The prevalence of asymmetrical, mismatched or high-low feet has changed dramatically over the past half-century. What once was rare is now an almost daily occurrence that farriers must maintain to keep horses performing as well as possible.

Yet, how should farriers tackle asymmetry? Maintenance techniques have evolved almost as dramatically as high-low feet have become commonplace. During his presentation at the 48th annual American Farrier’s Association Convention in Tulsa, Okla., Danvers Child discussed characteristics of high-low feet, how they affect performance and how he approaches trimming and shoeing them.

What are High-Low Feet?

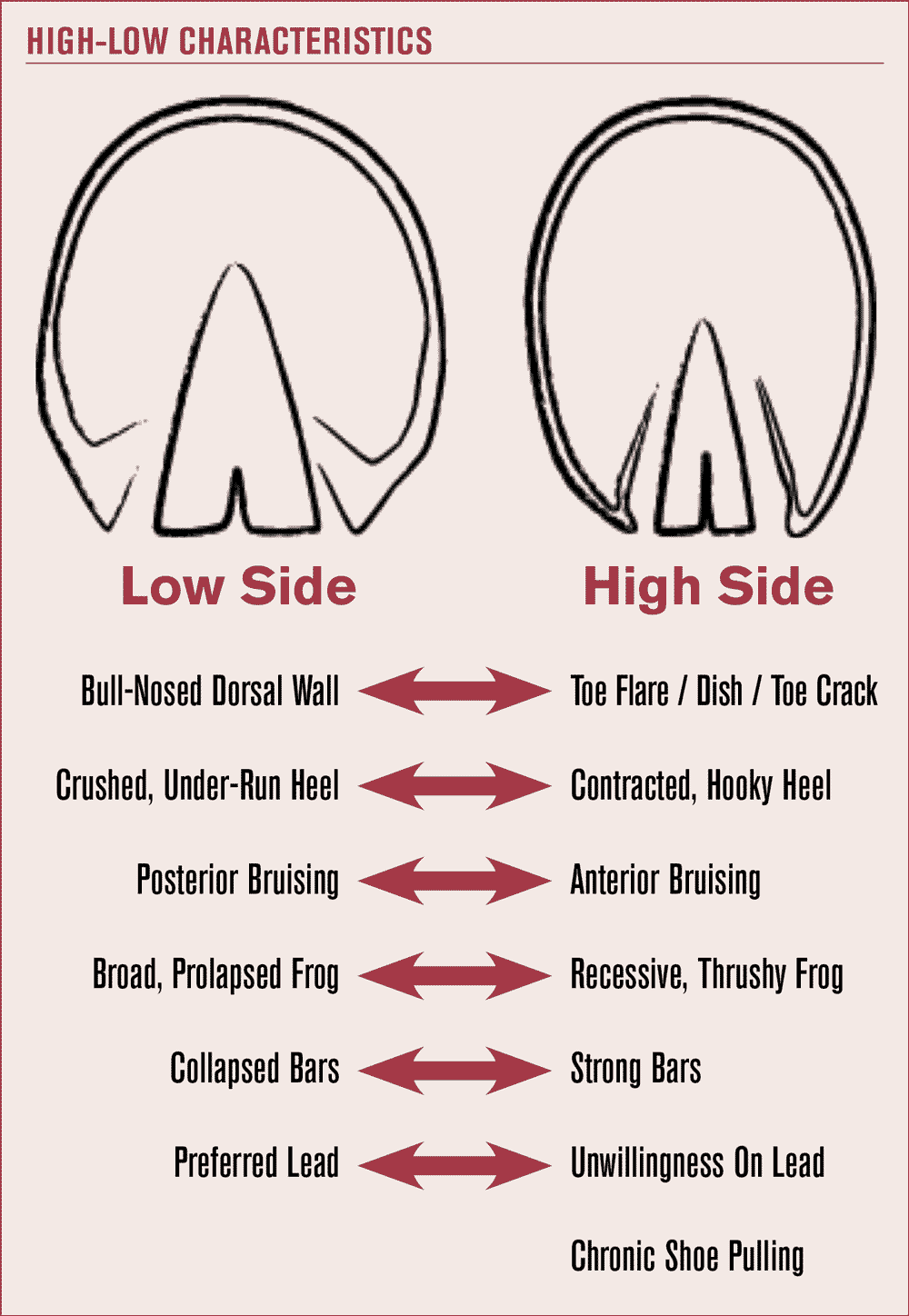

Simply put, high-low feet are disproportionate in that one foot is higher than the other. Since the feet are so dissimilar, each have their own characteristics.

Farrier Takeaways

- High-low feet can be aggravated by how they are worked. When the horse is dominant with one foot, encourage clients to balance the horse’s workload on both the left and right.

- A low foot dominant horse often struggles changing leads to the

high-side foot. - A horse’s trapezius muscles cannot be overdeveloped and bulging like biceps. Rather, it’s likely the result of a postural issue.

- Shoe each foot individually using a systematic hoof mapping approach to help the horse move with suppleness.

- When there is a disparity in a front foot, there will be a diagonal disparity in the hind.

The low foot typically is a broader, more rounded, fuller hoof. Its characteristics might include:

- Bull-nosed dorsal wall.

- Crushed, under-run heel.

- Posterior bruising.

- Broad, prolapsed frog.

- Collapsed bars.

- Preferred lead.

“The horse will often have a broad, bulbous frog,” says the 2018 International Horseshoeing Hall of Fame inductee. “Some people refer to it as a prolapsed frog. In addition to collapsed bars, they will run laterally.”

The low foot typically is also the horse’s preferred or dominant lead, Child says. As a result, when comparing the left with the right, they are almost diametrically opposed feet.

“I find that it runs about 70% that the low side is the left foot and high side is the right,” he says.

The high foot typically is steep and clubby. Its characteristics might include:

- Toe flare, a dish and/or a crack.

- Anterior bruising.

- Contracted, hooky heel.

- Recessive, thrushy frog.

- Chronic shoe pulling.

- Unwillingness on lead.

“You’ll often see a little halo around the coffin bone,” Child says. “It’s a yellowish look to the anterior portion of the foot. I identify that as chronic bruising. It also can have a recessive, thrushy frog in this foot but not the others. The horse will have very little ground contact and usually if they’re going to pull a shoe, they’re going to pull it on the steep foot.”

There is obvious damage on the low foot including crushed, under-run heels. Typically, the low foot is the horse’s preferred or dominant lead.

Both feet tend to take on different appearances, though, depending on whether they are shod. When bare, the heels run forward on the low foot, while they are stacked on the steep foot (Figure 1). The horse also often dubs or breaks off the toe on the steep foot. When shod, farriers often overprotect the foot. Combine that with a longer cycle and the differences become more apparent.

“You’ll get a little bull nosing over the low foot and dishing on the high foot,” Child says. “It’s pretty obvious what happens to the low foot. We see that heel crushed, it’s run up and it takes a lot of stress.”

The damage to the high foot is not as obvious on the outside. Yet, it’s apparent radiographically.

“We see obvious capsular damage on the low foot,” he says. “When we start looking inside the high foot, then we see that we have pedal osteitis issues and it’s torturing the anterior portion of the foot as much as it’s torturing the posterior portion of the other side (Figure 2).”

Damage to the high foot is apparent radiographically. While the low foot damages the posterior portion, the high foot typically damages the anterior.

When a horse with high-low feet is in a static mode, it often takes on a grazing stance in which the low foot is forward and the high foot is back (Figure 3). While some might consider it limb-length disparity, Child doesn’t see it that way. Rather, he views it as loading characteristics and postural adaptation or choice.

Horses with high-low feet often take on a grazing stance when it’s in static mode. They often place the low foot forward and the high foot is back.

“I find the same thing in myself and other people,” Child says. “As I’m standing, I feel like my shoulders are level, but I know from looking in the mirror that I’m actually drooping on one side. I also know that when I’m in a relaxed conversational posture, I will put my left leg forward and my right leg back. If I do the opposite, it makes me nervous and uncomfortable and I’ll switch back.”

A consensus on what causes high-low feet is elusive. Some believe it’s congenital, while others regard it as acquired. It has been attributed to a number of situations including genetics; injury; conditioning; grazing stance; and long-leg, short-neck conformation. Regardless of how it occurs, Child believes that humans have a hand in it.

“I did some casual observations last year at the English barns I work in and almost everyone uses mounting blocks on the left side and went on the left lead away from it,” he says. “Almost everything they did was done from that left side. It’s interesting how much we aggravate these conditions.”

Child tries to encourage his clients to recognize when they are aggravating the condition.

“I talk to them about the fact that they just spent 70% of their longe work going to the left,” he says. “I ask them to help me out by doing something more balanced. However, I’m not going to try to get people start mounting from the offside. You’re not going to change their practices, but I do try to encourage them to recognize what they’re doing.”

Performance Issues

When performing, trainers and riders are looking at rhythm, suppleness, contact/connection, impulsion, straightness and collection. Farriers play a big role in all of those except for contact/connection.

“We get blamed when Daisy pulls off a shoe on a fence, but we don’t get blamed when Daisy can’t make it from second-level dressage work to third level,” Child says. “It’s very important for us to recognize and try to help our clients understand that, no, it’s not our fault when Daisy pulls that shoe off on a fence, but maybe I can do something to help with the straightness issue. In terms of performance, we’re playing on this scale as much as the trainers are.”

With the elements of that scale in mind, one of the biggest performance-related problems associated with high-low feet involves the aforementioned relationship between left front dominance on the low side and the unwillingness to take the lead on the high right side.

“They’ll make a smooth, flowing transition into that left lead and they’ll skip and hop into the right lead,” Child explains. “It becomes a huge issue for dressage when you’re doing tempi changes and there are six lead changes in a row. “

Another concern in dressage is that the high-low horse also loses suppleness on the lead when cantering on the strong side.

“They look like their head goes up a little bit and they seem rougher and choppier,” he says. “They want to fall in on you. They’ll almost fishtail around the corners, like when you skid around a corner on a dirt bike.”

It’s not just a rider-related issue, either.

“You see the same thing on a longe line,” Child says. “When you put the horse on the strong side and they’re out there on the end of that longe, they’re pulling on it and they’re staying out there. When you put them on the weak side — the steep side — they fall in too easy. You have to use the longe whip to keep them going out and going away from you because they’re falling into you on the circle.”

The trapezius muscles are often mistaken as being overdeveloped when it bulges in the withers on the dominant low side. The steep side often appears slaggy and flat.

Muscle Bound

Although it’s not certain whether these performance issues start above the foot or below, one thing is — the horses’ anatomy plays a role simply because it doesn’t have a clavicle. Rather, the horse has a thorasic sling that secures the front limbs in place.

“They don’t have a clavicle to act as a strut,” Child says. “In a human, the collar bone is basically a fuse. It’s designed to break so your shoulder doesn’t. Since the collar bone isn’t there for a horse, it allows for fluid and supplement movement. But it also allows for structural weaknesses.”

There are two main shoulder muscles that are important — the cervical trapezius, where the front of the saddle rests, and the latissimus dorsi, which is behind and below the trapezius. The dominant low side of the cervical trapezius is often mistaken as being overly developed when it bulges in the withers. Meanwhile, the steep side often appears slaggy and flat.

“They’re trapezius muscles and they are flat,” Child says. “They’re not biceps. They are not bulging, bulky muscles. I don’t know that you’re looking at an overdeveloped muscle so much as you’re looking at postural issues.”

Much like Child prefers positioning his hips so his left leg is forward, the high-low horse has what he and Noblesville, Ind., veterinarian Tim Fleck call a scapular disparity.

“It’s postural for me and it’s coming at the pelvis,” Child says. “On a quadraped, it’s coming at the scapula, but if you think about it, they’re basically multi-pelvic animals. They have the true pelvis at the back, but that shoulder and wither area is functioning as a pelvis. So, you have a drive pelvis behind and a support pelvis up front.”

When the horse is in motion, there is a rotation of the scapula. The low side rotates forward and then bulges up.

“There’s an abduction there,” he says. “When the horse swings and strides, it has free motion when it comes forward and achieves extension.”

The high side, though, is just the opposite — it’s adducted.

Horses do not understand the idea of working through pain, they want to work around pain …

“When it comes forward, there’s restriction and horses do not understand the idea of working through pain,” Child says. “They want to work around pain. When the horse hits that restriction, he feels it and raises up the limb. So, you have extension with one limb and elevation with the other.”

Good riders, though, can hide the elevation that occurs in the high side.

“When my wife gets on a horse, she rides completely differently according to what the horse does,” he says. “When she rides a high-low horse, she sits on the low-side lead and that horse is strong and supple. She sits down, drops in and rides it. Then she goes to the high-side lead where it’s choppy and the horse’s head is up a little bit and it wants to fall out and she half seats it. She does it so automatically that she doesn’t even realize she’s doing it, but the horse looks similar going both ways.”

When average riders try to sit down and drive though on the high-side lead, the horse will swap out.

“A high-low horse is like riding two different animals,” Child says. “If you’re riding them as if they’re two different horses, it works.”

Another element to a high-low horse is that it chooses the low side because it can drive harder off of that diagonal.

“There was a time when I was convinced that it was all front end,” he says. “No, it’s front end and hind end.”

Child likens it to the way that a boxer fights — one arm is responsible for jabbing while the other is reserved for power punches. After the boxer’s posture is set to jab, it’s physically impossible to swing for power. The fighter must change his footwork to able to swing for power with the same arm.

“That’s what these horses are doing,” Child says. “They are posturally set up to jab on the high side and to roundhouse on the low side. That set-up drives what they do. As farriers, we’re trying to free up that occlusion that keeps the high-low horse in that sideways position that makes them short on one side and longer on the other.”

Where the horse is in its shoeing cycle can have a profound influence on the shoulder level. As a result, Child suggests that the farrier, body workers, veterinarian and even the saddle fitter communicate.

“These horses make saddle firms lots of money,” he says. “They’re wonderful for body workers because they don’t stay the same when I shoe a horse. That shoulder level will change. During the course of the cycle, those muscles go back to where they were. If the saddle fitter shows up at the beginning of the cycle, there’s a minor adjustment. If the saddle fitter shows up at the end of the cycle, there’s a major adjustment. These horses need a team to maintain them properly.”

Shoeing and Trimming

Child’s approach to trimming and shoeing has significantly evolved since he started shoeing in the 1970s. Like many farriers, he was taught to match feet, make the angles 55 degrees and perimeter fit the shoe.

“To do that with a pair of mismatched asymmetrical feet, I have to make the big foot smaller or make the small one bigger — and I still have to maintain my perimeter fit,” Child recalls. “In some cases, because I was doing a lot of long-footed horses when I started out, I used acrylics and fillers to make them look like they matched.”

As he moved along in his shoeing career, Child started wedging the low foot to match the angles.

“I still do that on occasion, depending on the horse,” he says. “Wedging the low foot and making it more normal was the only thing that I knew to do. The weather environments that I started working in said, ‘No, you can’t get away with that.’ I simply crushed the heels further.”

Now, rather than match mismatched feet, Child shoes each foot individually utilizing hoof mapping.

“There are various ways of mapping feet — the center of rotation, Duckett’s dot, Duckett’s bridge, ELPO systems,” he says. “It doesn’t matter what map you use, as long as you have some systematic approach for getting your feet to work together and a map system that allows you to do that. I’m old school, so I tend to use Duckett’s dot and Duckett’s bridge.”

When trimming and shoeing a high-low horse, Child re-emphasizes the importance of recognizing that there are significant differences in the two feet. One foot is narrow and the other is full. The frog on the steep side is recessive and there is a tremendous amount of mass in front of it that’s not present in the low foot.

“The bars on the low-side foot are running laterally and the seat of corn has moved forward,” Child says. “The heels are actually functioning up near the heel quarter instead of back at the buttress of the foot. Whereas, on the high side, there are strong, straight bars that are coming back and running pretty true.”

Child points out that there are two main differences among farriers — one group fits feet, while the other places shoes. When it comes to shoeing high-low horses, Child fits in both categories because he fits one foot and places on the other.

LEARN MORE

Gain more insight from Danvers Child by:

- Listening to an American Farriers Journal Podcast interview with Danvers Child in which he discusses critiquing your footcare work, strategies for better communication and how he approaches high-low hooves.

- Watching the Online Hoof-Care Classroom “The Four Cornerstones of Hoof Health” in which he teams up with

Dr. Lydia Gray to explore the bedrocks of healthy hooves. - Reading “Understanding What You’re Seeing in Shoe Wear,” in which he explains how he identifies and addresses issues shown through shoe wear.

- Reading “Don’t Limit Your Hoof-Care Options,” in which AFJ follows Child on a Shoeing for a Living Day.

Access this content by visiting americanfarriers.com/0719

“To get breakover and proportions right, I have to pull the foot back on the steep side as much as I can,” he says. “It’s so counterintuitive for me. I struggled and fought against it because it’s already a half-a-size smaller. Now I’m saying, ‘I’m going to pull it back and put a smaller shoe on it.’”

Yet, when working on high-low feet, farriers are going to have to get comfortable using different sized shoes. However, there are ways to disguise it.

“I would pull out a number 1 front and a number 1 hind and reshape the hind so they would have the same numbers on them,” Child says. “But I’m still putting on a smaller shoe and I’m still making that adjustment.”

When trimming the heels on the high foot, Child refers to how far back he has placed breakover.

“When I set the 50/50 ratio while using Duckett’s dot, and I bring the shoe back ¼ inch, I can take another ¼ inch of heel off without bringing that horse up and raising him at the heels,” he explains. “And, after about two or three cycles, it starts to look a bit more normal.”

It’s important to take into consideration whether the high foot has a dish. Child says that he used to pad the high foot. Now, he recognizes the importance of leaving foot rather than taking it away.

“If we measure the feet before we start, we’ll usually find that is a shorter foot at the very beginning because we have to work around the dish to get our measurement,” he says. “It’ll be 1/8 inch to ¼ inch shorter already before you ever do anything to the foot. Then it has more concavity in it, so it encourages us to trim it more from the bottom. All of a sudden, we’ve exaggerated something that was already a problem. You have to take that dish into consideration and work with it.”

Child often is able to go up a little in shoe size because the horse is starting to utilize the high foot.

“When the horse starts using that steep side, it’s no longer torturing the low side,” he says. “The horse is designed to be heavy on the forehand. It’s the reason it doesn’t look like a tyrannosaurus rex. The more we can get them to utilize that steep side, balance their weight and be more symmetrical, the less they’re getting tortured on the low side. And, so I get it set back, the horse starts taking stress off of that low side and we get recovery in the caudal aspect of the low foot.”

Horses work on diagonals, so when there’s a disparity in the right front, there will be a diagonal disparity in the left hind — although, it might not be as obvious.

“It’s not going to jump out to you as much, but the same adjustments that you’re making in the front, you’ve got to make diagonally and behind,” Child says. “When you start measuring and evaluating these horses, you’ll see that your breakover has run forward. Your heels are a little crushed on that diagonal hind. So, you can’t forget to pay attention to the hinds.”

Post a comment

Report Abusive Comment