The motion of a horse is a complex process, with lots of structures involved to propel the horse forward. Horses are built for speed and their bodies reflect that design.

We know farriers can have an effect on the horse’s soundness. But how does a horse’s movement change what you should be doing for its feet? Jenny Hagen, a professor and researcher at the Institute of Veterinary Anatomy of Leipzig University in Germany, shared this information in a lecture at the 2017 International Hoof-Care Summit in Cincinnati, Ohio.

Movement And The Farrier’s Effect

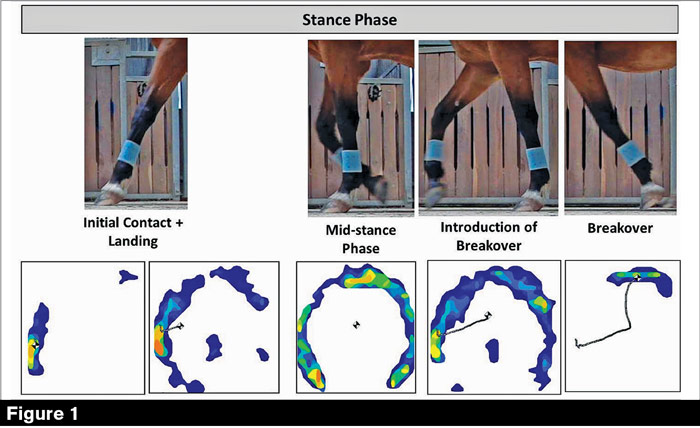

Hagen says the horse’s movement is divided into two parts: the swing phase and the stance phase. The swing phase is the period of time when the legs are off the ground. The stance phase is the period of time when the horse’s hoof is on the ground.

“It’s very difficult to have a specific effect on the horse’s movement with trimming,” Hagen says. “But everything we try to affect here is connected to your work on the foot — it’s an indirect influence on the proximal/upper locomotor system you can have to try to improve problems there.”

Farrier Takeaways

- If a horse has a less-than-ideal contact and landing pattern, make sure it’s actually a problem that needs to be addressed — it could just be a unique foot pattern belonging to the horse.

- Trimming solely to achieve a straight alignment does not change the horse’s gait pattern or stance pattern. It is necessary to evaluate the horse in motion and trim for the desired specific changes.

- The hoof capsule, dermis and bones are all affected by pressure on the hoof. Applying shoes that cause pressure peaks or unequal loading can have detrimental effects throughout the horse’s hoof.

One example of an effect a farrier can have is when the results of hoof trimming or shoeing improve the balance of the muscles, the horse’s back muscles can relax, which relieves pain in all of the horse’s muscles.

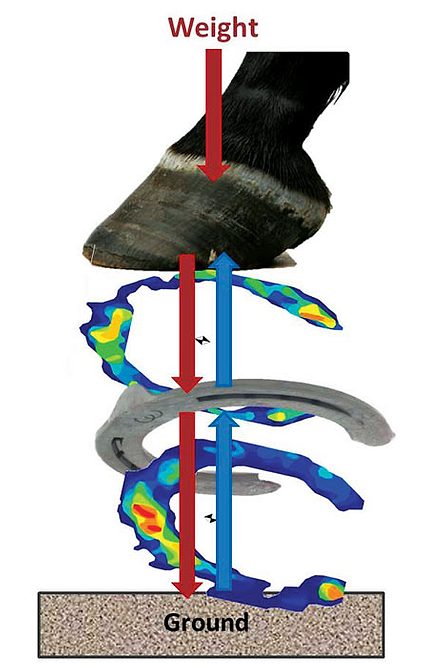

In the stance phase (Figure 1), the horse has the maximum vertical load on the hooves, which means the highest forces are directly affecting the horse’s hoof and distal limb, in particular the suspensory apparatus of the fetlock joint, including the tendons and ligaments. Hagen says this is also the phase in which you can have a direct effect on the angulation of the interphalangeal joints and the load affecting associated tendons or ligaments with shoeing and trimming.

In the swing phase, adjusting the toe length means an effect on the arc of the stride — the way the limb is lifted and placed down again.

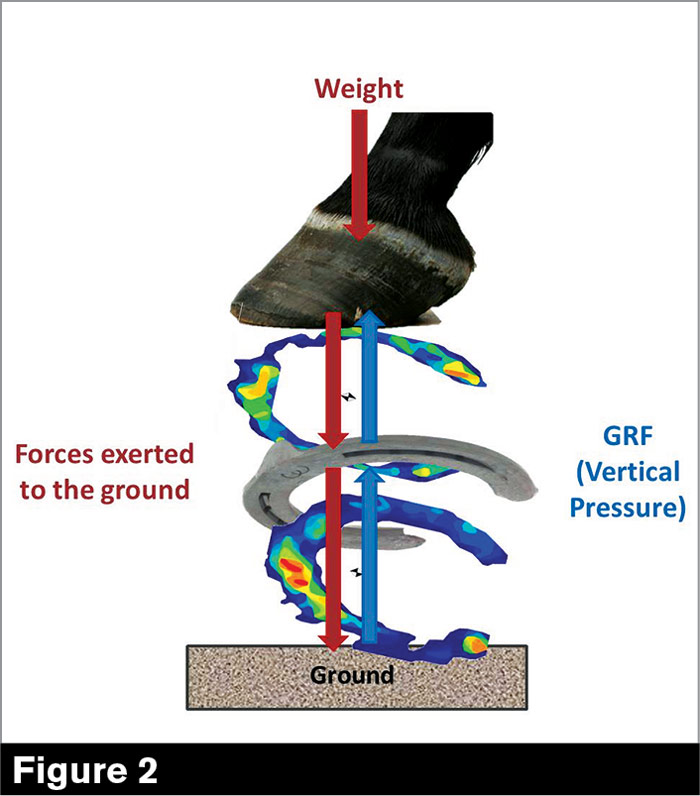

All horses, regardless of use or discipline, have high forces affecting the distal limb during the stance phase (Figure 2) — whether it’s the initial contact with the ground, the landing phase or the mid-stance.

“The horse’s weight caused forces to go to the ground, and the same amount, those forces are going back to the hoof,” Hagen says. “These forces affect the limb during contact with the ground. And of course, the higher speed the horse is moving, the higher the forces are affecting the hoof and the distal limb.”

Gathering Information

Hagen says most farriers evaluate the movement of the horse by letting the horse walk to and away from you so you can judge the symmetry of the pelvic movement or the head movement, and the way the horse moves the limbs.

“It’s a very subjective thing — you can have three veterinarians or five farriers, and everybody has a different viewpoint,” Hagen says.

Some research groups and veterinarians have used a sensor-based system to obtain more objective data. Hagen used an affordable system called Tekscan for measuring the horse’s movement, using a sensor secured to the underside of the hoof. It is wirelessly connected to a data logger, with provides a live video that can be saved. The 1-millimeter-thick sensor can be attached under different conditions at the hoof for measurements with or without rider, with different types of shoes or at different surfaces.

For this study, Hagen used the sensors to measure the force between the horseshoe and the ground simultaneously with the forces applied to the hoof capsule itself. For one study, she measured the movement of 25 horses, on four different surfaces, but focused on the difference between force on concrete and on deep sand. In another study the hoof-ground contact in walk was examined and long-term monitored with regard to different trimming protocols in 75 sound horses. The horses’ strides were measured over 7-10 strides. All of the horses were checked before measurement and radiographed — all were warmblood horses without hoof problems or limb deformities. And all were sound.

Findings From The Study

After reviewing the data from her study, Hagen says the point where the highest forces affect the hoof for the first time in the stance phase is the initial contact point — it’s a quick increase in forces and all of the ligaments and tendons have to stabilize it.

“That’s actually a quite stressful part of the stance phase,” Hagen says.

The most optimal landing pattern is called the plane landing, where all parts of the hoof achieve ground contact at the same time, she says. A lateral landing, where the horse lands on the lateral side of the hoof first, is also common. Hagen found about 1/3 of all the horses measured had a plane landing, another 1/3 had a lateral landing.

A medial landing — when the horse lands on the medial side of the hoof first — is undesirable, and seems to be correlated strongly to the limb and body conformation. Hagen says the horses in the study with a medial landing tended to have a limb that was a bit varus, or toed-in.

Hagen says they found a surprising amount of horses had a toe landing, which can be associated with problems in the palmar region of the hoof.

“But sometimes you can’t find any problems and they aren’t painful,” Hagen says of the toe landing. “If you can’t find anything — you have a sound horse without any problems or sensitivity in the palmar region, or positive provocation tests — then I would say this toe landing belongs to the horse as an individual motion pattern. It can be a normal physiological footing.”

Hagen also recorded horses with a heel landing, where the horse’s heel strikes the ground first. It was more noticeable at faster gaits. This landing pattern is aimed for in some specific trimming concepts and connected to a sound hoof. However, since just two of the 75 horses showed this type of landing, this aim is questionable. The individual preference of each horse should be respected.

“If you have a customer who is really worried about the initial contact and landing pattern of his horse, I would really carefully judge if there’s really a problem or if it’s just a motion pattern belonging to the horse’s body,” Hagen says.

Making Changes

When a horse has a problem in its structure, Hagen says it’s important to differentiate which phase of the stance the issue is occurring. Is it the shock and vibration affecting the short ligaments or joints in the toe during initial contact? Is it the maximum load and stance operators in the mid-stance? Or is it the deep flexor tendon during the early phase of the breakover? All of these require a different focus while shoeing.

You also need to consider the horse’s living situation — is it more static, currently on stall rest? Back to work a bit with a more dynamic influence? Hagen says you need to focus on which structures are affected with a problem, and which ones would you like to relieve, and at which phase can you best relieve them.

Stabilization, impact peak, initial contact, maximal load and the different structures affected all can be impacted by good farrier work. However, Hagen cautions against trying to do too much at one time.

“If you are trimming or shoeing and you try to change one of these parameters, I can promise you it’s very hard and often not possible to optimize the landing and the load during mid-stance at once,” she says.

The Wedge Affect

Hagen examined the horses with a unilateral landing on one side. In these horses, they affixed side wedges on the opposite side to see how it affected the landing.

“Few horses responded in the intended way by immediately changing their landing toward a plane contact during initial contact,” she says. “However, the same amount of horses were able to compensate the effect of the wedges and keep their individual landing pattern. In addition, in the horses that we ‘optimized’ the landing toward a plane contact, simultaneously, the load shifted dramatically to the wedged side during the maximum load during mid-stance. Therefore, it is important to judge if it is really worth it to change the initial contact or if it is better to optimize load distribution during mid-stance. Both together is not always possible.”

The Trim’s Influence

Hagen had another study of 75 horses, following them over 10 months, measuring them with sensors before and after they were trimmed. One of the things Hagen’s team noticed was that trimming solely to achieve a straight alignment did not change the horse’s gait pattern or stance pattern — it was necessary to evaluate the horse in motion to make appropriate changes.

“If you would like to change the initial contact, the gait pattern or the stance phase of the horse, you need to aim specifically for it. You can’t just trim static or geometric,” Hagen says. “But sometimes, you should just leave it to the horse, if it will be too hard of a change for the maximal load in the mid-stance. Sometimes you should think long-term — don’t try to make a change all at once.”

One example was a horse with an asymmetrical hoof and a significant lateral landing. The farrier first tried to trim the hoof to make it more symmetrical, but the motion of the horse didn’t change. It still landed on the lateral hoof wall.

“Although he tried his best, it’s not going to change the lateral landing,” Hagen says. “If you were to trim further, to work to force the initial contact toward a plane landing, you would shift the rate completely to the other side during maximum weight bearing in mid-stance. But in this case, he almost managed to improve the horse. It has a slightly less lateral landing, but the horse looks nicer and more relaxed — he improved the load at the mid-stance. I wouldn’t have gone further to improve the horse — maybe over time, it can be improved. Just avoid overtrimming or overcorrection.”

Another thing to note — Hagen says the higher up the horse’s legs the deformational problem lies and the longer it exists, the less impact you can have with trimming and shoeing.

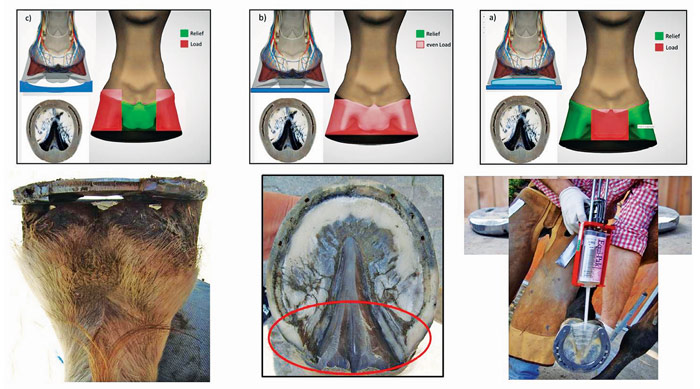

There are various ways of applying bar shoes for different orthopedic purposes — loading the hoof capsule (left), even load (center) and loading the frog (right). Photo: Jenny Hagen and Effigos Ag

Bar Shoes

Hagen says caution should be exercised when applying a bar shoe for weak heels, underrunning heels or long and unstable heels. In the examinations, with regard to the effect of modified horseshoes on the biomechanics of the distal limb, the bar shoes created pressure peaks at the heels.

“This is probably related to the reduced flexibility of the hoof capsule in the palmar region and to the steeper alignment of the hoof in penetrable ground,” Hagen says. “The reduced sink in the palmar region causes pressure peaks at the heels.”

The positive thing about bar shoes is they can be adapted in the way the load is distributed between heels and frog. It can be made to be neutral, allowing you to load the frog and heels equally — helpful for a laminitic horse where you want to support the palmar region and relieve the diseased region at the front of the hoof. You also can use a bar shoe to relieve pressure on the frog, such as when you are working with a horse with navicular. And you can use various cushions and bar lengths to achieve less strain at the heels to recover them from cracks or stress.

If a veterinarian asks you to apply bar shoes, make sure you discuss how you’ll use them to achieve your goals.

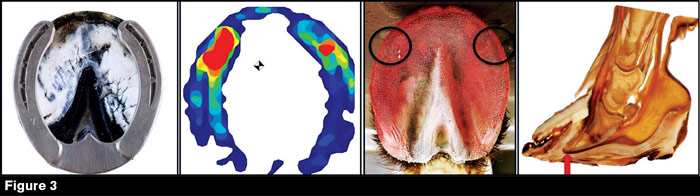

Open toe shoes lead to high-pressure peaks (Figure 3) under the end of the branches, according to the data Hagen gathered with sensors. These shoes are used to relieve the anterior/dorsal part of the hoof and to improve breakover. However, the effect of this shoe is strongly connected to their manufacturing and adjustment to the hoof. They’re particularly hard on horses with a thin sole or previous bouts of laminitis. But handcrafting by grinding the edges and perhaps packing the shoe can help you achieve your desired results with no discomfort from the horse.

Forces And Breakover

Hagen says there are several definitions of breakover.

- The length of the toe, defining the distance the horse has to breakover.

- The distance between the tip of the distal phalanx and the last contact of the hoof with the ground.

- The last point where the horse is breaking over.

- The time period from lifting the heel to the last contact.

A lot of research has been done trying to find a difference between setback breakover and breakover with a normal shoeing. Hagen says that the strains and the tendons can be reduced by a setback breakover, as well as the pressure peaks affecting the toe. It is not proven that the time of breakover changes by the application of different shoeing types.

The forces affecting the breakover also can be reduced by using a rolled toe or a rocker shoe.

Conclusions

Hagen says pressure distribution on the hoof is affected by shoeing — not just the hoof capsule, it also affects the dermis and the bones. Applying shoes that cause pressure peaks or unequal loading can have detrimental effects on the horse’s hoof throughout.

“Don’t change parameters just because you think it would look nice,” Hagen says. “Try to think functional. Try to make the compromise between landing, mid-stance phase, and load. And don’t forget — the bone in a hoof capsule can change related to biomechanical forces — it’s a very active tissue.”

Post a comment

Report Abusive Comment