikoski et al. 2011) More specifically, studies such as Coleman, et al. 2018 and Menzies-Gow et al. 2017, have identified hyperinsulinemia as the risk factor for pasture laminitis.

Hays with hydrolyzable carbohydrates (HC) — ethanol soluble carbohydrates (ESC) plus starch — over 10% can also precipitate laminitis in susceptible horses. Laminitis has been induced in both clinically normal horses and ponies by hyperinsulinemic, normoglycemic conditions under insulin infusion. In PPID, the excessive levels of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and other pituitary hormones create IR or worsen it if already there.

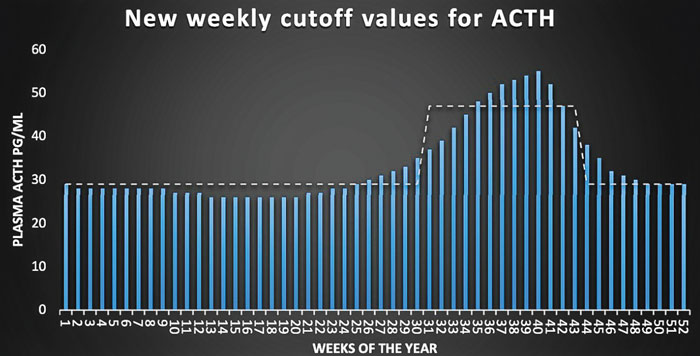

Bars represent adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) cutoff values for every week of the year (Durham 2016, unpublished data) with the dashed line indicating previously used monthly cutoff values (Copas and Durham, 2012).

The key to success is to get and keep insulin and ACTH controlled, with normal levels being the goal for ACTH and as close to normal as possible for insulin.

Triggers of Acute Worsening

Diagnosis often is only made when lameness worsens as a result of increasing hyperinsulinemia from some precipitating event such as the following.

PPID seasonal rise. Uncontrolled PPID or exaggerated seasonal rise can drive insulin higher. Liphook Equine Hospital in the United Kingdom tested more than 30,000 horses, both PPID and normal, to establish weekly normal cutoffs of ACTH values throughout the year. Because the above chart is unpublished data, age distribution is unknown. Lee et al. 2010, also in the U.K., found that older, non-PPID horses might have a higher seasonal rise than young horses. An older horse may go as high as 80 or 90 in the fall and still not be PPID.

Dietary indiscretion. Hay, pasture, feeds, or even treats with HC (simple sugar plus starch) levels high enough to cause a significant insulin spike, generally ESC and starch over 10%.

Cold. EL has a strong vascular component, regardless of what else might be occurring histologically. In other species, sudden cold snaps can cause hormonal changes, with higher insulin as a common response. Acute pain response can occur either after a sudden dramatic drop in temperature or persist all season long, when temps go below a critical level, e.g., 40 degrees Fahrenheit.

Abnormal ovarian activity. In the mare, abnormal ovarian activity has features similar to polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) in human females and may occur during spring transition (March in the northern hemisphere), or all year long. The crest increases and laminitis occurs when the mare shows estrus. Severe flank pain is common to the point where it is diagnosed as colic. Irregular cycling and a prolonged interovulatory interval also occur.

New Weapons in the War Against Insulin — SGLT2 Inhibitors

Despite our best efforts with diet control, metformin and pergolide, some horses do not come under good insulin regulation and continue to be laminitic. This is often, but not always, horses with PPID and in some cases they are diabetic with abnormal blood sugar. Fortunately, we have another option.

SGLT2 is the acronym for sodium-glucose cotransporter 2. This cellular transporter is most active in the kidney where it serves to take glucose from the filtered blood and return it to the body. The two drugs blocking this that have been used in horses are canagliflozin/Invokana and ertugliflozin/Steglatro. By blocking reuptake, the glucose load on the body is greatly reduced and insulin drops (Kellon and Gustafson, Sundra).

The degree of insulin improvement varies from normalized to barely changed but interestingly there is virtually 100% improvement in laminitis pain. Decreased kidney function from the resulting increased urine output and urinary tract infections are potential complications but have not been seen to date. Horses should be given generous amounts of salt in their feed or sprinkled on moistened hay to keep them drinking well.

The major side-effect is elevated levels of triglycerides. This occurs because of the energy crisis created by the glucose loss. Increases are also seen naturally with fasting or after exercise. If uncontrolled, it can lead to liver enzyme elevations (Kellon EM and Gustafson KM). This is addressed by feeding free choice, unsoaked hay with hydrolyzable carbohydrates up to 12% and 1 lb. beet pulp per 500 lbs. of body weight daily. Beet pulp produces primarily acetate when fermented. Acetate can substitute for glucose in energy pathways.

Drugs That Can Affect Laminitis

Phenothiazines. Suppresses dopamine production and increases insulin with acute exposure. It’s found in acepromazine and some dewormers.

Xylazine. Reduced insulin and hyperglycemia followed by reactive compensatory insulin surge.

Sulfa antibiotics. Increased insulin secretion.

Praziquantel. Hyperglycemia is caused by reduced peripheral glucose utilization. The response to high blood sugar will be an insulin surge.

Corticosteroids. Induces insulin resistance.

Dormosedan/Tobugesic. Produces the same effects as Xylazine.

Third generation Cephalosporins (Excenel, Excede, Naxcel). Severe laminitis.

Vaccination. Owners and veterinarians swear vaccinations can cause laminitis; however, the mechanism and timing are questionable and cannot be reproduced experimentally. In any other species, an individual with a severe reaction would never be vaccinated again. Because there might be an increased risk of laminitis, use only core vaccines and consider titers, which is the highest dilution yielding a positive reading. Reactors should not be revaccinated.

Twenty-year-old Grits has returned to the show ring after recovering from PPID, insulin resistance and laminitis. Photo by: ECIR

Differential Diagnosis

Personally observed conditions initially misdiagnosed as laminitis include the following.

- Colic (stretched out stance).

- Tying-up (pain, refusal to move, tight muscles).

- Acute neurological disease (EPM) (distress, reluctance to move because of ataxia).

- Bilateral coffin bone fractures.

- Other causes of front foot lameness include deep digital flexor tendon pathology (heel pain syndrome), navicular disease, trim issues and hoof abscess, especially if the pain is obviously worse in one foot.

- Low-grade laminitis pain is frequently misdiagnosed as hock lameness due to posture, weight transfer behind at rest and in motion and shortened stride in a rush to unload the front feet.

Effective Approach to Acute Care

Everyone’s first instinct is to reach for phenylbutazone or another non-steroidal anti-inflammatory (NSAID) medication to control pain but these are minimally effective. The reason is that endocrinopathic laminitis is not inflammatory and these drugs do not control insulin.

McGowan and Patterson-Kane’s 2017 literature review reported there is minimal neutrophil infiltration in endocrinopathic laminitis. Storms et al. 2022 described increased myeloperoxidase activity, presumably from neutrophils, in the laminae of horses subjected to a 48-hour euglycemic hyperinsulinemic clamp but didn’t test tissues until the 48-hour mark, when damage is already done. They would have been looking at a clean-up response, not the cause.

Matrix metalloproteinase enzyme activation and basement membrane pathology are heavily publicized components of other forms of laminitis, like fructan or grain overload, but there is little to no evidence of this in endocrinopathic laminitis (Patterson-Kane et al. 2018).

Any inflammation in endocrinopathic laminitis is a secondary response to tissue damage, not the cause. NSAIDs shouldn’t be used for longer than 5 days, but horses often are on a prolonged course because the insulin level and trim haven't been adequately addressed.

An acronym I use to describe a comprehensive approach is DDT.

D: Diagnosis.

D: Diet and drugs.

T: Trim.

Diagnosis

When seeking an accurate diagnosis, look at the whole horse not just its lameness or seeming lack thereof.

Consider attitude, posture, movement on hard vs. soft ground, external hoof changes, status in the herd and, when suspicion arises, always do nerve blocks.

Laminitis is a sign, not a disease, and has many causes. If the horse has not been tested for EMS and PPID with insulin and ACTH, this can be done after the condition has stabilized. Acute pain has been shown to induce insulin resistance in humans (Greisen et al. 2001) via cortisol release, but Gehlen et al. 2020 showed up to moderate pain does not influence ACTH, so complete pain relief isn’t necessary before testing. In the meantime, starting metformin at 30 mg/kg twice a day can help control insulin. If the horse also has PPID, pergolide will be necessary to lower insulin.

Diet & Drugs

As above, a short course of NSAIDs during the clean-up phase, with metformin to assist in insulin control, is indicated. If PPID is strongly suspected, a trial of pergolide is reasonable. Remember that horses in their teens may have fall onset laminitis as the first sign of PPID with no other external indicators (Donaldson 2004). Suspect this if unexplained fall laminitis is the first episode of laminitis in the horse’s life.

The emergency diet should be soaked grass hay only, fed at 1.5% of current body weight or 2% of ideal weight, whichever is larger. Plain beet pulp, which has been well-rinsed and then soaked, can be used to carry supplements and medications. No pasture, alfalfa, or clover. No grains, including those that claim to be safe and no balancers, since their base is often not safe. Safe means a focus on hydrolyzable carbohydrates — less than 10% simple sugar (ESC) and starch combined.

Learn More Online

- For detailed information about comprehensive care of acute endocrinopathic laminitis, visit the Equine Cushing’s and Insulin Resistance Group website.

- Peruse free NO Laminitis Conference proceedings at ECIR Group case chronicles under the tab at the top of the page.

- Download the instructions for a realigning trim.

- Read, “Clinical Outcome of 14 Obese, Laminitic Horses Managed with the Same Rehabilitation Protocol.”

It is not unusual to see pain drastically improve within 2 to 3 days when an appropriate diet is started, even if NSAIDs are discontinued.

A general vitamin and mineral supplement can be added but it is far better to have the hay analyzed so that one can be chosen that matches what the horse needs. Also, analyze for sugar and starch to see whether soaking to lower should continue. Vitamin E, 2000 IU for the average size horse and 4 to 6 oz. of ground flax should be added, as well as 1-2 weighed oz. of salt. After the hay is analyzed, supplementation of vitamins and minerals with correct ratios to match the hay should be done (Kellon 2007).

Trim

Getting and maintaining appropriate hoof trimming is often the most difficult challenge for owners of these horses. Whether barefoot or in a device, a realigning trim is essential for good results and healing to begin, as described in the instructions for the Steward Clog, as well as Taylor et al. 2014, both can be found by clicking here.

Cupcake was diagnosed with PPID and Cushing’s disease in 2013. Owner Carla Peters followed the ECIR protocol to reduce the insulin resistance numbers and Cupcake is doing well. Photo by: Carla Peters

The feet should be radiographed as soon as possible. The ultimate goal in a healthy hoof is approximately equal distance from the coffin bone to the ground, the edge of the coffin bone to the hoof wall and the tip of the coffin bone to the tip of the toe — all on lateral radiographs. The most common trimming error are long toes, putting significant leverage on weakened laminae during breakover, and underrun heels, reducing the shock-absorbing capacity of the hindfoot, frog and digital cushion.

To correctly realign bones and soft tissue within the hoof capsule, remove shoes and trim the horse to have a short, rounded toe and palmar angle no higher than 5 degrees to minimize stress to the laminae. The walls should be unloaded by beveling and heels brought back to the widest part of the frog if there is sufficient foot to do this. Otherwise, the heels can be ramped.

Styrofoam blocks or boots and pads are best for comfort in the acute phase when growth is often accelerated and requires frequent trims, often as much as every 2 weeks.

If you focus on diagnosis, diet, and trim — not just pain control — the outcome will be much improved.

References

- Coleman MC, Belknap JK, Eades SC, Galantino-Homer HL, Hunt RJ, Geor RJ, McCue ME, McIlwraith CW, Moore RM, Peroni JF, Townsend HG, White NA, Cummings KJ, Ivan-Miojevic R, Cohen ND. Case-control study of risk factors for pasture-and endocrinopathy-associated laminitis in North American horses. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2018 Aug 15;253(4):470-478. doi:2460/javma.253.4.470. PMID: 30058970. https://avmajournals.avma.org/view/journals/javma/253/4/javma.253.4.470.xml

- Copas VEN, Durham A. Circannual variation in plasma adrenocorticotropic hormone concentrations in the UK in normal horses and ponies, and those with pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction. Equine Vet J. 2012 Jul;44(4):440-3. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-3306.2011.00444.x. Epub 2011 Aug 18. https://beva.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.2042-3306.2011.00444.x

- Donaldson MT, Jorgensen AJ, Beech J. Evaluation of suspected pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction in horses with laminitis. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2004 Apr 1;224(7):1123-7. doi: 10.2460 javma.2004.224.1123. PMID: 15074858. https://avmajournals.avma.org/view/journals/javma/224/7/javma.2004.224.1123.xml

- Durham AE. Seasonal Changes in ACTH Secretion The Liphook Equine Hospital Laboratory, Liphook, GU30 7JG.https://liphookequinehospital.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/Seasonal-Changes-in-ACTH-Secretion2.pdf

- Gehlen H, Jaburg N, Merle R, Winter J. Can Endocrine Dysfunction Be Reliably Tested in Aged Horses That Are Experiencing Pain? Animals (Basel). 2020 Aug 14;10(8):1426. doi: 10.3390/ani10081426. PMID: 32824027; PMCID: PMC7459856. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7459856/

- Greisen J, Juhl CB, Grøfte T, Vilstrup H, Jensen TS, Schmitz O. Acute pain induces insulin resistance in humans. Anesthesiology. 2001 Sep;95(3):578-84. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200109000-00007. PMID: 11575527. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7459856/

- Johnson PJ, Messer NT, Slight SH, Wiedmeyer C, Buff P, Ganjam VK. Endocrinopathic laminitis in the horse. Clin. Tech. Eq. Prac. March 2004, Vol 3, No 1. https://files.cercomp.ufg.br/weby/up/66/o/laminite_eq_endocrino.pdf

- Karikoski NP, Horn I, McGowan TW, McGowan CM. The prevalence of endocrinopathic laminitis among horses presented for laminitis at a first-opinion/referral equine hospital. Domest Anim Endocrinol. 2011 Oct;41(3):111-7. doi: 10.1016/j.domaniend.2011.05.004. Epub 2011 Jun 7. PMID: 21696910. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0739724011000737?via%3Dihub

- Kellon, E. Diseases Leading to Laminitis and the Medical Management of the Laminitic Horse. Equine Podiatry. St. Louis: Saunders. 2007.

- Kellon EM, Gustafson KM. Use of the SGLT2 inhibitor canagliflozin for control of refractory equine hyperinsulinemia and laminitis. Open Vet J. 2022 Jul-Aug;12(4):511-518. doi: 10.5455/OVJ.2022.v12.i4.14. Epub 2022 Aug 7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9473365/

- Kellon EM, Gustafson KM. Hypertriglyceridemia in equines with refractory hyperinsulinemia treated with SGLT2 inhibitors. Open Vet J. 2023 Mar; 13(3): 365–375. doi: 10.5455/OVJ.2023.v13.i3.14 Epub 2023 Mar 20. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10072834/

- Lee Z, Zylstra R, Haricot S, The use of adrenocorticotrophic hormone as a potential biomarker of pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction in horses. The Veterinary Journal Vol 185, Issue 1, July 2010, Pages 58-61 doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2010.04.014. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S109002331000122X?via%3Dihub

- McGowan C, Patterson-Kane J. Chapter 10: Experimental models of laminitis: hyperinsulinemia. In: Belknap JK, Geor R. editors. Equine Laminitis. Ames, Iowa: Wiley Blackwell; (2017). p. 68–74. 10.1002/9781119169239.ch10

- Menzies-Gow NJ, Harris PA, Elliott J. Prospective cohort study evaluating risk factors for the development of pasture-associated laminitis in the United Kingdom. Equine Vet J. 2017 May;49(3):300-306. doi: 10.1111/evj.12606. Epub 2016 Aug 25. PMID: 27363591. https://beva.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/evj.12606

- Patterson-Kane JC, Karikoski NP, McGowan CM. Paradigm shifts in understanding equine laminitis. Vet J. 2018 Jan;231:33-40. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2017.11.011. Epub 2017 Nov 22. PMID: 29429485. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1090023317302290?via%3Dihub

- Storms N, Medina Torres C, Franck T, Sole Guitart A, de la Rebière G, Serteyn D. Presence of Myeloperoxidase in Lamellar Tissue of Horses Induced by an Euglycemic Hyperinsulinemic Clamp. Front Vet Sci. 2022 Mar 11;9:846835. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2022.846835. PMID: 35359667; PMCID: PMC8962398. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8962398/

- Sundra T, Kelly E, Rendle D. Preliminary observations on the use of ertugliflozin in the management of hyperinsulinaemia and laminitis in 51 horses: a case series. Equine. Vet. Educ. 2022;00:1–10. doi: 10.1111/eve.13738. https://www.abvp.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/2023-01-January-Equine-_Preliminary-observations-on-the-use-of-ertugliflozin.pdf

- Taylor D, Sperandeo A, Schumacher J, Passler T, Wooldridge A, Bell R, Cooper A, Guidry L, Matz-Creel H, Ramey I, Ramey P. Clinical Outcome of 14 Obese, Laminitic Horses Managed with the Same Rehabilitation Protocol. JEVS 2014 April Pages 556-564 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jevs.2013.10.003

Post a comment

Report Abusive Comment