What is the ideal length that hoof wall should be trimmed to?”

Gerard Laverty’s question was met with a pregnant pause before the attendees at the Oregon Farriers Association mid-September clinic chuckled all at once.

The answer is rather elusive. Most farriers know it when they see it, but assigning a single number to it is simply irresponsible.

“When you read any book, it will not give you hard and fast directions on how much to trim off a horse’s hoof,” says the faculty farrier at Kwantlen Polytechnic University in Surrey, British Columbia. “I use a toe rule on every horse I trim for that reason.”

Like many of his colleagues, Laverty used dividers in his trimming regimen. That changed when he was introduced to the toe rule.

“I had a number with the toe rule, instead of just a space,” he says. “When using dividers, you trim one toe and you’d go to the other one and scribe it to get them the same length. But what length is it? Unless you actually measure it, you didn’t have a number. With the toe rule, you get a number.”

Farrier Takeaways

- Accurate measurements from a toe rule provide a number for the ideal hoof wall length.

- Horses’ hind toes generally are slightly longer to provide leverage.

- Starting new farriers on the hind feet first, rather than the front, can help avoid trimming the fronts too short.

- Ideally, the measurements taken of the foot will be fairly uniform.

The Day-To-Day Goal

Although the number that the toe rule provides is Laverty’s stated reason, his rationale actually runs much deeper.

“Our day-to-day goal with the horse is to have ideal circulation through the corium, which produces the hoof,” he says. “The amount of hoof wall you’re taking off is telling you how the blood is circulating through that foot.”

To emphasize his point, Laverty circled back to an earlier question regarding the use of wedge pads on horses.

“Can we get them out of those wedges?” he says, repeating the question. “Take the horse out of the wedges and see how the hoof wall develops. When you return to the horse and all you’re trimming off is toe and nothing at all off the heel, then there’s been very little circulation in the back part of the foot. You still have a problem. If you’re able to remove as much heel as you did toe, the horse is as close to ideal circulation as possible because it has even hoof wall growth from the heel through the quarters and the toe since it’s generated from the coronary corium.”

Frog And Sole

There’s some ambiguity when attention turns to the frog, as well.

“We tend to have a habit, as a group, of over trimming the frog,” Laverty says. “There has to be some variability in that, depending on where the horse lives. Horses will retain more frog in a drier climate than they will in a wetter climate.”

Yet, the equine foot generally sheds the sole and frog. So why is it trimmed?

“We shouldn’t,” he replies. “We should just be trimming the fingernail, which is the hoof wall. But, horses are kept in situations where they retain sole, so we need to remove sole so we can shorten the wall. Well, how much sole should we remove? Only enough to get the fingernail — or hoof wall — to the ideal length. What’s the ideal length?”

An Educational Experience

Shortly after ditching the dividers for the toe rule, Laverty made another change.

“Pretty quickly I found that I could never get the hind hoof walls as short as those on the front,” he says. “My hind toes were always slightly longer.”

Laverty concluded that the hinds are meant to be a little longer.

PHOTO GALLERY:

Oregon Farriers Association Clinic – Sept. 2017

“The horse is a rear-wheel drive machine,” he says. “It has a lot more pushing power in the hind end than it does in the front end. So it can manage a longer lever — not much longer; 1/8 of an inch is about it. I switched and started shoeing the hind end first.”

That change in habit proved to be profound when he started teaching farriery.

“If you get students working on the hind end first and they make a mistake by taking a horse too short, it’s not going to be a disaster for the horse,” Laverty explains. “If they make a mistake on the front end, it’s a bigger mess.”

It’s now a rule of thumb for his students.

“If you trim the hind end to the correct length and measure it accurately, now you can go to the front end and I can absolutely guarantee you can trim the front end to this number,” he says. “If you have someone just starting out and have them follow this routine, they can be much more confident that they won’t get themselves in trouble on the front end. But, it’s all contingent on them being able to properly use the toe rule. If they can’t use it, then all bets are off.”

Three Planes

Laverty looks at a healthy frog as a wedge of three planes.

“Obviously it’s a wedge from the front to back,” he says. “It should also be a wedge from top to bottom. It’s also a wedge from the back of the foot, diving down into the foot.”

As alluded to earlier, trimming the frog can be a trouble spot. Some farriers often describe trimming back to the widest point of the frog. Laverty believes that in most cases the hoof wall’s last point of bearing should be taken to the high point of the frog.

“The widest part of the frog is in the heel buttress, which is too far back for me as far as trimming to,” he says. “Shoeing to it is OK. Having the end of the shoe come back to there, but taking the heel down until it gets there is taking too much heel off the horse in my book.”

While teaching how to trim a hoof, Laverty realized there’s a correlation between what one thinks is the ideal toe length and the distance from the tip of the trimmed frog to the last point of the bearing surface of the trimmed hoof on a well-conformed horse.

Using The Toe Rule

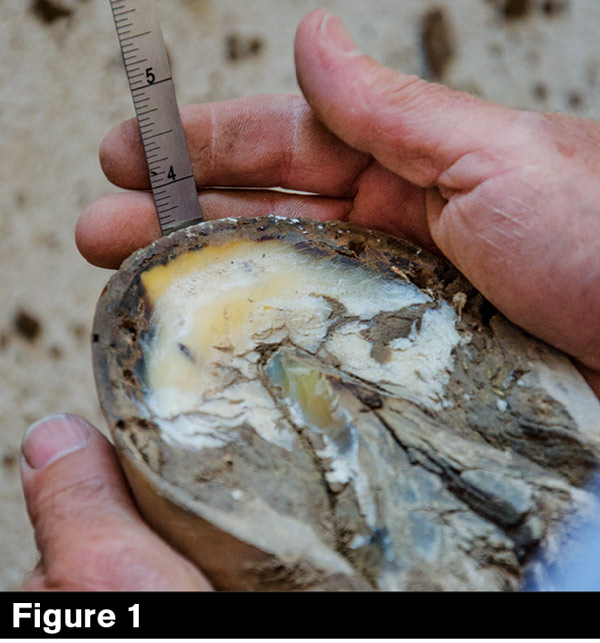

After trimming the front half of the foot to what you think would be the ideal toe length, measure it carefully (Figure 1).

Trim the frog so you can see where the apex attaches to the sole and there’s no movement from that tip to the last point of the heel. Measure from the attached tip of the frog where it touches to the sole to the last point of the bearing surface (Figure 2). The other heel should be the same.

Laverty gets a reading of a little more than 3½ inches in each case on this horse.

“Ideally, that will be the same dimension on the average healthy hoof,” he says, noting that you will not get the same measurement with collapsed heels or a club foot. “There will be horses that if you trim to that, you’re just going to get yourself in trouble.”

The demonstration brought Hank McEwan, an International Horseshoeing Hall Of Famer from Merritt, British Columbia, to Laverty’s mind.

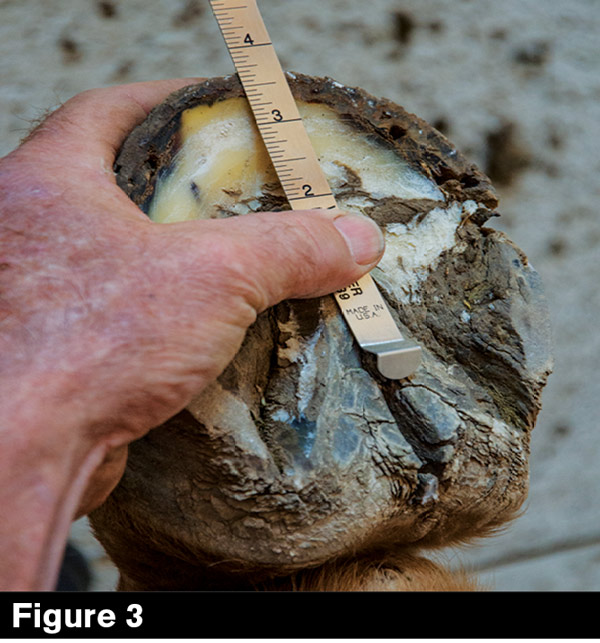

“Old Hank McEwan taught me that it should never be more than 2 inches from the tip of the trimmed frog to the front of the horse’s foot (Figure 3),” he says. “If it’s more than 2 inches, it’s going to have to be a monster horse.”

Mistakes Happen

Although Laverty has enjoyed success with this method, mistakes happen. While shoeing a warmblood with big, narrow hooves, he was instructed to make sure the feet were as short as possible.

“I got myself in a world of trouble by taking that horse short,” he recalls. “What it taught me was horses with narrow, boxy feet are like people who like to have their fingernails long. If you take them short, they’re going to really suffer. Whereas horses that are real flat-footed are more like people who pick at their fingernails so much that they are halfway up their finger, and they seem to be fine.”

Using the toe rule, he could barely get them less than 4 inches. However, when he went slightly shorter, problems arose.

“I didn’t have blood on the floor, but the horse was not happy,” Laverty says. “None of us are infallible. We’re still just practicing. I certainly don’t get it right all the time. I’m going on past experience to help me make good judgment on the next one.”

Post a comment

Report Abusive Comment