American Farriers Journal

American Farriers Journal is the “hands-on” magazine for professional farriers, equine veterinarians and horse care product and service buyers.

All Photos by: Mike Bagley

The email arrived in Mike Bagley’s inbox on May 6, 2020. The horse owner, who didn’t know Bagley, inquired about whether the Canton, Ohio, farrier would take on her aged Standardbred gelding with white line disease

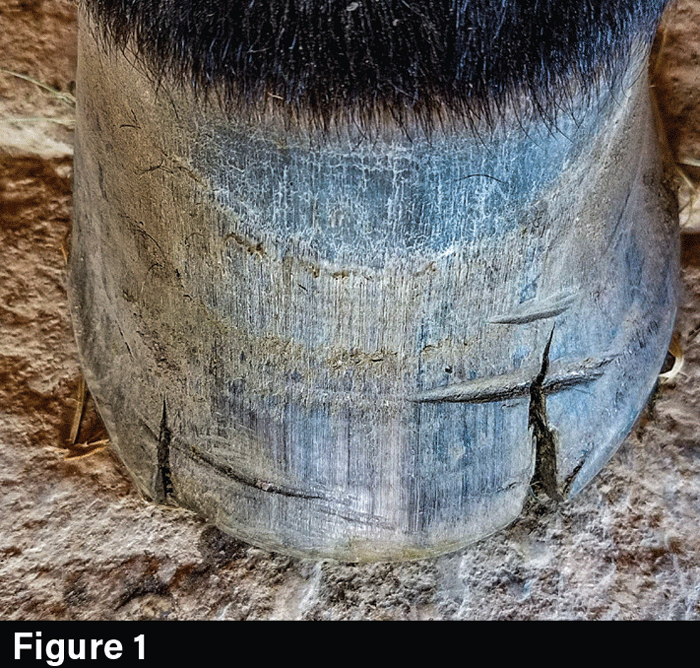

She provided photos of Andrae’s right front hoof, as well as contact information for her veterinarian. At a glance, it looked like the horse only had vertical cracks (Figure 1). The horse owner’s regular farrier didn’t realize the cracks indicated white line disease. However, radiographs revealed a large void in the hoof wall (Figure 2). White line disease had invaded at least halfway up the wall and the hoof had a thin sole. It turned out to be the second worst case of white line disease that Bagley has seen.

Andrae’s right front hoof presents with vertical cracks.

A radiograph indicates that white line disease invaded at least halfway up the hoof wall, as well as little sole depth.

“I called the vet and he said he believed I needed to resect a good amount of the hoof wall but that he wasn’t sure what it would entail,” says the vice president of the International Association of Professional Farriers. “I explained it to him. He agreed that sounded good and turned me loose.”

Bagley asked the vet if he would like to be there to perform a nerve block or to respond in case there was too much bleeding.

“The outcome was successful because of the teamwork between me, the veterinarian and…