The characteristics of a flexure limb deformity, commonly referred to as club foot, are easy to identify. Growth rings are wider at the heel, the toe is usually dished, the hoof is high on the heel and the coffin joint axis is broken forward. Radiographs often reveal that the coffin bone is deformed or remodeled. But what causes it?

After more than 50 years of experience as a practicing farrier and a doctorate in veterinary anatomy and equine nutrition, Crawford, Neb., farrier Doug Butler is well-versed in dealing with this common hoof malady. In a presentation at the late September 2017 Northeast Association of Equine Practitioners Symposium in Norfolk, Va., Butler discussed what constitutes a club foot, and went on to describe three different causes of the problem: genetics, nutrition and mechanics.

“These animals are usually born with this problem, but they can develop it as well,” says the International Horseshoeing Hall Of Fame member.

A club foot can be described as severe or not severe, with four different grades that are classified by Versaille, Ky., equine veterinarian Ric Redden, Butler says.

Grade 1. With an angle of 3 to 5 degrees higher than normal, the hoof growth rings in a Grade 1 club foot are nearly parallel, making it less serious.

Grade 2. A Grade 2 club foot has an angle of 5 to 8 degrees higher than normal, and has more heel height to the point that the heel does not touch the ground when the foot is trimmed in a normal manner.

Farrier Takeaways

- Club feet can be prevented through good breeding and proper nutrition.

- Some club foot issues can be helped by farrier work and/or surgery; others are beyond help.

- Owner education on the subject of nutrition and regular maintenance of club feet is crucial.

Grade 3. The upper one-third of the wall in a Grade 3 club foot is more vertical than a Grade 1 hoof. The growth rings are about twice those at the toe. The distal phalanx toe point can be seen as demineralized in radiographs.

Grade 4. A severe form of club foot, Grade 4 has an 80-degree angle or greater than normal. The upper 1/3 is very dished, the coronary band is level instead of at an angle and the sole is dropped. Radiographs will illustrate that the bone is demineralized, sometimes missing parts and severely rotated.

Butler essentially defines club foot as the hoof angle being at 65 degrees or more, with a contracted deep digital flexor tendon.

“We use the term ‘contracted tendon,’ but there is no such thing,” says the owner of Butler Professional Farrier Schools. “It’s contracted muscle, but the tendon is hooked to the muscle, so we say he’s got ‘contracted tendon.’”

Genetic Tendencies

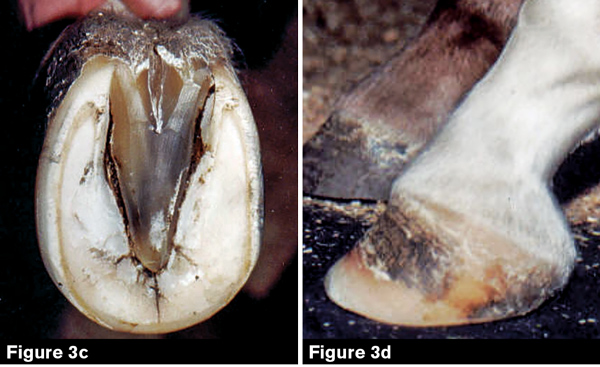

Horses can develop club feet as a result of genetics (Figure 1 see above), Butler says, and the condition might or might not be evident at birth. John Foster Lasley, PhD and author of Genetic Principles in Horse Breeding, discovered that the gene for club feet is recessive, meaning that both sire and dam must have the gene in order for it to be passed along to the foal. The chances are one in four that the foal will receive the gene.

Another genetic cause is horses that are bred to grow quickly.

“We breed for foals that will grow fast because, in America, we emphasize the young classes,” Butler says. “We’ve got racehorses going at 2 years of age or even 18 months. In Europe, they don’t run the horse until it’s 3, 4 or 5 years old.”

According to Butler, if the mare is a great milk producer, and the foal is excessively fed in addition to the milk it’s received, the young horse is at greater risk of developing a club foot.

“The foal is getting greater than 50% grain ration, which is not recommended by the National Research Council, but is done because they want the horse to grow faster,” he says. “In one case, the foal was limited-fed until weaned and then fed ad libitum (free choice). That’s the worst situation — excess grain feed to weanlings to get fast growth.”

A club foot results because when the horse is growing quickly, the bone is also growing rapidly. If the tendon hasn’t lengthened as fast as the bone grows, it pulls the toe downward, Butler says.

Club feet are more common in some breeds, notes Butler, especially in certain lines within those breeds. He also notes there has been an increase in this type of conformation in recent years.

The late equine veterinarian James R. Rooney employed pathology and necropsy to study club feet, and believed that in 1998, 15% of Thoroughbreds and Standardbreds had this condition.

PHOTO GALLERY:

NEAEP Symposium

Sept. 2017

“I think it is higher than that now,” Butler estimates. “The mild ones get by, but the severe ones will be eventually lame.”

Butler illustrates that a horse born with a club foot presents with a deformed coffin bone, and no amount of trimming or balancing can help because the horse was born with a deformed foot.

Other early causes of club feet can be uterine position and congenital deformities cause by toxins or injury during pregnancy.

“We’ve seen this a number of times when mares might have injured themselves,” Butler says. “They lie down a lot, and they have a problem in the development of the foal.”

During his presentation, Butler cited a case of genetic club feet seen in an Arabian bloodline that was popular at the time he was teaching at Cal Poly Pomona. One day, he took his class to the farm of well-known Arabian horse breeder named Frank McCoy.

“We had these Arabian horses come out,” Butler recalls. “He talked to us about how great they were and how much they’d won in the show ring. I said, ‘These horses are crippled.’”

McCoy responded that when an Arabian comes into the show ring, no one looks at the feet. They look at the topline, at the ears, and at the tail up over the back.

The horses Butler saw at McCoy’s farm were the offspring of a mare named Bint Sahara, that had 18 foals, including 11 champions. She also was the dam of Fadjur, one of the greatest Arabian show horses of all time.

“Bint Sahara had a clubfoot, and she passed it on,” Butler says.

As Butler points out, Arabians aren’t the only ones that have a genetic tendency toward club feet.

“I went to a very famous place that you would know the name of if I told you, a Thoroughbred farm,” he says. “There was a box in the tack room that had a lock on it. The farrier there opened it up and showed it to me.”

The box was filled with plastic splints that were used on the foals born at the farm because so many of them had club feet, Butler says.

Nutritional Problems

Horses that are improperly fed also can develop club feet, Butler says, noting that developmental orthopedic disease in young horses, formerly known as metabolic bone disease, can cause the condition, and is most commonly the result of excess energy in the diet. It also can be the result of myotatic reflex caused by the proprioception of pain.

Young horses fed too much grain to encourage fast growth are at risk of developing a club foot, as are horses that are simply overfed by well-meaning owners.

“We must teach our clients that excess food is not love,” Butler says. “That’s a very important concept. And it’s hard for people to buy that because they think when the horse nickers it needs some food.”

Butler provides an example of a Shetland pony he used to shoe in Pennsylvania. He went to see the pony after it foundered.

“He had big gobs of fat hanging off of his back end,” Butler says.

He then took the pony’s owners inside to talk.

“The family was there. I said, ‘This horse is getting too much to eat. You need to change what you’re doing here.’”

The family responded that they don’t feed the pony very much.

“So I said, ‘OK, let’s talk about this. What do you do every day?’ The dad says, ‘I get up real early to go to work. I go outside the door, the pony nickers, so I give him a little hay.’ The mother says, ‘Well, I get up, get ready to get the kids to school. I go out the door to empty the wash water out. The pony nickers, so I give him a little hay.’ And the oldest daughter says, ‘Well, I’m getting ready to go to school. So I go out the door after I eat breakfast. The pony nickers, so I give him a little hay.’ They’ve given this pony enough food to feed four or five horses. There was no communication.”

Mechanical Issues

The most common mechanical issue that can cause club feet in horses is grazing posture, Butler says.

“When a young foal is born, it looks like a spider, and it has a short neck,” he says.

“The horse places one foot ahead of the other. It becomes a habit that eventually affects the foot conformation due to their weight bearing change.”

This stance slows the heel growth of the forward foot, and slows the toe growth of the backward foot. As a consequence, the forward foot becomes under-run, and the backward foot becomes clubby. The muscles on the leg with the club foot become tight and contracted.

“This is more common today because we have more warmbloods,” Butler says. “It is especially common in these large horses.”

Horses also are being bred to be taller, Butler says, which is also increasing the incidence of club feet. In halter classes, the tallest horses are rewarded with wins, which encourages the breeding of horses with greater height.

A Dutch warmblood study conducted in 2009 at the Wageningen University in the Netherlands looked at the prevalence and inheritability of uneven or mismatched feet, using the 44,840 horses in the warmblood registry. The study was conducted from 1990 to 2002.

The study revealed that 5% had uneven feet, and the percentages increased over time because the winning horses were bred to each other. The study showed a correlation between tall wither height and a short neck, which causes an awkward grazing posture.

Of 576 sires, 60 had no problem. However, in six sires — 25 percent of the offspring that were produced — had uneven feet.

“Because the inheritability was quite low,” Butler says, “it had to be a lot more nurture as opposed to nature.”

The recommendation at the conclusion of the study was to trim feet regularly and avoid breeding horses with a history of club feet.

Butler provided the example of an Arabian yearling with a mild club foot caused by the horse’s grazing posture. The right front foot was narrower than the left, which means the narrower foot had a deformed bone that was not developing normally.

To trim this horse, a farrier should use a wedge underneath the toe to get the heel to touch the ground (Figure 2a). A card then should be pushed under the heel. If the card fits between the hoof and the ground, the heel is not touching. If the card won’t fit, the heel is touching, Butler says.

“If the heel will touch, then we can cut that much off the heel safely and put the foot back into balance (Figure 2b),” he says. “If we do that regularly and often enough, a lot of these horses will grow out of it.”

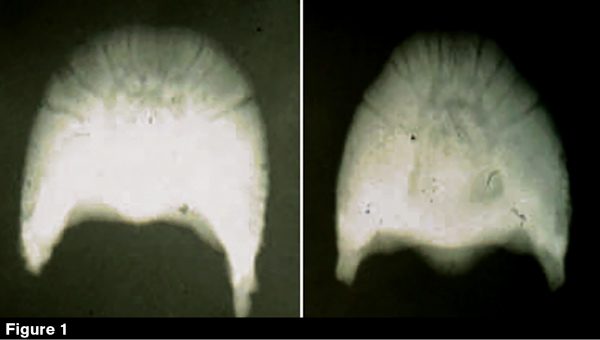

Butler illustrated managing club feet using a Morgan pleasure show horse (Figures 3a, 3b, 3c, 3d) that requires frequent maintenance.

The horse had a steep pastern, which required Butler to pull the shoe back to remove the dish from the front of the foot. This exposed the scarred horn from the mild laminitis that’s occurring in the foot. Because this was a show horse, the toe was blackened and the hole was filled in. In this situation, a veterinarian also could have performed a subcarpal check ligament desmotomy to help the muscles to stretch.

According to a paper titled, “Long term results of desmotomy of the accessory ligament of the digital flexor tendon in horses,” by P.C. Wagner, B.D. Grant, A.J. Kaneps and B.J. Watrous, published in the Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association in 1985, 80% of horses with club feet that were studied and underwent surgery achieved their intended purpose.

“Don’t forget that means 20% can’t,” Butler says. “Prognosis is better for showing and pleasure than for racing. And they have a better chance if it’s a deep flexor problem than a superficial flexor problem, mainly because of the age.”

He notes that there are higher incidences of club feet in show horses because of the tendency to over supplement diet with excess protein energy, minerals and vitamins to encourage rapid growth.

According to Butler, when reviewing the athletic potential of horses surgically treated for development orthopedic disease, about 60% of horses with angular deformities have successful careers. Horses with moderate contracted tendons might be considered an occasional success, while horses with severe contracted tendons tend to do poorly.

“So the best chance is when you have a deep flexor problem,” he says. “The worst is a superficial flexor problem.”

In summary, Butler emphasizes that many show horses have a club foot and can have successful careers, but they must be maintained. He also stresses discussing the importance of proper nutrition with clients.

“We talk about that first,” he says. “Then we talk about what are we going to do to help the horse. But if they don’t do the nutrition thing, you might as well just pack up and go home and forget it, because you’re not going to help the horse.”

Post a comment

Report Abusive Comment