Understanding the importance of equine behavior and how it’s related to working with horses on a professional level sometimes can be overlooked. However, equine professionals must learn or remember how a horse’s brain is wired.

“More people are coming into our industry providing hoof care who didn’t grow up with horses or maybe had a limited amount of horsemanship skills,” says Todd Santoro, CF, APF-I, during the International Association of Professional Farriers’ (IAPF) Hoof-Care Product Knowledge Clinic at the 2024 International Hoof-Care Summit in Cincinnati, Ohio. “Second careers, or people who are looking for a trade and at the schools, are becoming aware that we have to teach them horsemanship.”

Understanding Instincts

In a horse’s mind, movement equals safety.

“Horses are prey animals with a hardwired fight or flight instinct,” says Jeremy Lucas, CF, JICF, APF-I, a member of the IAPF Board of Directors. “They are cursorial organisms, meaning they’re adapted specifically to run. This flight instinct has ensured the survival of their species for thousands of years.”

Takeaways

- Movement means safety for a horse, but lameness only compounds their natural flight instinct.

- Lame horses not only are dealing with physical pain but also psychological distress.

- Give young horses plenty of time to become acclimated to the noises that you are making during hoof care.

It’s important to remember moving is a horse’s instinct, especially when underneath a horse.

“If the horse doesn’t move, we can shoe it much faster and easier,” adds Santoro, who is president of the IAPF. “However, moving is what they are supposed to do innately, which is opposed to what we want as farriers. Even though this seems simplistic, movement equals safety, which is imperative to remember since we are under horses every day.”

If a horse is also lame at the time of shoeing, this only adds to their natural flight instincts.

“It’s important to understand a lame horse is not only dealing with physical pain but also psychological distress,” Lucas says. “We need to have a little bit more patience with sore horses because they’re fighting the pain and every instinct that they have to move.”

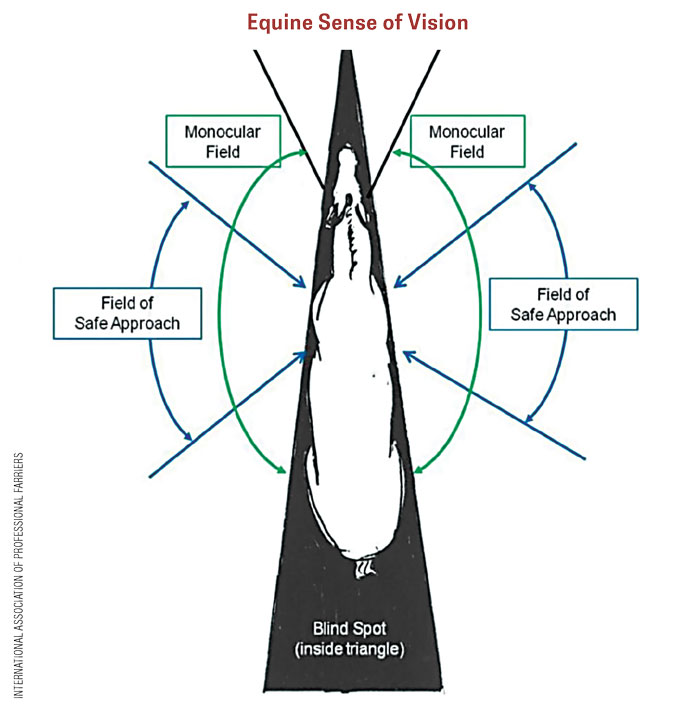

A horse’s field of vision is much different than our own, so knowing what they can and cannot see is imperative.

“What we see at 30 feet, horses see at 20 feet,” Lucas explains. “Horses have blind spots, so they cannot see 4 feet in front of their nose or at a 20-degree angle behind them. We’ve all heard, ‘Don’t walk up behind a horse.’ That’s because they can’t see you. The first thing a lot of people do when they walk up to a horse is they pet them. However, the horse can’t see them and suddenly they feel a hand touching them. Anyone who’s been around horses knows this, but oftentimes, we just get started working and forget.”

Lucas develops a routine with each of the horses that he works on to establish an understanding of what to expect.

“I generally approach the horse, touch it on the shoulder, scratch the neck, scratch them on the chest, then slide my hand down the leg to pick it up and go to work,” he says. “When I’m done, I do something similar in reverse and I walk away. Now, they’ve begun learning that’s the cue we’re done now, and they do learn this cue.”

Horses also use their acute sense of smell to become familiar with things, record information and greet.

“Be sure to give them a chance to smell you,” Santoro says. “Even though we don’t think they know who you are, they do. For example, there was this old Standardbred that I hadn’t seen in 10 years named Gypsy. They were getting ready to euthanize her and I wanted to say goodbye to her. I went out in the pasture and she smelled me for 2 straight minutes — she just kept smelling and smelling. I remember thinking that she still remembers my smell after 10 years, or that she was trying to, anyway.”

Negative Behaviors

It can be frustrating when a horse negatively acts out when trying to work on them. However, understanding why horses behave this way can help you deal with it in the future.

“The behavior is functional, meaning the behavior has the purpose of solving a survival problem in the current environment,” Lucas explains. “Horses that have successfully displayed aggressive behavior to defend themselves from predators were more likely to survive, and today, a horse kicks because its ancestors did so to stay alive. The impulses in the brain send signals to initiate the movement and the horse lifts the foot and kicks, for example.”

Kicking is not only an innate behavior but also a learned one.

“Stall kicking is a big one,” he says. “I have a couple of barns that have terrible stall kickers and the horse owners are constantly going over to the horse giving it attention. They try to stop them, but the horse is like, ‘I get so much attention from banging on these 2x10s.’”

Along with kicking, biting is a behavior that also can be learned.

IAPF Equine Behavioral Credential

Amanda Smith, CF, AF-I, CEBMS, of Acampo, Calif., is the author of the International Association of Professional Farriers Equine Behavioral Credential book that the Hoof-Care Product Knowledge Clinic lecture and this article is based on. The IAPF recognized her contributions with the IAPF Board of Directors Award at the 2024 International Hoof-Care Summit. Learn more at professionalfarriers.com.

“A horse could learn to bite from its mare or another horse,” Santoro says. “Or, like the stall kicker example, they tried it once and it worked to get attention.”

A horse’s excellent sense of hearing should also be considered.

“During a hoof-care appointment, young or inexperienced horses will be particularly reactive to unfamiliar sounds,” Lucas explains. “For example, the clicking of tools, rolling of tool carts, wire brushing the feet, etc. Be very patient with these young horses and allow them time to familiarize themselves with these new sounds.”

For hearing-impaired horses, make sure your workstation is in full view of the horse and keep your hand on their body as you move around them.

“The life we give these horses is the opposite of how they’re wired…”

“I pretty much always work with a helper,” he says. “When I need to turn on the grinder, I have the helper step out from underneath the horse before turning it on. Give the horse that couple of seconds to think, ‘Oh, it’s just a grinder — it’s no big deal.’ Remember, it’s not trying to pay attention to two things at once — that’s for an experienced horse. For a young horse, you might have to take a little bit longer when that grinder kicks on.”

Hoof-care work creates an assortment of seemingly simple sounds that are foreign to young horses.

“We make all kinds of crazy noises with our toolboxes and if we don’t have a Hoofjack, we have aluminum stands and we’re knocking those around making more noise,” Santoro adds. “A lot of horses don’t know what these noises are and then their brain isn’t going to be doing logical thinking — it’s going to move, which is what we don’t want it to do.”

An example of how sounds can affect horses is when being shod, a horse would negatively react every time the farrier hit the nail. After the farrier turned up the radio, the horse was no longer negatively reacting when hitting the nail.

Influence of Humans on Behavior

How the equine brain works vs. the human brain is important to understand. Horses lack the portion of the brain that allows for complex reasoning, which means that they can’t plot against you or misbehave intentionally. They’re simply responding to the stimuli in the present moment. Because of this, bad behavior is more likely the result of poor training or a physical or environmental issue that needs to be addressed.

“I don’t know anything about halter horses, but I trimmed some 2-year-olds that hadn’t started showing yet,” Santoro says. “I went up to the horse and started petting him on the face, neck, etc., which I always do before I pick up a leg. However, the horse trainer said, ‘What are you doing?’ I told him I was just greeting the horse. The trainer replied, ‘Do me a favor and do not touch my horses — do not greet them. Just pick up the leg, take care of the hooves and then step aside.’ The trainer explained that he has only a couple of minutes when he walks into the show arena with his halter horses and the horse needs to be statue still. The horse can’t be turning, looking, etc. He said, ‘You’re teaching that horse to be moving around if you keep greeting him.’ He was a good halter horse trainer, so I learned something that day.”

Learn More Online

Gain more insight into equine behavior and horsemanship by:

- Reading “Equine Body Language Keeps Farriers Safe and Productive,” in which Texas horseman Chris Cox details insightful techniques that improve your relationship with horses and your safety.

- Reading “Basics of Horsemanship for the Farrier,” in which horseman and farrier James Wyatt Weatherford discusses appropriate handling and communication skills that help prevent injuries to the horse, farrier and owner.

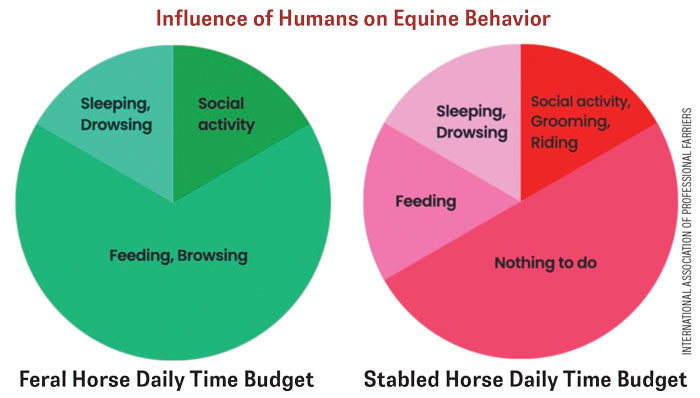

A feral horse spends most of its time feeding or browsing, and equal time on sleeping and social activity. There is no idle time for the feral horse. However, when you look at stabled horses, half of the time it has nothing to do. The other time is split feeding, sleeping, social activity, grooming, etc.

“I work at a lot of hunter/jumper and dressage barns, and those horses primarily live in stalls,” he says. “When I get them out to work on them, I’m irritated that they won’t stand still. But when I read through the IAPF Equine Behavioral Credential, I’m reminded that the life we give these horses is the opposite of how they’ve been wired for 1,000 years.”

Post a comment

Report Abusive Comment