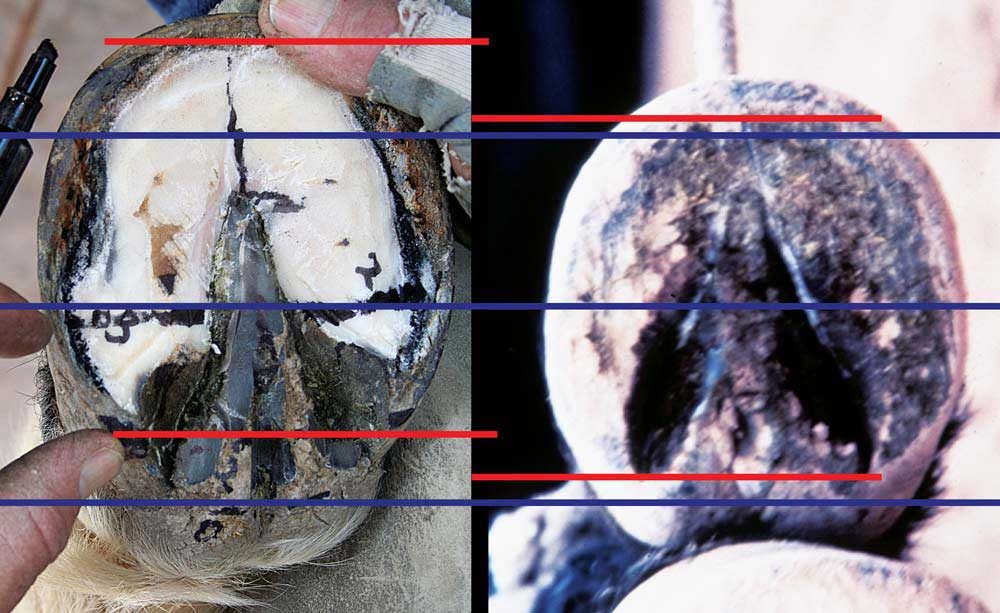

Pictured Above: Conventional foot mapping (represented by the blue lines) shows that much more of the foot on a lame horse (left) will stretch beyond the front line than on the healthy foot (right), which features the reduced surface area advocated by Gene Ovnicek.

The following article is based on Gene Ovnicek's presentation at the 2019 International Hoof-Care Summit. To watch the presentation, click here.

Drawing on 60 years of experience, master farrier Gene Ovnicek says he and other horseshoers are finally reaching a point where they can help prevent lameness with advanced hoof mapping, reduced ground surface and his newest development, the Freedom Shoe.

Ovnicek has been studying shoeing techniques for decades, which led him to establish Equine Digit Support System (EDSS), a manufacturer of hoof-care products in Penrose, Colo.

The Freedom Shoe uses a solid piece to cover the entire sole and provides leverage appropriate for supporting the internal structures of the foot, Ovnicek says.

Farrier Takeaways

- Conventional foot preparation can misrepresent the optimal placement of the P3 relative to the hoof wall.

- Forget “the bigger the foot, the better.” Reduced ground surface area can benefit many lameness cases.

- Many lame horses can return to performing at a high level.

“But the most important thing is hoof preparation,” he stresses, “because it is the key to preventing lameness and resolving some of the issues we’re confronted with.”

He recalls that foot mapping started simply with other farrier researchers. Early mapping called for drawing a line across the sole at an approximation of the location of the foot’s internal structures.

“The idea was to divide the foot equally from front to back around that line,” he says. “At least it helped me understand the references they were trying to portray on the bottom of the foot.”

After adopting the basic mapping approach, Ovnicek eventually compared the foot of a healthy horse to one of a lame horse.

“It became apparent that once I drew the line there was a discrepancy between the two feet,” he says. “The lame horse had more in front of the line than behind.”

Rethinking Foot Mapping

Ovnicek worked with a veterinarian to take radiographs and reconsider the widely accepted belief about the orientation of the coffin bone within the hoof capsule.

“I was taught that it maintained its relationship to the dorsal wall, but we found out that it doesn’t,” he says.

“That was a game changer for a lot of people,” he says because it meant conventional foot preparation might be creating hoof leverage that contributed to lameness.

The Equine Lameness Prevention Organization (ELPO) conducted a hoof mapping study with more than 100 hooves.

“We exfoliated the feet, found the references that we thought would be consistent with the internal structures, then put static markers in,” he says.

The study pointed to a spot 1 inch back from the apex of the frog, where the bars terminate, at the widest arc of the foot, and seemed to have a 90% or better correlation with the center of rotation of the coffin joint.

“But more importantly, it gave us an accurate reference to where the tip of P3 was,” Ovnicek says. “That information could be used by anybody in the industry to prepare the foot. It meant trimming the heels to a given spot. It meant putting the shoe in a given spot to reduce distortions in the foot, at least to a point where you could put on a shoe that would be acceptable.”

Evolving Shoe Designs

Before the ELPO mapping study, Ovnicek and others established some basic mapping guidelines in the early 1990s. Those guidelines led him to experiment by modifying the toes and heels of shoes with the goal of finding a better fit to reduce the stress on the internal structures. Farriers in different areas for at least three successive shoeings tried each modification on 25 to 30 horses at a time.

The modifications eventually led to the development of what Ovnicek called the Natural Balance shoe, a therapeutic shoeing system that included P3 protection and reduced leverage by way of a breakover point back toward the inner rim of the toe.

Although he found it helped eliminate foot distortions, acceptance of the Natural Balance shoe and its unusual placement on the foot “didn’t come without some resistance,” he concedes.

“Setting a shoe behind the white line was not a popular thing in the industry,” he says, “and we took a lot of flak for that.”

The evolution continued, with EDSS introducing the center-fit shoe featuring hash marks to help farriers properly locate the shoe on the foot.

“The same thing was true with the PLR (Performance Leverage Reduction), which has become a very popular performance shoe,” Ovnicek says. “It’s light and has reduced edges for horses that turn corners. We had discovered that that’s important in preventing lameness.”

Along the way, Ovnicek noted how sensitive horses were to simple design changes.

“It became even more important as we looked at the aluminum shoes that we used that had no wear plate in them,” he says.

As the shoe wore back, the horses with lameness issues tended to get better.

“That gave us a whole new direction on what we thought was important and how leverage played a role in lameness,” he says.

The Freedom Shoe features reduced edges and three basic points of transition, which Ovnicek calls release points within a relationship to the center of rotation of the distal interphalangeal joint.

Focusing on Leverage

Hoof anatomy indicates that horses are not entirely designed to turn corners in the way we ask them to today, Ovnicek says. The lamenesses that are incurred as a result are basically soft tissue lesions long before they become arthritic. He found that performance horses that routinely turned corners were often lame going one direction but not the other.

So Ovnicek developed a static leverage testing system meant to simulate a lameness exam. The test also simulated turning corners by raising the front, back and sides of the hoof.

“Most horses, depending on the severity of the lameness, seemed to not want to lift their foot up,” Ovnicek says. “If you did get it up, they’d put it down quickly. But if you moved the leverage to the other side, most of the time they would have their foot off the ground before you could ask for it.”

He tested 100 horses, putting a rail or elevation on the inside.

Ovnicek says the height of the rail played an intricate role in the healing process, and most horses wore a lift on the inside no longer than they needed it. However, he adds, a few of his test horses continue to wear an inner rail.

“We don’t know what’s wrong with them,” Ovnicek says, “but they just don’t stay as sound unless you have something on to help with their comfort level.”

Continuing with leverage testing, Ovnicek tried reducing the ground surface area on the lateral side instead of lifting the inside.

“The secret was to reduce the ground surface area on the lateral side to make it easier to turn,” he says. “Amazingly enough, the horses that had some lameness issues started to perform better.

“That opened the door to a whole new generation of treating lameness. It had always been believed that the horse needs a bigger ground surface area. The bigger the foot, the better the support. That’s not true. I can show you horses that perform at the highest level that have a very small ground surface area.”

The Freedom Shoe

Ovnicek notes that there was a limit on how much the outer edge of the shoe could be brought in. So a clog was later used because it could be ground in as far as needed for a particular horse, he says. A small wear strip could also be added to the bottom and moved around as needed on severely lame cases.

The Freedom Shoe features a landing surface with reduced edges and three basic points of transition, which Ovnicek calls release points, “all within a close relationship to the center of rotation of the distal interphalangeal joint.”

“We like to think that injuries that have occurred to those areas — the collateral ligaments, the deep flexor and the surrounding connective tissues of the joint — get to release when the horse starts to move in a given direction,” he says.

There’s always a concern when you cover up a foot, Ovnicek says.

“How does the foot respond to it?” he says. “I’ve had horses in clogs for over 5 years. The foot just keeps getting better as long as I maintain the environment under the clog. Three sessions with the Freedom Shoe and their foot seems to respond. We’re able to control the variables of distortion.”

He says it’s imperative to place hoof packing between the shoe and the sole. He has used a variety of products to disinfect and protect the foot, including Artimud, Magic Cushion and oakum.

Over a period of about 4 years, Ovnicek says, “We realized that the reduced ground surface was really helping a lot of horses. A lot of these horses went to high-level performance on a clog with a strip on it or a Freedom Shoe prototype.

“The results have been extraordinary. Not every horse gets as sound as I would like, but there’s an overwhelming number that become sound.”

Ovnicek says acceptance of his innovations comes down to “changing your thinking, getting rid of the idea that the bigger the foot, the better. Horses can function perfectly on a smaller ground surface area — and they benefit from it.”

Post a comment

Report Abusive Comment