Managing a horse with mismatched feet can be a challenge for both the veterinarian and farrier. At last winter’s American Association of Equine Practitioners’ convention, a session undertook both the veterinarian and farrier’s role in these cases.

By reviewing what mismatched feet mean and addressing the issue based on principles of farriery, the goal was to help attendees improve their results in management of these cases.

Veterinary Evaluation Of Mismatched Feet

It is important to begin any discussion of mismatched feet by defining it first. This task and the overall discussion of the veterinarian’s role in diagnosing this was handled by equine veterinarian Stephen O’Grady of Keswick, Va.

“This could be defined as forefeet conformation that has a high or upright hoof angle on one foot and a low hoof capsule angle on the contralateral foot,” explains the Hall Of Fame veterinarian.

Mismatched feet can affect both soundness and movement.

“You can see this with a dressage horse,” he says. “The horse may look fine to you, but the rider may come back and say, ‘This horse isn’t moving right.’ You better pay attention to the experienced rider.”

Appropriate farriery is effective, but may not be inherently obvious. “Sometimes we are creatures of habit,” explains the farrier-veterinarian. “We do things a certain way and horses tend to be done the same way. This type of foot conformation needs to be approached on an individual basis.”

Farrier Takeaways

Before taking action, the footcare practitioner must understand the horse’s conformation and mechanical forces involved with each foot.

Address each foot individually rather than trying to match the feet.

Trimming and shoeing should be based on farriery principles to improve the structures and function of the individual foot.

There are several reasons why mismatched feet hold relevance for veterinary clinical practice:

- Mismatched feet may contribute to poor performance, subtle lameness and a shortened anterior phase of the stride on the foot with the upright conformation.

- “A lot of times, it could be the low-heeled foot or the high-heeled foot — the horse just isn’t right,” explains O’Grady.

- The upright foot may exhibit toe first landing, which may lead to sole bruising, toe cracks and other issues.

- Shortened anterior stride on the upright foot often leads to overloading on the foot with the lower angle. “When you think about it, the upright foot is going to break over quicker and have a shorted stride, therefore it is going to spend less time on the ground,” explains O’Grady. “So the low angle foot or the contralateral foot is going to be on the ground longer. It will take more stress on the heel.”

O’Grady reminded his veterinarian colleagues in attendance that as practitioners they will examine horses comprehensively, which includes properly looking at the complete foot.

“We need to get down on the ground and really look at those heels,” he says. “And when we look at those heels in this manner, we’re seeing their true length.”

O’Grady then reviewed the common visual identifiers with mismatched feet.

“The first place you start is the disparity of hoof angles — one with a low angle and one with a high angle,” he says.

“After that, you look at disparity of size. You may have the same ground surface, but when you look at the horse from the front, the upright foot will be a little narrower.”

O’Grady then looked at the disparity in the hoof wall growth between the toe and the heel of each foot. Another indicator could be markedly different angles of the horn tubules in the foot with the high heel vs. the low heel.

Presenting an image of a horse with a straight hoof pastern axis (HPA), O’Grady noted the disparity in the heels. “Furthermore, the disparity in the upright foot could range from a high hoof angle with a straight hoof pastern axis to a club foot with a flexural deformity. We’re going to address each of those in a slightly different way,” he says.

It is crucial to evaluate the foot conformation. When analyzing the upright foot, it is important to note the HPA axis, the height of the heel, the dorsal hoof wall, sole depth and the position of the frog.

“The sole is important, you want to note its flatness or concavity,” he says. “What’s really important to me is the frog. Is it recessed on one side or recessed on the other? Either way, I want to deal with it.”

With a recessed frog, O’Grady notes the impaired foot function in the palmar section of the foot.

Timing can be improved by good farriery …

“I want to have the back part of the foot load sharing,” he says. “I want to have the hoof wall and the frog on the same plane. When we don’t have the frog on the same plane as the heels, the entire load is placed on the hoof wall.”

When evaluating the low heel foot, again the HPA also is important to note. O’Grady says practitioners should also look at the length of toe, the heel structures, the sole and the frog, noting that with the low heeled foot, the frog is generally prolapsed.

Typically the low-heel foot is generally overloaded because it is taking more weight and spending more time on the ground. The equine veterinarian says that an important consideration to remember is that the shortened anterior stride of the upright foot will equal more time on the ground for the low-heel foot.

Despite the technological advances in imaging, O’Grady holds that the hoof tester remains one of the most important tools. Both farrier and vet should carry these, but it’s important to know how to use this tool properly.

“Don’t just go to one foot and simply go to the heels or the toes or the quarters,” he says. “Get yourself a systematic approach in which you check the entire foot.”

With the testers, it is important to recognize the horse’s discomfort, but you can also use the hoof testers to evaluate the integrity of the foot structure.

When watching a horse in motion, O’Grady wants to see it under tack and rider. During this evaluation, he wants to look for lameness and note the stride length and strike pattern (how the foot lands on the ground).

“Observing the strike pattern, you’ll find the toe-first landing on one or both feet,” he says. “In order to look at the strike pattern, you need the horse on some kind of harder surface.”

Radiographs prove to be a valuable tool in the evaluation of both feet. With the upright foot, the HPA, length and concavity of the dorsal hoof wall sole thickness and depth, and the amount of removable heel can be assessed.

With the low-heel foot, the practitioner wants to note the HPA, length of the dorsal hoof wall, sole depth, soft tissue structures in the palmar area of the foot and the angle of the distal phalanx’s solar border.

Improvement Through Farriery

After discussing the evaluation, O’Grady then touched on the farrier’s role in the management of mismatched feet.

“Treatment should be based on farriery principles to improve the structures and function of each individual foot,” he says. “This is so important with mismatched feet — don’t try to make one look like the other.”

The principles to address on both the upright and low-heel feet are:

- Improve the HPA.

- Decrease the moment on the distal interphalangeal joints (breakover).

- Improve the function of the heel structures.

- Decrease stresses on the deep digital flexor tendon (DDFT) as necessary.

Next, Bob Pethick provided more insight on what the farrier can do to help a sport horse with mismatched feet. The Bedminster, N.J., farrier noted how timing between the limbs is affected and often appears as a shorter stride with mismatched feet.

“In my mind, it is a timing issue in what I’ve seen in the slow-motion videos that I’ve taken of these horses,” he holds. “It is more of a timing issue with how long the foot is on the ground.

“Timing can be improved by good farriery, as well as function of the hoof capsule, movement and soundness.”

After obtaining and examining necessary radiographs, Pethick says to trim the low-heel foot first.

“Trim to restore solid horn in the back of the foot by removing run forward collapsed heels and to maintain sole depth in the front half of the foot, being careful not to over pare the sole,” he advises.

Pethick notes that it is a common practice to shorten the toe excessively to raise the angle. As it is important to maintain significant sole depth for the horse’s benefit. It would be better to address shortening the toe by dressing the dorsal wall back, rather than shortening it from the ground surface.

“Collapsed heels and folded bars need to be addressed by trimming to restore and straighten the bearing surface as much as possible,” he adds. “The frog will be a major weight-bearing structure in this type of hoof and should be trimmed lightly, not over pared. The main goal in mind is to trim this hoof to function the best it possibly can.”

Pethick then addressed the upright foot. Along with radiograph information, wedge tests can provide guidance. This helps determine how much heel can be safely removed without making the horse uncomfortable.

“This horse remained comfortable with one, so we then placed two wedge pads under the foot (Figure 1),” he says. “The horse didn’t try to step off, the heel didn’t float — there is plenty of length.

“The worst thing you can do is over-lower the heel,” he notes. “I think that any farrier who has ever over-lowered the heels tend to leave too much heel height on these feet to try to avoid their past experience. Excess heel height will limit the expansion of the hoof capsule, stress the coffin joint, as well as other structures and result in a stilted gait with a hard heel first landing.”

The trim must improve the HPA, but without stressing the DDFT and the accessory ligament (AL) of the DDFT. The farrier also should take care to retain sufficient sole depth under P3.

“If the toe of this foot is shortened excessively, it is not possible to trim the heel, as you will be dangerously close to sensitive sole in the middle of the foot,” he says. “Always trim this foot from the heels forward to maintain the sole depth under P3.”

Safely restoring the HPA and reducing excessive growth without compromising the DDFT and the AL-DDFT will return function to the hoof capsule.

“The hoof capsule will widen and the frog will become more robust,” the Hall Of Fame horseshoer says. “Trimming will restore the ratios around the center of rotation. Further management can be accomplished by adding mechanics into the shoe to facilitate turnover, which eases the stress on the hoof capsule and limb.”

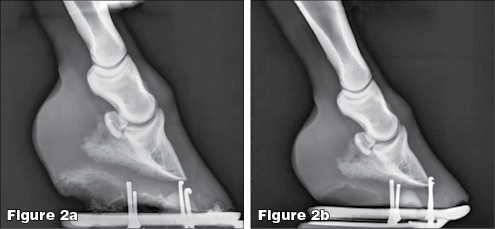

Once the feet are properly trimmed, the shoe selection should be guided by what best suits the horse’s performance needs. With the case above, Pethick opted to reset the aluminum shoe. Figures 2a and 2b show the radiographs of the pre- and post-shoeing, respectively.

“This horse is a show hunter, so we don’t want to add any excess weight,” he notes. “If it was a dressage horse, we might approach the feet differently. I would probably do something as far as supporting the frog and adding more weight in the form of support material underneath a pad.”

Pads may be used based on the amount of growth that was available to work with and if the trim adequately restored the HPA and retained sole depth.

“I prefer to use frog support pads and support material, such as Equi-pak or Advanced Cushion Support to spread weight bearing over a larger area to promote function and counter the effect of peripheral loading,” he explains.

Pethick wants shoe placement on both feet to be 50/50 from the center of rotation, with the toe rockered slightly from the back of the web or rolled to ease turnover.

Pethick showed both the pre- and post-shoeing of the horse trotting using OnTrack video gait analysis software. Issues related to the mismatched feet had markedly improved by his efforts.

“By understanding good trimming techniques, shoe placement and shoeing the hoof to bear weight as evenly as possible, horses can move the best they can for their conformation and remain sound longer,” he concludes.

Post a comment

Report Abusive Comment