What kind of horses are you shoeing?

It’s a question that we’ve all been asked. Perhaps some have answered, “Well, sport horses.” It’s a response I hear a lot, especially from younger farriers who are up and coming. But what does it mean?

Sport horse generally seems to mean that farriers are shoeing English horses that are hunters, jumpers, dressage and eventers. They all are grouped together, which is a pet peeve of mine.

We can rule out breeding stock, minis, retirees and pets as sport horses, but not many others. What about recreational horses? In some respects, trail riding horses have more demanded of them than many others. Some trail riding clients forget that they have a horse all winter. As the weather gets better in March, they pull out the horse and ride it for 8 hours. They tie it to a picket line, wake up the next morning and ride it for another 8 hours. We might not consider it a sport, but it’s definitely demanding on that horse.

The same can be said for some workhorses. Ranch geldings and road horses take a beating. When you think about it, there just aren’t many of them that aren’t sport horses.

The basic considerations that we’re looking at when shoeing a sport horse — no matter the sport -— are conformation and posture; judged vs. timed; footing and traction; length, weight and width; and ethics, support teams and financial constraints.

Farrier Takeaways

- “Sport horses” are generally considered hunters, jumpers, dressage and eventers; however, other disciplines — including recreational — also demand so much from the horse. “Sport” is an appropriate catch-all term because of the athletic demands placed on them.

- Understanding conformational limitations will inform you of how you can help a horse in its chosen discipline.

- Traction helps a horse with acceleration and deceleration, yet there is little that we are doing to increase the horse’s ability to accelerate. Almost everything we do is designed for deceleration.

1 Conformation and Posture

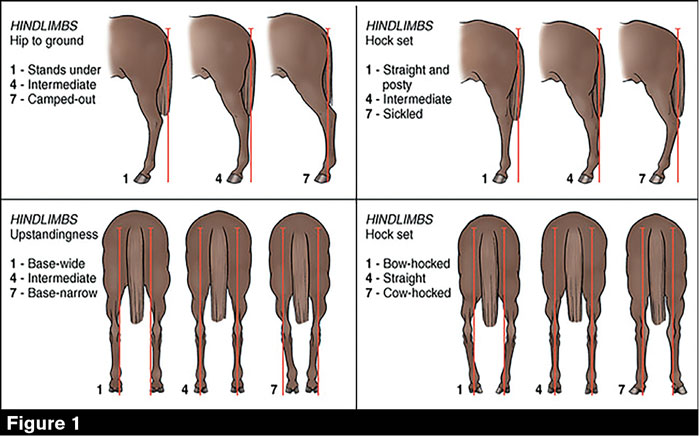

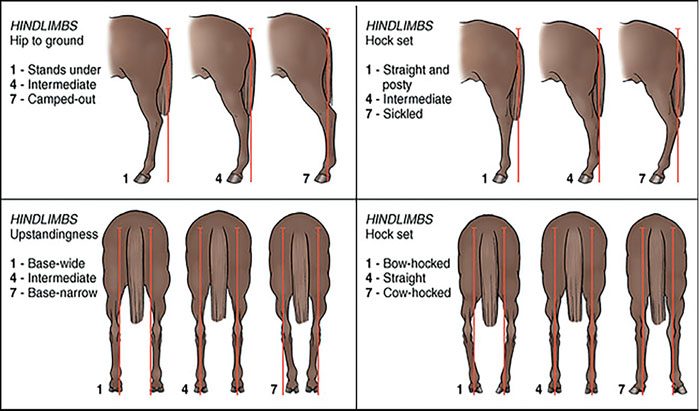

We don’t shoe many ideally conformed horses and must work around those constraints. If you look at conformations (Figure 1), you’ll recognize horses that you work on. Those conformation limits will hit you as you shoe these horses and will determine how far you can go with that horse. It’s important for us to understand this upfront so that we don’t overcommit.

Understanding conformation will help you determine the horse’s limits and how far you can go with shoeing for the discipline.

Forty years ago, I used to talk about fixing horses. I was convinced that I could fix horses, but it’s impossible. You must work within the limits and constraints that you have.

If a client goes past third-level dressage with a cow-hocked horse, that’s an amazing accomplishment. A different client might be OK with a cow-hocked horse in a cutting pen. It might benefit it. Knowing the discipline and the constraints that conformation places on that discipline are important. This understanding will keep you out of trouble.

When I first started shoeing decades ago, I didn’t see many high-low horses (Figure 2). Now, everything I see is high-low. I don’t consider that conformation; I consider it posture.

The severity of a high-low condition will place constraints on the horse in certain disciplines.

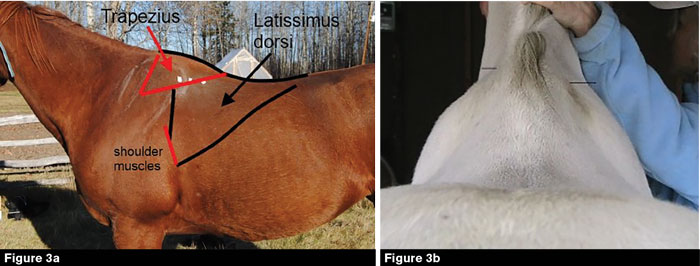

There are two main shoulder muscles that are important — the cervical trapezius and the latissimus dorsi (Figure 3a). The dominant low side of the cervical trapezius is often mistaken as being overly developed when it bulges in the withers (Figure 3b). The steep side often appears slaggy and flat. Trapezius muscles are flat. They’re not biceps. They are not bulging, bulky muscles. I don’t know that you’re looking at an overdeveloped muscle so much as you’re looking at postural issues.

The dominant low side of the cervical trapezius is often mistaken as being overly developed when it bulges in the withers. The steep side appears saggy and flat. Trapezius muscles are not bulging, bulky muscles. They are flat.

The high-low condition and how advanced it is will place constraints on you within certain disciplines more than others. If a client asks a dressage horse to do tempi changes and gets lead changes, then they’re not going to score high with a high-low horse. You can work with a high-low horse. You can try to work it around the condition. However, that posture is not conducive to scoring well and moving that horse beyond a third-level dressage horse.

The key concepts to keep in mind for conformation and posture are going to be soundness, suitability, longevity and commitment level. You have to look at it and say how well is this horse suited to stay sound, for how long and the commitment level?

I have several horses that are not suited to their discipline, but the owners’ acceptance of their horses’ limitations is such that it’s OK. “I love Fluffy. If he never makes it past second-level dressage or if he never jumps more than 2 feet or whatever, I’m OK with that.”

2 Judged Vs. Timed

This is a huge consideration. When you’re looking at these horses, it is much easier to shoe the timed horse than it is to shoe the judged horse. We have various disciplines: Hunters, jumpers, Western pleasure, barrel horses, polo ponies, dressage, hitch horses, racehorses, reiners, rope horses, cutters, endurance, equitation, eventers, vaulting and driving. But, if you break them down, the big consideration for the most part is whether you have a judge or a time clock.

In the judged events, where you have reiners, hunters and Western pleasure, you’re shoeing not as much for the horse as you are for the desired movement. That desired movement can vary from one day to the next or one judge to the next. It’s knowing what the judge is looking for, and playing the game is an important part. Whereas, in the timed events, you have a clock. You have the luxury and the opportunity to shoe more for the horse. That makes a huge difference in the way that we deal with these.

Farriers encounter key concepts of traditions, fads, personal preferences and the number of people involved. Tradition is huge. Fads, we often hear, “Oh, well this new shoe is going to cure this and everything since the beginning of time is thrown out the window.” The personal preferences of the judges and the number of people involved. Now you’ve got judges, owners and trainers, and you’re trying to please a lot of people other than just pleasing the horse.

3 Footing and Traction

Most of what we have read about in older, traditional literature and what we are trained to shoe early on is based on traditional footing, which is turf or sod. As a result, a lot of what we do is centered around the traditional footing. We transitioned to shoeing for modern footing for arenas and sand footing. We have transitioned again to contemporary footing and are shoeing for artificial surfaces. We also have horses that are working on another type of artificial footing, where we have concrete, tarmac or asphalt.

There are considerations we must look at for increasing the surface area of a shoe, minimizing penetration into a surface and so forth. Traction comes into play, as well as taking traction away.

One of the things that we fail to consider when looking at traction is that it has two purposes — it helps horses decelerate and accelerate. If you think about where we place traction in relation to the biomechanics and the function of the limb and the foot, there’s very little that we are doing to enhance or increase that horse’s ability to accelerate. Almost everything that we do is designed for deceleration.

The key concepts to keep in mind are soundness, flotation and penetration, the types of traction and its placement. Soundness is an important issue when you start applying traction. Everything is going to transfer through the points of articulation above the foot.

“You have the opportunity to shoe more for the horse that competes in timed events…”

When we think about that traction, it is about flotation and penetration. In some cases, we’re trying to keep the horse on top of the ground. In others, we’re trying to get it into the ground. Basically, there are two primary types of traction, which are either friction or penetration. A traditional caulk is going to create friction and drag, whereas a traditional wedge is going to penetrate.

It’s interesting when we put both of those types on the same foot. We’re asking one side of the foot to drag and slide and the other side to cut into the ground. That creates a tremendous amount of torque.

4 Length, Weight and Width

The limb is going to move to length, weight and width. If you look at a contemporary shoe display, what you see is maintaining stock dimension, as well as thickness and width of the stock. You see that nail line going through the center of the stock.

When you look at a traditional shoe display, you see a ton of weighted shoes, side weights, toe weights and heel weights. You see thinned sections. You see people who were manipulating the foot with length, width and weight.

Ideally, you’re going to get that naturally, along with a nice movement, animation — whatever the discipline is looking for naturally, but we do enhance it. Sometimes we enhance it minimally and sometimes we enhance it more aggressively.

The key concepts are soundness, flotation and penetration, enhancement, alteration, manipulation, as well as rules and guidelines for the disciplines.

5 Ethics, Support Teams and Financial Constraints

The final consideration consists of two factors that are outside of your control, yet checked by a third that is solely within your purview.

Ethics. You will be presented with influences, both intentional and unintentional, that will test you. How much are you going to do to manipulate this horse and limb, and how far are you willing to go? What do you think is right and wrong? It’s important to maintain strong ethical standards not only for the welfare of the horse, but also the integrity of farriery.

Support teams. When I started shoeing, we didn’t have equine veterinarians. We had large animal vets. We didn’t have specialists, now we do. Not only do we have veterinarians who specialize in equine concerns, but we have chiropractors, acupuncturists and bodyworkers. There are a lot of people involved. How much you can work with those other people can really help you and enhance what you’re doing or it can prove to be a detriment.

Financial constraints. When I first started shoeing 3-day event horses, it was not unusual to change the shoes out at an event two times, sometimes three. I even had one woman who I would always change them four times during a 3-day event.

The horse would come in with egg bars for the jog. She was convinced that he couldn’t pass a job without egg bars. We’d move to a basic set of shoes for the dressage. The next day, we’d go to concave. Then we’d go back to that basic set, drilled and tapped, for the stadium jumping. Before we changed back to the plain shoes for the stadium jumping, we’d have to go with those egg bars again for the third-day jog. I felt like I was shooting that foot with a shotgun with all the nail holes. The hardest part about it was trying to recycle and go green on your nail holes.

That’s a financial constraint that people gave up on. When we finally wised up and started raising our shoeing prices, it became prohibitive to change out the shoes that often. Similarly, you see the same thing with flat track runners. They initially trained in steel training plates and went to aluminum shoes on race day. That doesn’t happen anymore. Financial constraints limit clients.

While you might shoe hunters, jumpers, dressage or eventing horses, there are plenty of other disciplines that demand as much, if not more, of its athletes. Keeping these considerations in mind will inform you on how to help these horses continue competing.

LEARN MORE

Reading “Don’t Limit Your Hoof-Care Options,” in which Danvers Child discusses using as many tools at his disposal to benefit the horse.

Reading “Trimming and Shoeing Strategies for High-Low Feet,” in which Child details how he improves performance in horses with mismatched feet.

Listening to “An Interview with Danvers Child,” in which the Hall of Fame farriers talks about his history in farriery and how he approaches high-low hooves.

Post a comment

Report Abusive Comment